Why Abenomics might be nothing more than a buzzword

In the next few months, the market will learn whether new Japanese leader Shinzo Abe’s promise to drag Japan out of nearly two decades of recession and deflation was just a nice story.

In the next few months, the market will learn whether new Japanese leader Shinzo Abe’s promise to drag Japan out of nearly two decades of recession and deflation was just a nice story.

Today marks new Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s first policy meeting at the helm of the Bank of Japan—the institution Abe has tasked with much of the heavy lifting needed to restore Japan’s growth and turn his hopes for inflation into reality.

According to Goldman Sachs, Kuroda has six to 12 months to prove he can meet his target of 2% inflation within two years. Investors expect the central bank to closely copy American Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke in flooding Japan’s economy with new money via asset purchases.

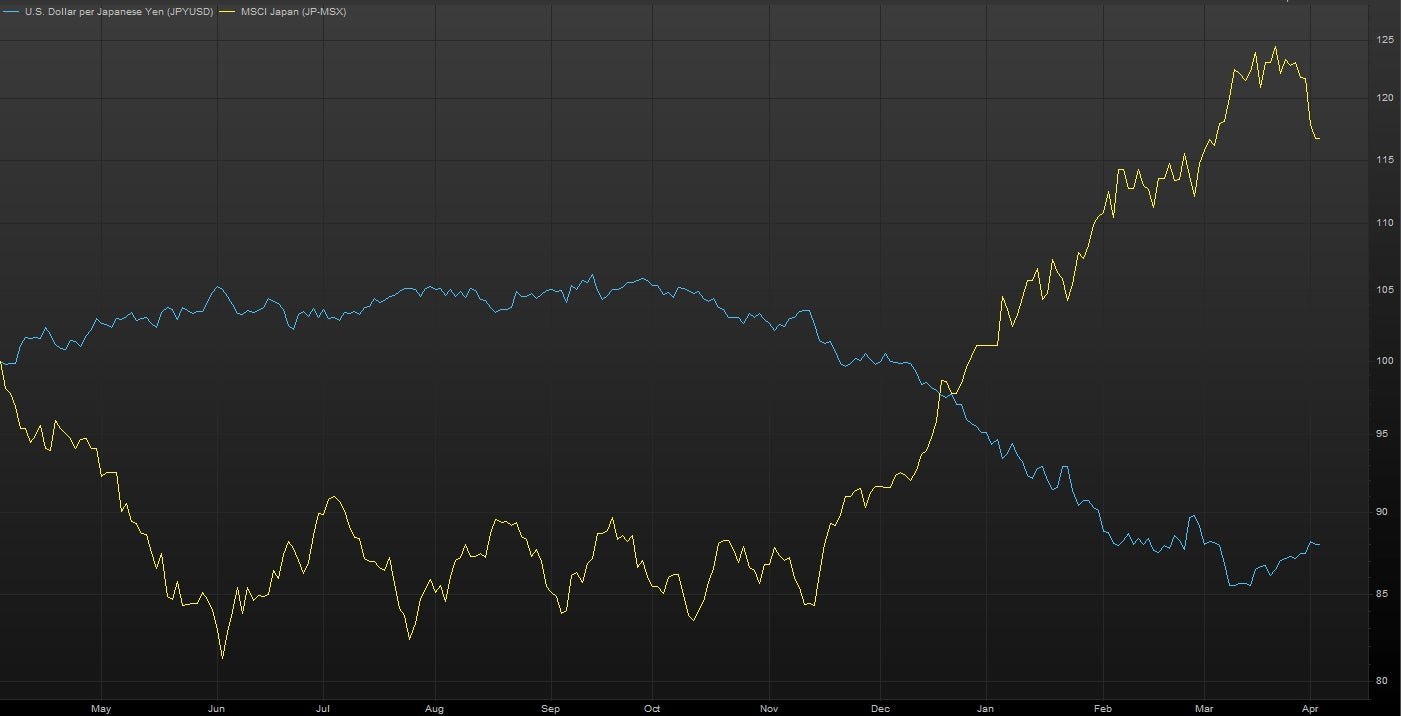

The yen has fallen sharply against the dollar in the last six months on expectations of this monetary easing. And Japanese stocks have risen as investors assume the weaker currency will help the nation’s exporters sell more goods overseas.

That means much of what Kuroda might do next has long been priced into the Nikkei and the yen. Traders are now looking ahead to see whether Abenomics will really solve Japan’s problems. So Kuroda does not have long to act.

Investors already seem bored. Enthusiasm is seeping out of the ”short yen, long Nikkei” trade. The market is now in a “show me” phase, challenging Japan’s leaders to get things done.

This chart shows the inverse relationship between the falling yen and rising stock prices is beginning to falter, with the currency (blue line) rising again as stocks (yellow line) decline.

The chief investment officer of a Hong Kong-based hedge fund, who is still doing the yen-Nikkei trade, admits he has been buying the Abenomics story without believing it.

“Do I think Japan can be cured by monetary policy alone? Of course not. Any idiot can see that,” he told Quartz.

There are myriad reasons why Abenomics might be a duff idea.

One of Abe’s big plans is to boost growth by spending heavily on new infrastructure. That creates the danger of money flowing into unnecessary projects that do not boost economic output. It is also a page out of an old playbook. Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party has leaned heavily on building new roads and bridges during previous terms in power. The result was mainly to increase the nation’s debt.

And while the prospect of monetary easing has spurred traders to drive down the value of the yen, the weak currency does not change Japanese companies’ long-term growth prospects. It has given Japan’s previously struggling exporters an artificial boost. And that may cause the sort of complacency that stops Japanese carmakers from addressing strategy missteps they have made in China and dissuades electronics firms from making tough decisions to lose staff and relocate to cheaper markets.

Japan faces myriad other obstacles to economic growth that a central banker alone cannot solve. As Bloomberg columnist William Pesek writes here, deflation is a “symptom of what ails Japan.” Pesek suggests these plans for recovery: ”tax reform, deregulation, joining free-trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, empowering women, supporting entrepreneurs and increasing productivity.” Abe does not seem to be addressing such issues.

Meanwhile, the monetary easing Abe has promoted has been tried before in Japan. It failed to spur growth. The nation kicked off a five-year round of what Americans would now recognise as quantitative easing in 2001. This paper (pdf), written by just-departed Bank of Japan governor and staunch Abenomics critic Masaaki Shirakawa in 2002, found that a year of money printing had not done much at all. He wrote: “[The] monetary base grew by almost 30 percent, year on year, as of March 2002. Despite this, nominal GDP growth continues to be negative and economic activity remains stagnant.”

Between 2001 and 2006, Tokyo policymakers also hoped monetary easing would boost growth by stimulating bank lending. But according to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, this did not happen. Instead, Japan’s weakest banks simply found it easier to raise capital, and stayed in business perhaps longer than they should have.

There is also not much proof that the US government’s quantitative easing policy, which began in 2009 has given rise to meaningful, cyclical recovery (though it has been good for the housing market).

Shinzo Abe, meanwhile, seems to have been preparing his excuses, should his economic plan fail. Just before Kuroda’s first central bank board meeting, Abe commented that Japan may not be able to reach the 2% inflation target after all. The culprit for his policies not working, he said, would be changes in the global economy (such macro events, of course, are far beyond any national leader’s control). That sounds like a leader who has made a big promise he suspects he may need to back out of.