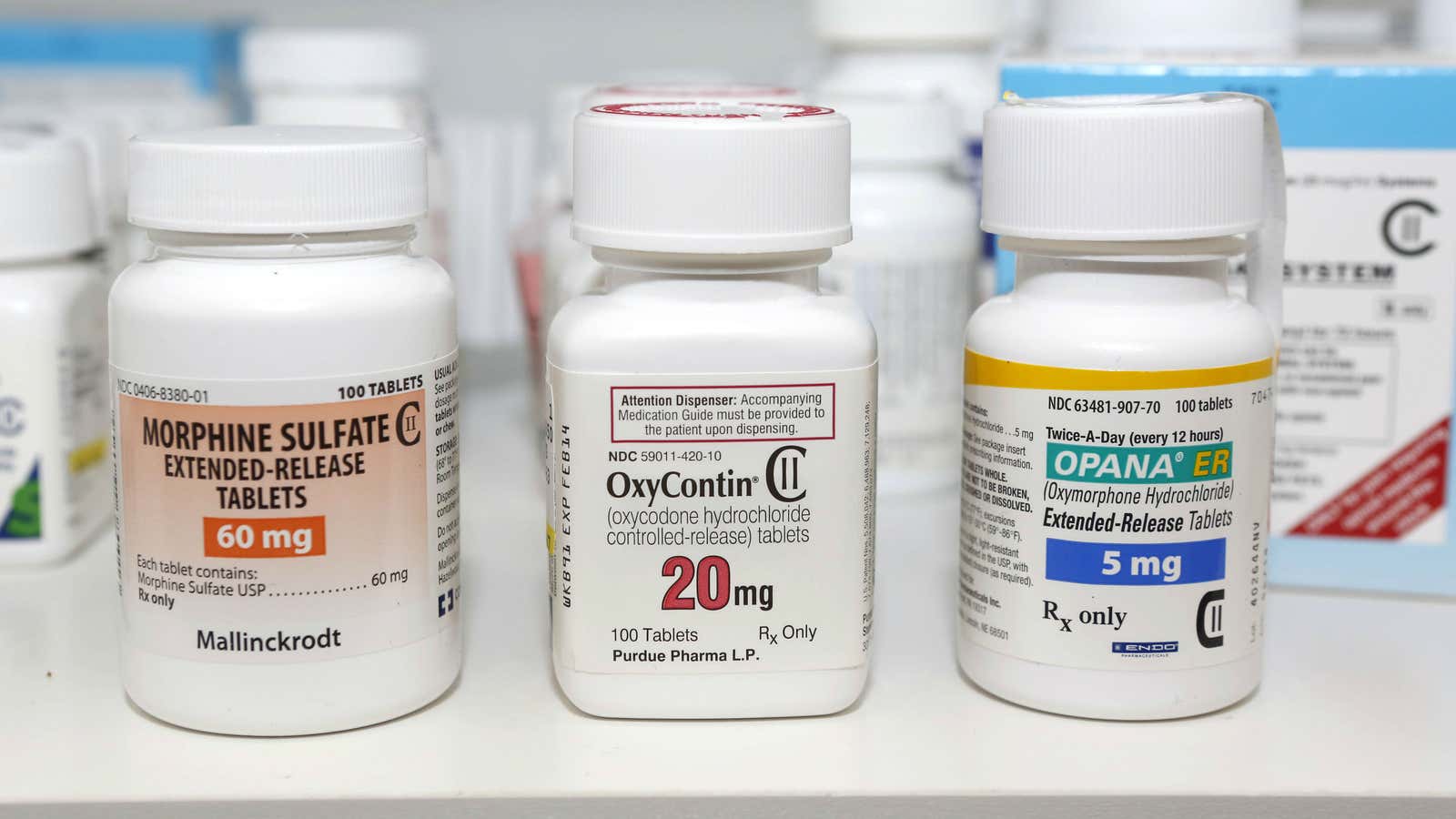

Opioid painkillers—including drugs like fentanyl, morphine and oxycontin—are highly addictive and can lead to fatal overdoses. In the United States, opioid drug abuse has been steadily on the rise, killing close to 19,000 in 2014 (pdf) and claiming the life of the pop-star Prince earlier this year.

The US Centers for Disease Control has begun to recommend that doctors make concerted efforts to prescribe these kinds of painkillers less to help combat addiction, but there isn’t really any current alternative to help those patients that suffer from severe pain.

Today (August 17), scientists from several institutions including Stanford University Medical School and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Medical School revealed that they have identified a compound that appears to work as a painkiller similar to morphine, but without the same affinity for addiction. Their work was published (paywall) in Nature.

Usually when opiate substances bind to opioid receptors, which are found all over the body, they dampen the feeling of pain, produce a calming effect, and flood the brain with chemical called dopamine. This dopamine triggers the brain’s reward system. Over time, the body can become accustomed to having higher levels of dopamine, and requires more of the same drug to generate the same high. In high enough doses, though, these drugs can slow down breathing—sometimes to fatal effect.

Researchers designed a compound, called PZM21, that appears to mimic the pain-suppressing qualities of existing opioid drugs without also causing a surge of dopamine. “PZM21 didn’t produce hyperactivity, which would indicate activation of the dopamine systems,” Peter Gmeiner, a pharmacologist at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany and co-author of the paper, wrote in an email. Another test, he said, showed that mice didn’t have a preference for returning to the same place the drug was administered. Additionally, mice given this compound didn’t show signs of constipation, which is a frequent problem with opioid painkillers.

The researchers created this compound by studying the structure of opioid receptors themselves. “They were able to use the crystal structure of the opioid receptor to design and speed up the development of a drug that has biased signaling, meaning it has a greater likelihood of the desired effect without the undesired side effects,” said Laurie Nadler, chief of the neuropharmacology program at the National Institutes of Mental Health, which partially funded the research.

PZM21 has a long way to go before it can serve as an alternative, less-addictive painkiller in hospitals. Mice, after all, are not humans; the synthetic compound may not have the same efficacy in our bodies. But, this preliminary research suggests that there’s promise in designing drugs with fewer side effects based on how the shape of the body’s receptors for them. “From this animal work, they believe that this compound will be less addictive, but that remains to be seen in clinical studies,” Nadler said.