Earlier this spring, my husband and I had what I’d modestly describe as a triumph of a dinner party.

Several friends who’d never met one another—some couples, some not—gathered around our table and feasted, laughed, and drank. I have only one photograph of the party: Our friend Danny stood on his chair to snap the tabletop, just before we tucked into lamb chops, tzatziki, spanakopita, and copious quantities of wine.

The photo doesn’t tell me anything about who sat around the table, what made us laugh, or who stayed late, chatting in the kitchen while we loaded the dishwasher. And I’m glad that we weren’t brandishing our phones all night. But that doesn’t mean I don’t want to remember those details, and for this, I’ve discovered a great new app.

Just kidding, it’s actually just a notebook and a pen: a dinner party diary. The day after the party, in this notebook, I wrote down the date, guest list, what we ate, and what the weather was like—I guess because the menu seemed particularly well-suited for a rainy spring day.

I wish I’d jotted down a little more. I cannot, it turns out, remember what made us laugh so hard at dinner. But it was a good start to a new practice. We’re still newly married and, as New York-to-Los Angeles transplants, blissed out by having ample space to entertain.

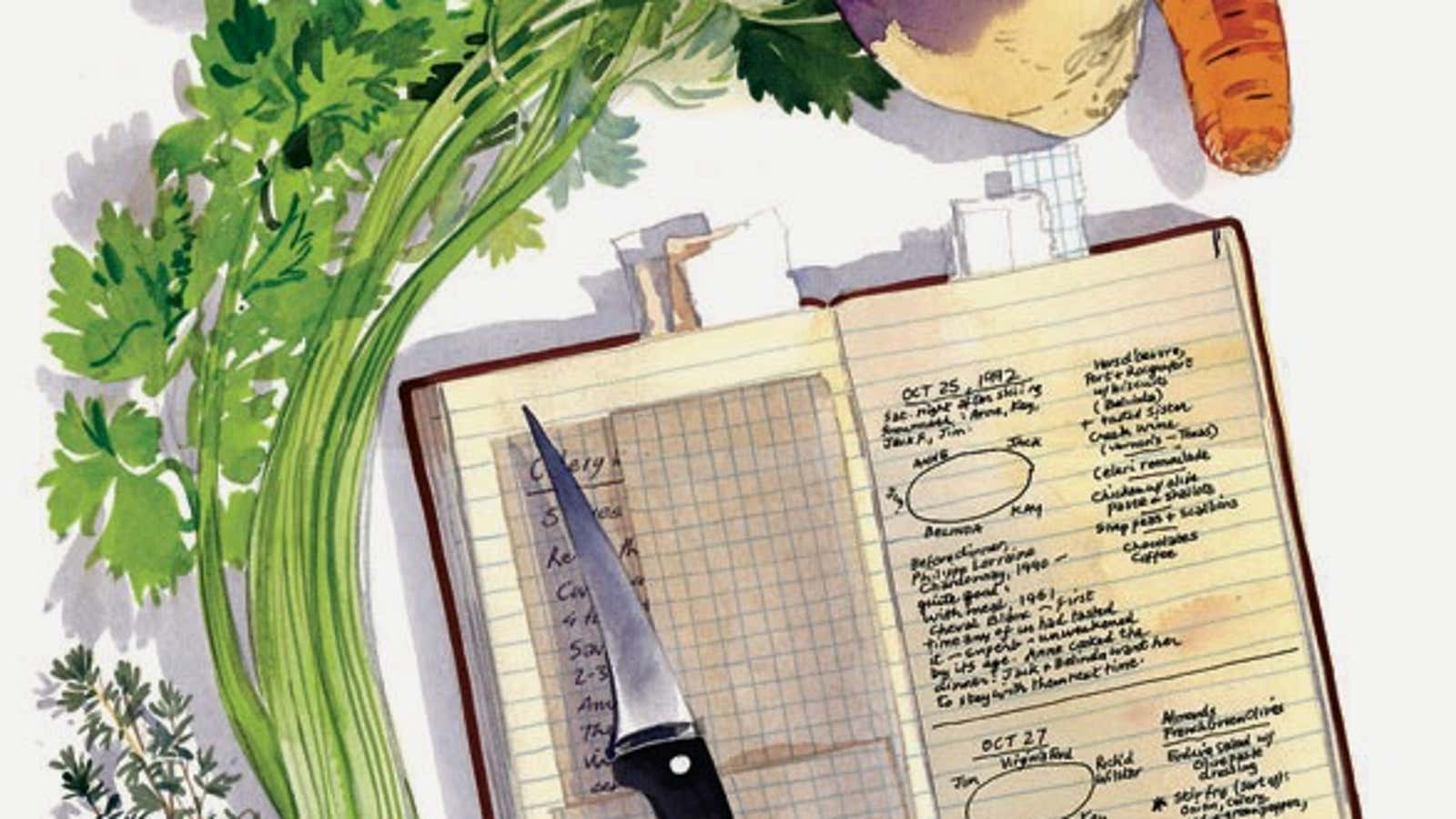

The dinner party diary idea was not my own. It came from James Salter and Kay Eldredge, two writers who kept their own dinner party diary—or the “dinner book,” as they called it—in the 1970s, when they too were newly married and living in Aspen, Colorado, a funky little town back then. Begun in “an old brown notebook,” it eventually evolved into something else entirely: a compendium called Life Is Meals: A Food Lover’s Book of Days, published by Knopf in 2006.

For each day of the year, Life Is Meals provides a morsel of meal-related knowledge—a historical reference, a recipe, a memory, a poem. Life Is Meals’ entries include an adaptation of Marcella Hazan’s polpettone alla Toscana (also known as meatloaf), a very brief history of raising one’s glass in a toast, and a smattering of facts about taste buds.

Salter, an acclaimed novelist, was eulogized as a “writer’s writer” by the New York Times when he died at age 90 in 2015. Eldredge has written short stories, plays, and documentary films. Among their dinner guests were John Irving, who called ahead to say he was in love and ask if he could bring someone (Janet Turnbull Blunt, who has now been his wife for more than two decades), and the legendary New York Times restaurant critic Craig Claiborne, who was delighted by a simple soup of Brussels sprouts, carrots, and chicken stock.

But the book’s most delectable pages are those that feel taken from Salter and Eldredge’s own personal dinner book, with lessons and gossip from these generous hosts. (The July 24 entry entitled “Greek Boyfriend” is a particular favorite.)

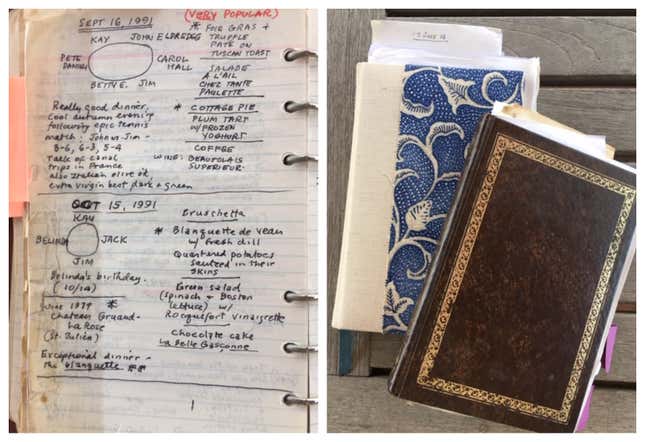

The intention of their original dinner book, Eldredge told me recently by phone, was never publication. It was simply to keep track of what dishes the couple had served to whom in their early days of cooking, when the list of recipes they were comfortable with was relatively small. They kept the record as a practical matter, to make sure they didn’t serve the same meals to the same guests repeatedly.

“That was the beginning of the dinner book,” Eldredge told me. “Jim, who had fabulous penmanship, started keeping a record of what we had served, and who came, and where they sat … He drew a little diagram of the table.”

Eventually it grew more elaborate. The couple would typically clean up together when the guests had gone, and “sort of debrief as we were putting food away or doing dishes or whatever.” The next day James would write it up—nothing fancy, just a page or two. But in addition to the basics, the entry might include tidbits such as who fell asleep in the woodpile, pronounced a roast inedible, or didn’t get along as well as hoped. (For this they kept a list called “Never Together.”)

These weren’t grand or ostentatious affairs, Eldredge told me. They kept the preparation manageable and the guest lists intimate, partly because they lived in a small house. “Our goal wasn’t to be dazzling,” Eldredge said. “We knew people who could be dazzling, and we were going to leave that to them.”

Instead, she said, “Our idea was it was more important for people to have a good time. A memorable time.”

The documentation of these evenings took on a life of its own. “The notebook ran out of pages. There was another and then a third. They became a kind of archive, stories otherwise forgotten, couples that had parted, familiar names, others hard to place,” they wrote in the introduction to their book. “At breakfast—tea and oranges for a period, as in Leonard Cohen’s beautiful song—we read aloud to one another and often leafed through cookbooks, deciding what to make for a party or simply at the end of the day. Life never felt richer.”