Without its matatus, the city of Nairobi comes to a near standstill. It happens some 10 to 15 times a year when matatu workers go on strike. Whenever they suspend their scramble through the streets, everything in the city slows down. The town center grows quiet, offices sit empty, stores close their doors, and the last lingering pedestrians are able to walk the sidewalks with ease.

There are no commuter trains or trams, the traffic and poor road conditions make cycling impossible, and the government, regrettably, provides only a few irregular and ineffective buses. Since so few people can afford private cars, a majority of people have come to rely upon matatus, the privately owned minibuses that have engulfed the city over the past half a century.

Unfortunately, the citizens of Nairobi have become used to the matatu strikes, used to waiting on dusty side roads and crowded street corners until, angry and out of patience, they abandon hope and either trudge home or hike into town. Whenever the city’s moving mosaic of matatus comes to a stop, the forsaken commuters are once again reminded of just how much their lives depend on these flamboyant minibuses and the army of workers who operate them.

Inevitably, the offices, cafés, and dukas, or shops, begin to echo with resentment, and the muttered complaints of the stranded rise like bitter clouds of exhaust— tumeshindwa kabisa! In other words, without the matatus Nairobi’s commuters feel “completely defeated.” The familiar phrase expresses more than simple frustration at the lack of transportation. It also reveals a sense of thwarted prospects, even a sense of national failure, at least to the extent to which the whole of the city and its economy have come to depend on these vehicles.

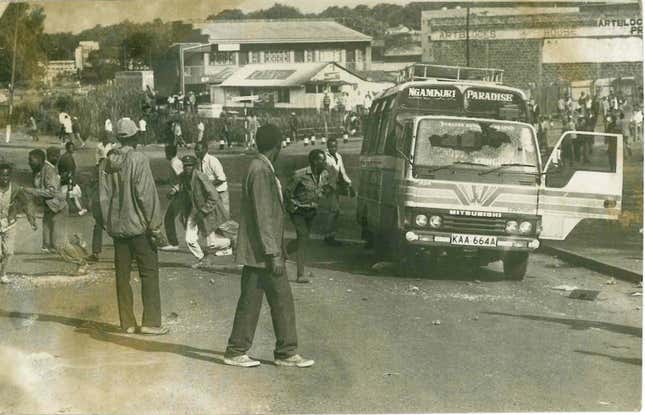

To the uninitiated outsider, this sense of gloom can be baffling. Those unfamiliar with the city’s culture tend to see matatus as little more than a noisy, garish way for residents to get about the city; at worst, they look at the encroaching chaos of matatus as if it were nothing better than a gang of venal marauders— strident, greedy, relentless— intent upon vanquishing the city with their custom- built coaches.

But despite the ambivalence with which the matatus are viewed, the citizens of Nairobi have come to acknowledge, reluctantly, that they are instrumental to the city’s success. It is unlikely that Nairobi’s economy could survive without the overwhelming achievements of the matatu industry.

Since the early 1960s, the matatu has provided transportation to at least 60% of the city’s population, and the matatu industry has become the largest employer in the so-called “popular economy” by providing livelihoods to mechanics, touts, fee collectors, drivers, artists, and other associated businesses.

Even more significant is the fact that the matatu industry is the only major business in Kenya that has continued to be almost entirely locally owned and controlled. In other words, it has, from its beginnings, remained free from the influence of foreign aid or foreign aid workers. The matatu industry is homegrown. The owners and workers are making it on their own, without foreign aid or government support, and despite subsidized competition, government interference, and systemic corruption.

For several decades now, the matatu industry has provided a rare example of a highly profitable business that has turned out to be vital to the development of Nairobi and its identity—as the acclaimed Kenyan writer and activist Binyavanga Wainaina has remarked, “Matatus are Nairobi and Nairobi is matatus.”

In fact, matatus are so much a part of life in the city that it is no exaggeration to say that modern Nairobi could not have taken shape without the invention of these colorful contraptions. The two cannot be separated. They are too mutually dependent, too tightly intertwined. Not only is the motley stampede of transports inescapable to anyone on the street, but they have also, since independence, existed at the heart of the city’s economy and its culture, politics, and street life. They have, over the past half century, provided the city with its circulatory system; they are its lifeblood.

So, to understand the history of Nairobi and its rapid growth, we need to understand the history of the matatu; similarly, if we want to understand the triumph of the matatu, we need to understand the particular social, economic, cultural, and political history of postcolonial Nairobi.

This uneasy alliance of Nairobi and its matatus is the subject of my book, Matatu: A History of Popular Transportation in Nairobi. It is the story of the matatu industry as it unfolds within the larger historical contexts of the community and the nation, from its beginnings in the early 1960s through the authoritarian years of Daniel Arap Moi’s presidency, and into the twenty- first century. Given the industry’s humble origins, as well as its ad hoc, opportunistic nature, the book is necessarily an ethnographic history, written from the perspective of the streets.

The story of the matatu cannot be found anywhere else, anywhere but on the peripheries of society, on the rough streets and in dirty garages, and among the grease- stained entrepreneurs who tend to thrive outside the purview of bureaucrats and politicians— and all too often outside the law. And though the story may start around the margins of Nairobi, it does not end there. Eventually the history of the matatu will take everyone involved— the workers, the passengers, the police, the gangs, and the government— on a rough ride straight into the center of the city.

Excerpted from “Matatu: A History of Popular Transportation in Nairobi,” published by the University of Chicago Press.