This article has been corrected.

Markets are cheering the results of Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s first policy meeting. Kuroda, installed by prime minister Shinzo Abe, has convinced the rest of the central bank it is time to launch an aggressive monetary easing program to pull Japan out of decades of recession and deflation.

The BoJ is going to purchase a massive $746 billion worth of bonds a month—double the current rate—to flood the economy with cash. That could help the central bank reach its 2% inflation target, and would be a huge achievement, as Japanese consumer prices have been on a slow and steady crawl downwards since 1997. The central bank also announced plans to temporarily suspend the so-called bank note rule, which kept government bond purchases below the amount of currency in circulation.

Japanese stocks rose almost 1% after Kuroda gave investors much of what they wanted. The yen also fell on the news, which will further boost profits for the country’s exporters.

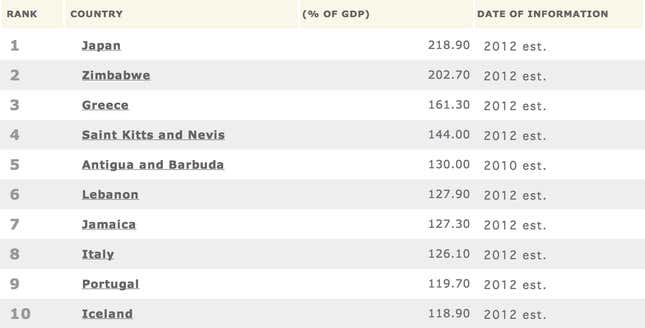

By attempting to spend its way out of recession, however, the BoJ is taking a calculated gamble. Critics of Abenomics point out that if the gamble goes wrong and quantitative easing does not raise prices of goods and services, it could damage Japan’s economy further, adding to the debt load and potentially increasing government—and therefore corporates’—borrowing costs as lenders demand higher interest rates for the increased risk of extending credit to a nation that is even more deeply in hock.

Although traders are cheering the BoJ’s move, it is possible many of them have short memories (or do not read).

Japan tried quantitative easing from 2001-2006 and the experiment did not propel the country back to growth. Its underlying problems were too deep. There is not yet much evidence monetary easing has caused serious cyclical improvements in the American economy either.

For years Japan has been a place that investors get excited about every so often, before realising the economy has too many structural faults to create long term growth.

There is also much more the Japanese government needs to do beyond monetary policy. It could encourage its exporters to shape up and really start to compete with China. It could encourage more female participation in the workforce, and champion entrepreneurial businesses ahead of the army of zombie companies that should have been put to death in the 1990s but are still alive, thanks to low interest rates and the generosity of their bankers.

But for now, monetary policy is the only story investors in Japan want to listen to. That could easily change.

Correction: An earlier version of this article said that Japan would have to borrow to fund its asset purchases, which is an inaccurate description. (The central bank prints money to pay for asset purchases; this does not in itself increase government borrowing.)