Argentina has a history of inventing strange financial instruments to boost its problematic currency.

The latest example is a little green piece of paper known as a Certificate of Deposit for Investment, or Cedin for short. Essentially, it’s like a gun amnesty, only instead of giving up your illegal guns, you give up your illegal dollars. The Cedin, which the Argentine government began selling on July 1, allows anyone sitting on a pile of undeclared US dollars to trade them in for a certificate slip (pictured below) backed by Argentina’s central bank. Holding undeclared US dollars or using them for purchases has effectively been illegal in Argentina since 2011, when Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner began clamping down on dollar usage as a way to temper inflation.

The Cedin is the first of two bond offerings meant to encourage investment in some of Argentina’s hardest hit sectors (the second will be offered on July 17). Cedins are designed for real-estate purchases; those who exchange US dollars for them can use the instrument to buy homes.

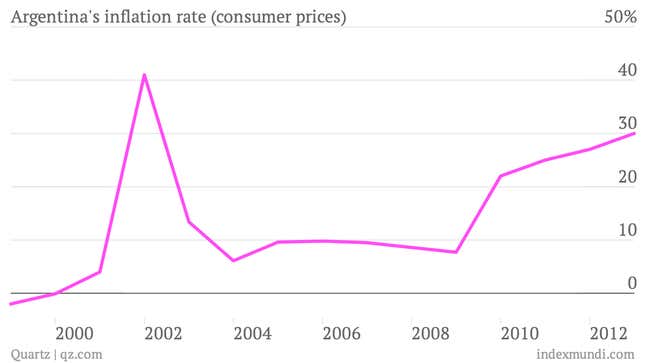

As inflation has risen and people have lost trust in the country’s financial system, Argentines have hoarded US dollars, which aren’t tied to Argentina’s financial woes. The Cedin is the latest of some 30 measures Kirchner’s government has instituted to restrict access to foreign currency; up to now they have only backfired and encouraged more dollar hoarding.

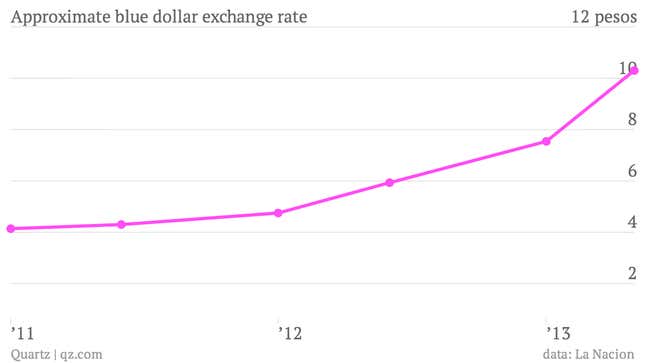

In May, the black market exchange for US dollars in Argentina (which is referred to as the “blue dollar” rate) passed the 10 to 1 mark, double the official exchange rate, which has hovered around 5 to 1. And Argentines now sit on some $160 billion in illegal dollars.

Argentina’s foreign-exchange reserves, which its central bank uses to trade with other countries’ central banks and back its liabilities, have been falling precipitously in recent years. The central bank lost $2.84 billion, or nearly 7% of its foreign exchange reserves, in the first quarter of 2013 alone.

If all this seems like a government plot to boost reserves by eliciting illegal dollars, it is. In May, when the issuance of Cedins was announced, economy minister Hernán Lorenzino explained that he hoped “those who have undeclared savings in dollars” could invest them in “transparent and legal instruments” that will both protect those savings and use them to support Argentina’s real estate sector.

A good chunk of those undeclared savings are probably in the hands of the country’s money launderers. As we pointed out in May, organized crime, drug trafficking and illicit trading are rampant in the region, and Argentina has been scolded by inter-governmental bodies like the Financial Action Task Force for not adhering to international anti-money laundering standards. “They’re taking a chance that these Cedin bonds are going to in effect launder illegal money—money of criminal syndicates,” Dr. Robert Shapiro, co-founder of economic and political advisory firm Sonecon, tells Quartz.

The government is hoping the Cedin will become so popular that it trades “like a quasi-currency,” former general manager of the central bank Hernán Lacunza told Bloomberg. Uruguayan news outlets are already calling the Cedins Argentina’s “second currency” (Spanish link).

But few analysts believe that the Cedin will convince regular Argentines to give up their precious dollars, since buying it amounts to a bet in favor of the Argentine economy. The likeliest buyers will be Argentine money launderers, since their president just gave them a legal avenue for offloading their dirty cash.