Why US congresspeople want to feed sharks to the children

Fairly or not, when it comes to sharks, most people associate them with the “eaters” more than the “eaten.” Not Europeans. And the meat of one type of shark, the Atlantic spiny dogfish, is a particular favorite. It’s used in fish and chips in the UK, where it’s been rebranded as “rock salmon.” Germans know dogfish as “sea eel,” and it’s called saumonette (little salmon) in French and, vitello di mare, or “sea veal,” in Italy. In fact, Europeans in the past have dug dogfish so much that they long ago depleted their own spiny dogfish populations. That’s made it a promising market for US fishermen.

Fairly or not, when it comes to sharks, most people associate them with the “eaters” more than the “eaten.” Not Europeans. And the meat of one type of shark, the Atlantic spiny dogfish, is a particular favorite. It’s used in fish and chips in the UK, where it’s been rebranded as “rock salmon.” Germans know dogfish as “sea eel,” and it’s called saumonette (little salmon) in French and, vitello di mare, or “sea veal,” in Italy. In fact, Europeans in the past have dug dogfish so much that they long ago depleted their own spiny dogfish populations. That’s made it a promising market for US fishermen.

And they sure need it. Americans generally won’t touch the stuff. Long ago, US regulators stamped out American attempts to rebrand dogfish as “steakfish” and “grayfish,” though it’s sometimes now marketed as “cape shark.”

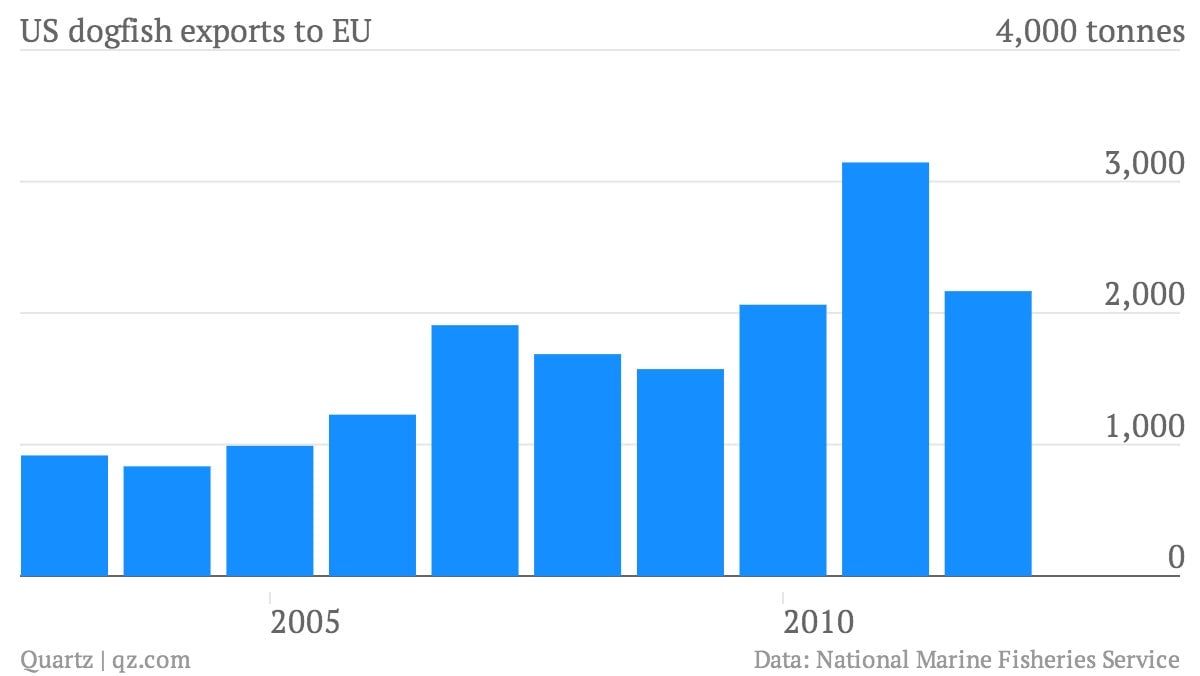

Now there’s a new problem, though. The recession across the Atlantic has caused Europeans to cut back on their veal-of-the-sea habit. Here’s a look at US export trends:

That’s why US Congress members from northeastern coastal states where the sharks are fished are petitioning the Department of Agriculture (USDA), which regulates the industry, to let them unload their surplus on school children, as Southern Fried Science explains. They’re asking for what’s called a “Section 32 purchase” for Atlantic spiny dogfish. That measure authorizes the USDA to buy a food commodity when the surplus is so great that the industry would lose money trying to sell it. The congresspeople write that even though Northeast fishermen have stuck to harvest limits for “groundfish”—species like cod—the populations are not recovering from overfishing. Fishermen could replace these catches with spiny dogfish, they say.

Or they could if they had a market. “Unfortunately, due to lack of a strong existing domestic market and soft market conditions in Europe, Northeastern fishermen and processors have limited opportunities to sell this good product,” the legislators wrote in a letter to the USDA (pdf). “If successful, [the USDA’s use of Section 32] will directly assist the fishing industry in New England through the expansion of domestic markets….”

By “expansion of domestic markets,” they mean the wonders that can be done with deep frying, as industry leaders helpfully suggested (pdf) in a similar letter to the USDA. “Breaded dogfish sticks are ideal for use in domestic food assistance programs and are gaining popularity with chefs seeking a cost efficient fish fillet,” they wrote. The recipients of these Section 32 purchases tend to be public schoolchildren, charities and whoever else the USDA can unload them on.

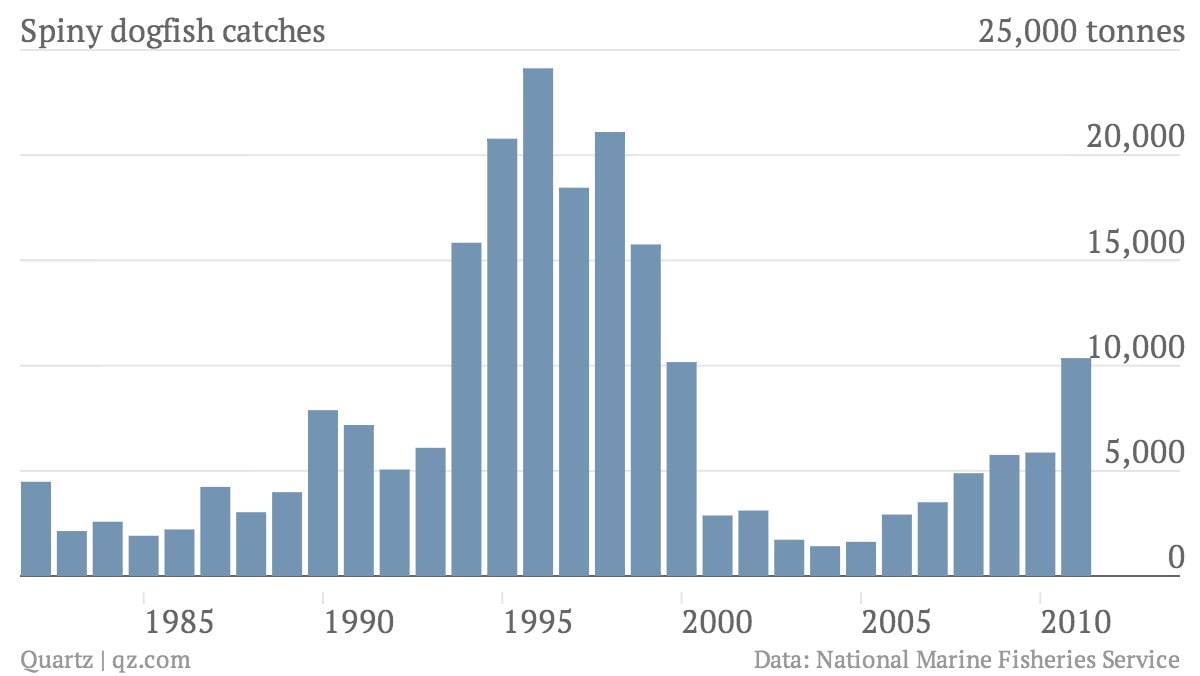

This isn’t a problem likely to go away with a little boost from cafeteria lines. The Atlantic states have been gunning for ever-higher harvest limits on dogfish, making a continuing surplus a pretty safe bet in years to come. Here’s a look at that trend:

The congresspeople remark that the latest annual harvest limit is 40 million pounds (18,000 tonnes) of spiny dogfish. As you can see from the chart above (the available data ends in 2011), that didn’t work out so well last time. The population completely crashed in the late 1990s, after harvest quotas leapt tenfold in less than a decade.

And if the whole “feed it to schoolkids” thing sounds familiar it might be because it is. It’s an old Japanese trick for subsidizing the hunting of animals that no one much wants to eat—in its case, whale meat. Japan’s whole daffy obsession with its right to hunt whales is something the US government opposes, for the good reason that whales are endangered. But if the USDA follows through with its Section 32, it will be doing something similar to Japan—creating artificial demand to prop an industry that might not otherwise exist.