Nairobi

On the morning of Apr.13, at the height of Kenya’s primary elections, residents of Busia County in western Kenya woke up to a dose of fake news. The constituents were due to vote in the Orange Democratic Movement party’s gubernatorial race, which pitted lawmaker Paul Otuoma against the county’s governor Sospeter Ojaamong. As voters streamed to the poll, they found leaflets saying Otuoma had defected to the ruling Jubilee Party.

In a region dominated by the opposition ODM party, the circulating pamphlets undermined Otuoma’s candidacy. Even more disquieting was that the leaflets resembled the front page of the Daily Nation, the country’s largest newspaper and paper of record. Speaking to the press, Otuoma said these were “ancient methods” of rigging and that he was confident he was going to win the race. He nevertheless lost the race, claimed the results were flawed and left the party to run for governor as an independent candidate.

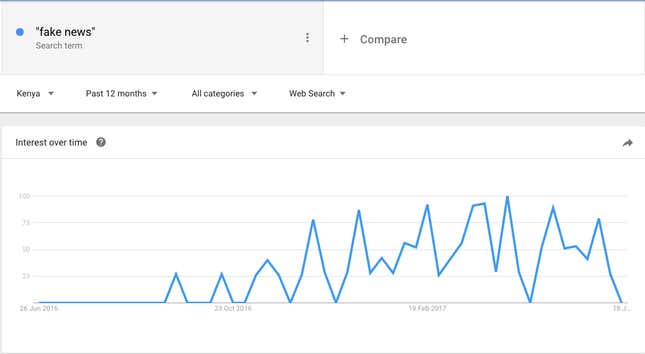

The incident in Busia marked a tipping point in the dissemination of fake stories in the run-up to Kenya’s general elections in August. It also illustrated the manufacturing of falsehoods disguised as news material—not the least on a traditional and trusted medium like a newspaper. The false narratives are also augmented by the endless stream of misinformation, propaganda, and made-up stories currently being shared on social media—a trend that is now worrying both analysts and mainstream media outlets.

Otuoma was right to claim that this type of disinformation was “ancient.” Since the earliest days of printing, fake stories were used as a commercial strategy to sell pamphlets, books, and newspapers. But the internet has edged all that out, fueling sensationalist and bogus stories that get shared far and wide.

Across Africa, false stories have been peddled about the spread of Ebola to the death of showbiz celebrities. And the problem was, however, more visible during the 2016 US presidential elections when Macedonian teens were writing and sharing stories about Donald Trump or and Hillary Clinton.

In Kenya, attempts at propaganda and misinformation are becoming more discernable as the election season gets underway. The stakes are also elevated by the ubiquity of connectivity among the electorate: mobile penetration among Kenya’s 44 million people is up to 87%, and the country has one of the fastest mobile internet speeds in the world. Kenya also boasts some of the most youthful voters in the east Africa region, who tweet a lot, and are increasingly dependent on online news for information. And in a nation where politics is often considered the ‘national sport,’ and where ethnicity defines the electoral agenda more than issues, observers say misinformation can be used to play at inherent beliefs and biases.

Nanjira Sambuli, the digital equality advocacy manager at the Web Foundation says the electorate and the media should be cognizant of these trends. “We have to proceed carefully,” Sambuli says, “and not operate on sheer alarmism, but carefully assess what’s put forth from various quarters.”

The information propaganda is being spread on Twitter as hashtags, paid search on Google as well as sponsored posts and ads on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram timelines. For instance, in late May, the hashtag #DavidNdiiExposed started trending in Kenya, supposedly aimed as a takedown of the prominent economist David Ndii, who is often critical of the government’s economic and development policies. The attack didn’t do well among Kenyans but was a harbinger of the campaign of misinformation lurking in social media.

Local Kenyan political operatives have also been registering fake news websites like something called Foreign Policy Journal (fp-news.com) or CNN Channel 1 (cnnchannel1.com)to propagate false stories during the election. The sites have corresponding names or brand colors matching international media outlets, all in an effort to give their stories added credibility. For instance, the FP News site generates stories supposedly written by someone called Thomas Greenfield whose bio claims to have written for Quartz (he has not). It’s worth noting Thomas Greenfield is the surname of former US assistant secretary of state for Africa, Linda Thomas-Greenfield.

The FP News was exposed on Twitter earlier this year as being administered by one Francis Njuguna. FP News carries stories like how Western think tanks believe president Uhuru Kenyatta will win a majority of the vote, even when polls show that the race is tight. Another article reported on how the opposition leader Raila Odinga was orchestrating the recent attacks on white-owned ranches and conservations in Kenya. In fact, a majority of the articles on the site are against Odinga, drawing either false conclusions about his past, distorting or selectively omitting facts, or providing no context.

Alphonce Shiundu, the Kenya editor for Africa Check says not everyone is discerning to know a fake for what it is. “Fighting propaganda online requires elements of media literacy,” Shiundu says. “Some may know it is fake, or false, or incorrect, but they still pass it on because they think it is funny.” The onus to verify information and to expose the purveyors of half-truths, Shiundu says, squarely falls on journalists.

But in a high-stakes election like this one, the explosion of false stories upends the role of mainstream media, considered the most trusted institution in the country. This presents a challenge to the journalism fraternity, different from the 2007 elections, when local language radio stations took part in inciting the violence that led to the death of more than 1,000 people.

“Dark social”

Sambuli says that Kenyans on Twitter—better known as KOT—are cynical, and are quick, like in the case of the hashtag against Ndii, to question false narratives. But she says she’s worried about the “dark social” apps like WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger or emails where information shared cannot be measured or questioned publicly.

A lot of the information propaganda in Kenya, she noted, was also “driven by local actors, even though it’s alleged that some quarters are hiring foreign companies versed in micro-profiling to lead the charge.”

In 2013, Kenya’s government hired the UK-based public relations firm BTP Advisers to “develop a compelling political narrative” even though president Kenyatta had just been indicted at the International Criminal Court. Local media reports also claim the president has hired Cambridge Analytica, a company at the center of a growing controversy over the use of personal data to influence both the Brexit vote in the UK and the Donald Trump election in the US. Cambridge acknowledges that it worked for a “leading Kenyan political party” in 2013 to conduct and implement the largest political research project in East Africa—but denies it is working on Kenyatta’s campaign now.

Sambuli says that sharing timely and factual information with audiences helps forestall misinformation from running amok. The media was still a primary source of information for many Kenyans, and she said they shouldn’t squander the opportunity to step in during these critical times. “Asking how, why and other probings go a long way in assessing accuracy and credibility of information, which is everywhere these days.”