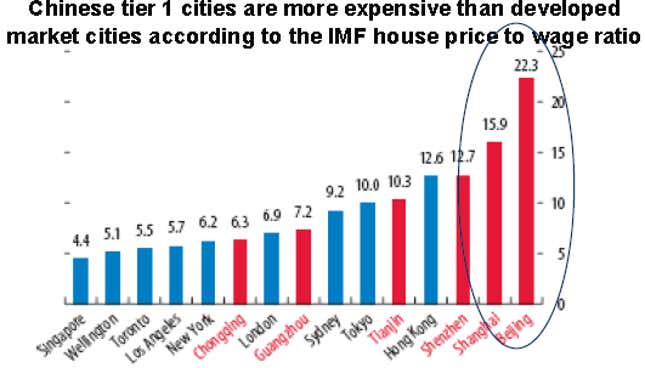

Five big Chinese cities rank among the priciest housing markets in the world, surpassing notoriously expensive cities like Tokyo, London and New York, based on calculations by the International Monetary Fund. In fact, seven out of 10 of the world’s least affordable markets—Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Tianjin, Guangzhou and Chongqing—are now in China. Here’s a look at how China’s biggest cities stack up, via Sober Look:

Note that that the price-to-wage ratio, which measures median housing prices in a given city against median disposable incomes, reflects affordability rather than absolute property value. This means the mid-range price of an apartment in New York is 6.2 times more than what a typical family makes in a year. By comparison, it would take nearly a quarter-century of earnings to buy a pad in Beijing’s capital outright.

Residential property is a big mess for the Chinese government—and it’s not going away. Last month, prices on new homes leapt 7.4% in June 2012—the biggest uptick since last December.

In short, policies to curb housing inflation aren’t working. That’s worrying news for the government; housing prices are a major source of public resentment. The danger isn’t just the threat of popular unrest, though: It’s that soaring property prices make people feel less wealthy and less inclined to consume. And that’s exactly what the government needs them to do in order to wean the economy off its dependency on exports and credit-driven investment.

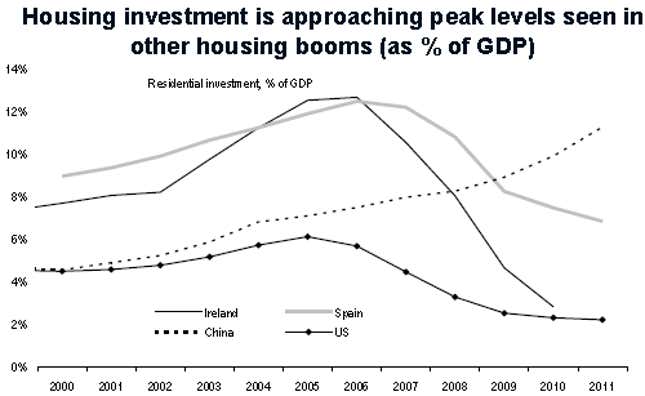

That brings us to the central government’s dilemma: Property investment fuels a big chunk of China’s GDP. Here’s a look at that, also via Sober Look:

Sure, the announcement over the weekend that the government will stop evaluating party officials solely on the basis of their contribution to growing GDP—China’s probably the only country in the world to announce GDP targets as a matter of policy—is truly momentous. If they’re off the hook for hitting targets, it means that local government cadres have less of an incentive to shunt investment to shady property deals to prop up their numbers. It also could make them less reliant on land parcel sales—the prices of which have been rising—to fund their budgets. Part of China’s sky-high housing prices comes from this dependency, as we’ve highlighted in the past. That’s both driven up prices and encouraged over-investment in the sector via shadow lending. But the government still needs something to drive its economy while it waits for its households to start consuming.

Finally, a tanking housing market would probably leave dozens of developers—and their local government confederates—underwater. That could be cataclysmic for Chinese banks that have lent willy-nilly to to developers.

In other words, a drop-off in property investment could cause a big drop in GDP growth, just as cooling the market risks causing a spike in bad debt. Will these costs be more than the central government is willing to risk?