Liu Xiaobo, winner of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize and one of China’s greatest thinkers and pro-democracy activists, is in dire health, diagnosed with terminal liver cancer after serving nine years out of an 11-year sentence for “inciting subversion of state power.” I found out about my friend’s illness on Monday (June 26), as information from his lawyers spread across social media, close to a month after he was reportedly diagnosed with cancer.

The Liaoning Prison Administrative Bureau released a statement Monday saying that Liu has been granted medical treatment outside prison. It is not yet clear at this stage how much his legal status has changed, with some news outlets reporting that he is now free, and others that he has been only transferred for treatment.

What is known is that Liu is now in a Shenyang hospital in a serious condition, and that China’s repressive apparatus may finally get what it has always wanted from him: his absolute silence.

I first met Liu in 1988, when I was a very young student at Beijing Normal University, where I was learning Chinese and he was teaching Comparative Literature. A friend of mine, from the Chinese Literature Department, was adamant that he was the best professor in the whole of Beijing, and that I should go to his lectures. My language skills were pathetically insufficient for the task, but I sat through it all because I was enraptured by the excitement that he inspired in the classroom—not because I knew what he was debating. He spoke in bursts of excitement, with an occasional stammer that made him all the more determined to make his point forcefully. He smiled and cracked jokes making everyone laugh, showing a charisma rarely seen in Chinese university professors at the time. My own Chinese language classes were a soporific mash of morally uplifting stories with a Communist slant, and were often deserted by the students.

When the protest movement at Tiananmen Square started, after the death of former leader Hu Yaobang, Liu soon joined to be near his students. He stayed in the square until the very end, negotiating with the soldiers who were clearing the area to let the remaining students make their way back to their dormitories unharmed. His courage may have saved countless lives—yet that is when he was first jailed, as his support for the protesters was called “counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement.” He served nearly two years in prison.

Prior to that, though, he had already been ruffling the establishment: He had no qualms in writing and saying that China needed freedom, and greater democracy. Even if the late 1980s were way more liberal than anything that China has seen since, his iconoclasm was more than many could tolerate. He once quipped that China “will of course need 300 years of colonialism” since Hong Kong, with 150 years under the British crown, was wealthier and freer—and China’s demonizing propaganda latched onto this to prove his lack of patriotism. Yet, despite this supposed lack of patriotic feeling, he always refused to seek safety abroad, and after a few trips, afraid of not being allowed back, stayed in China in spite of the risk.

I met him again a few years later—finally able to communicate in better Chinese—and he gave me his memoir about Tiananmen and his role in it. It was a wad of photocopied papers from a book that was already banned in China—as all his writing had become, and remains to this day. He had been suspended from university, and he could not publish in the country, but was able to write only in overseas publications: “That’s what they turned me into. I used to be a public intellectual, at university, and now I am a professional dissident. I’d rather be something else, but they chose for me,” he told me.

On another occasion, as we were having an ice cream in Beijing at one of China’s first ice cream parlors, by the Friendship Store (which, in the early 1990s, was still the only place where you could buy certain imported goods), he got mad at a musician friend who had casually taken a cigarette from his packet: “See? This is communism. You think you can just take what is not yours. Ask me for a cigarette, and I’ll give you all the ones you want,” he said very seriously. Being a “professional dissident” meant that every small gesture had to be political, I realized, and that he would regard everyone he was with as making a political statement no matter how trivial their actions.

We met many more times after that, as he went in and out of prison—and I always learned from him much more than he ever learned from me.

In 2008—that momentous year when China was getting ready to host the Olympic games, and when riots erupted in Tibet, first, and then a dreadful earthquake destroyed Wenchuan, in Sichuan, leaving more than 70,000 people dead—Liu Xiaobo took part in drafting one of the most important documents to ever come out of Chinese dissidence. It was called Charter 08, inspired by the Charter 77 written in 1977 by Czech and Slovak intellectuals and dissidents, and it asked for everything the Communist Party has never been willing to give.

It asked the Party to recognize that freedom, equality, and human rights are universal values, and for a system that, maybe through making China a federation, would grant its minority populations (in areas such as Tibet and Xinjiang) genuine autonomy, as they have long been promised. In other words, it asked the Communist Party to relinquish its obsessive control over its population, over the information that is allowed to circulate in the country, and for an independent judiciary.

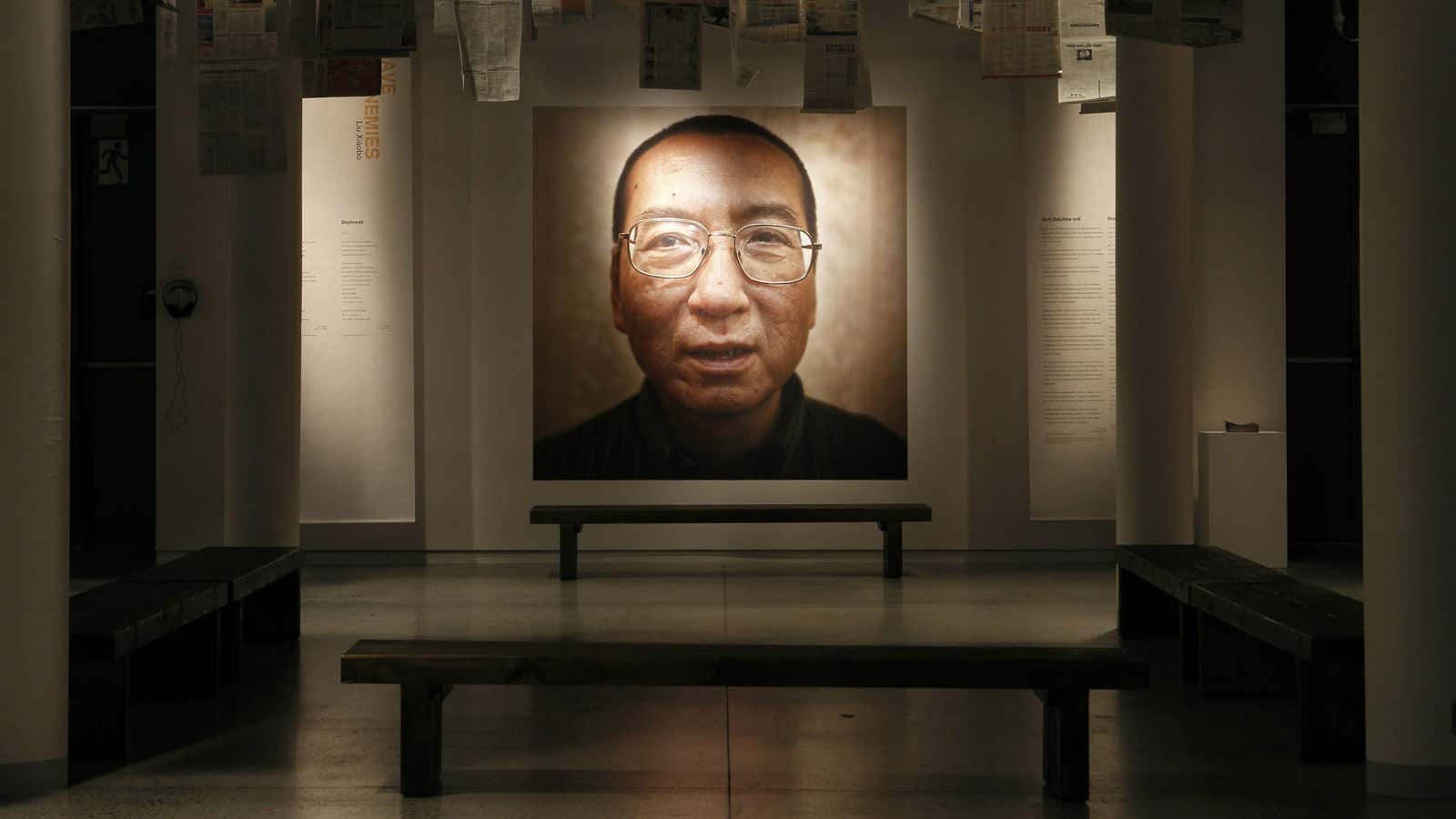

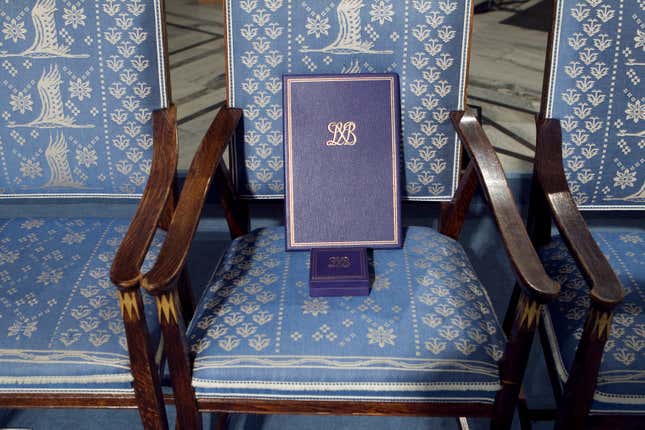

Liu was arrested for the last time soon after that, sentenced in 2009, and awarded the Nobel Prize the year after. China went into a frenzy of condemnation and denial, even taking its fury out on the salmon fishing industry in Norway. He was obviously not allowed at the ceremony, and actress Liv Ullman read from his self-defense speech at his trial: “I have no enemies,” he said, as he prepared to face jail. A text that still brings tears to those who read it, for its humanity, its courage, and intelligence:

I have no enemies and no hatred. None of the police who monitored, arrested, and interrogated me, none of the prosecutors who indicted me, and none of the judges who judged me are my enemies. Although there is no way I can accept your monitoring, arrests, indictments, and verdicts, I respect your professions and your integrity…

Hatred can rot away at a person’s intelligence and conscience. Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress toward freedom and democracy. That is why I hope to be able to transcend my personal experiences as I look upon our nation’s development and social change, to counter the regime’s hostility with utmost goodwill, and to dispel hatred with love.

A voice so free and capable of such sharp analysis should have been cherished by a developing country that, after becoming in the shortest imaginable time the second-largest economy in the world, has been trying to increase its “soft power” and improve its image among people both near and far.

Instead, Liu is considered a criminal, and he and his close family have been suffering under the darkest side of China. His wife, the poet Liu Xia, has been put under house arrest since he was awarded the Nobel Prize, where she has been suffering the torments of isolation and deep depression. She suffered from a heart attack two years ago, and was hospitalized. Her brother, Liu Hui, was sentenced to 11 years in prison in 2013 for fraud, in a trial that was widely condemned for its many irregularities. At the time, activists denounced the sentencing of Liu Hui as a clear attempt at intimidating the extended family of Liu Xiaobo.

Far from being the personal sorrow of a friend taken so gravely ill after years of hardship, this is China’s sorrow, too. It has an obsession with control so strong that it is rendered incapable of celebrating its most inspiring people, and of cherishing the wealth that sparks from free minds, free thinking, and diversity.