Refugees wishing to stay in Germany must learn the language and integrate—or risk losing their permanent residency.

“For those who refuse to learn German, for those who refuse to allow their relatives to integrate—for instance women or girls—for those who reject job offers: for them, there cannot be an permanent residence permit after three years,” German interior minister Thomas de Maizierede told ARD television (link in German).

In August last year, at the height of Europe’s refugee crisis, Germany became the first European country to free Syrian refugees from a so-called “draconian bureaucratic trap,” which forced them to apply for asylum in the first safe country they landed on. As a result, more than one million refugees registered in Germany in 2015 alone; the country took in more refugees in one year than the US has in the past 10 years.

De Maiziere’s proposed legislation, which will be drawn up in May, will also include a requirement that refugees have a fixed abode. “We don’t want ghettoization,” he said. “We want to regulate it so that recognized refugees — at least as long as they do not have a place of work to support their livelihood — stay in the place where the State decides is right for them and not wherever the refugee feels is the right place.”

But not everyone is a fan of the government’s approach to integration. The German Trade Union Federation (DGB), the biggest trade union organization in the country, has slammed the government for the proposed legislation (link in German). Annelie Buntenbach, board member of DGB said: “Successful integration can’t be achieved by changing laws and adding sanctions and fixed-abode requirements.” Instead, she has called for comprehensive language and integrations courses, and municipalities dedicated to integration.

The Green Party, as well as the Social Democrats (SPD), the junior partners in chancellor Angela Merkel’s coalition government, have also criticized the new plans. Sigmar Gabriel, head of SPD, said the government must (link in German) “encourage integration, not demand it.” SPD vice-head Ralf Stegner echoes Gabriel’s point; he told the newspaper Die Welt (link in German) that the government must work to “integrate refugees, not bully them,” adding, “where there is a lack of free will, there will also be consequences.”

Merkel’s open-door policy toward refugees was in stark contrast to many other countries that shut their doors to those fleeing to Europe. “Germany is doing what is morally and legally obliged,” Merkel said in September (paywall). “Not more, and not less.” Her response to Europe’s refugee crisis earned her Time magazine’s Person of the Year.

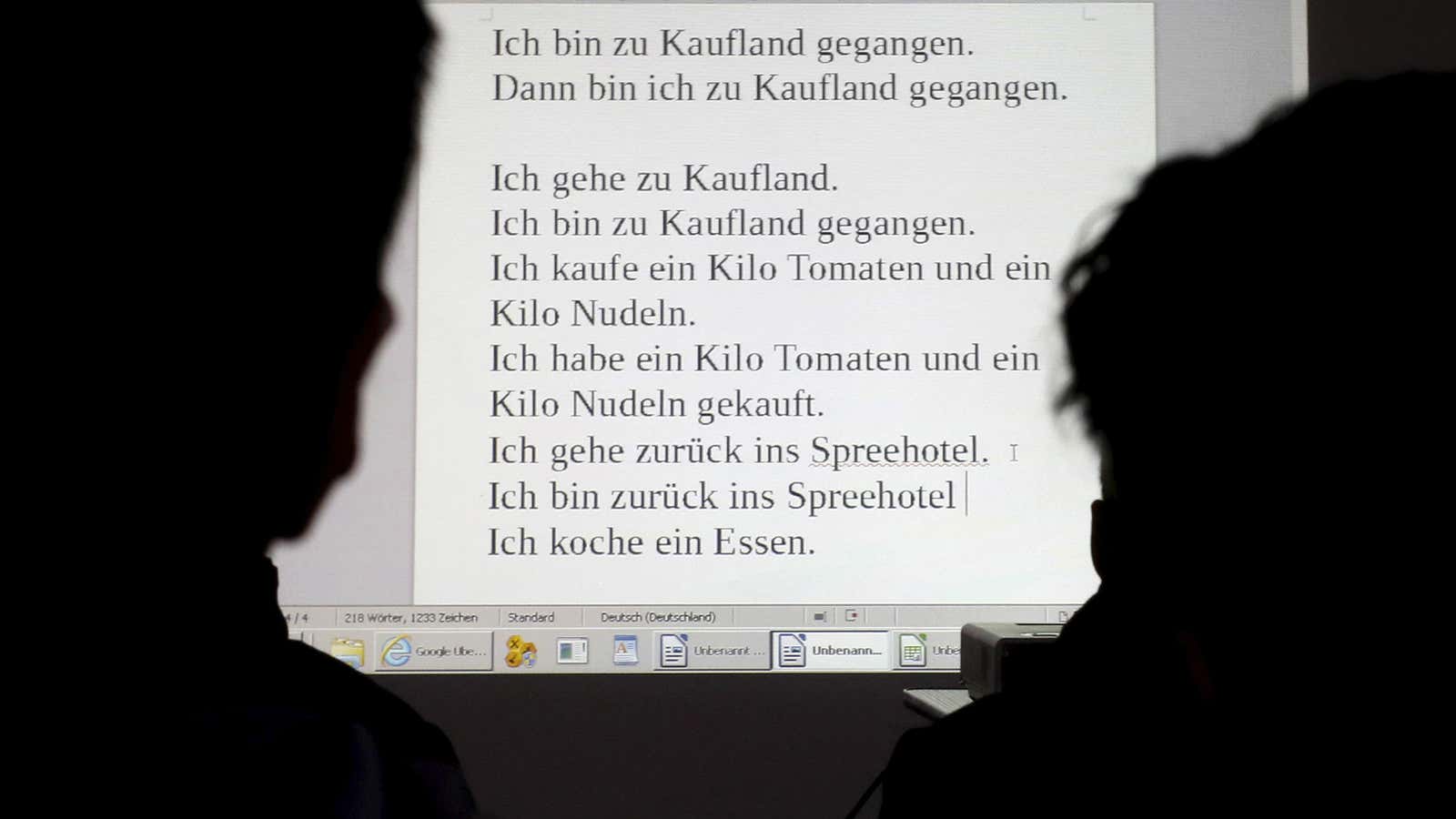

While some may see refugees as a burden, Merkel described the large influx of refugees as an “opportunity for tomorrow.” She’s also emphasized the importance of integration, calling on refugees to “learn German quickly and find work.”

Big business has helped somewhat with the latter, with Deutsche Post and the automaker Daimler working to fast-track migrants into employment. More recently, there were around 200 companies—including pharmaceutical company Bayer—at Berlin’s first refugee job fair. 4,000 refugees registered to attend in hopes of getting a job in their new home.