Travis Kalanick’s bosses share just as much blame for the Uber calamity

Blaming the Uber calamity on the recently deposed CEO Travis Kalanick is convenient, but let’s not forget the less visible but just as problematic role that the board of directors played as they let Uber unravel. Given the board’s complicity, can the company fashion a spectacular turnaround, or will it be a quick flameout?

Blaming the Uber calamity on the recently deposed CEO Travis Kalanick is convenient, but let’s not forget the less visible but just as problematic role that the board of directors played as they let Uber unravel. Given the board’s complicity, can the company fashion a spectacular turnaround, or will it be a quick flameout?

When Uber emerged a few years ago, I was thrilled. As I wrote in “In Praise of Uber” a year ago, Uber provided a relief from the terrors of the local cabbie, both in Paris and in my adopted Bay Area:

…pleasant rides with charming drivers are rare exceptions in a succession of dirty Silicon Valley cabs with cracked windshields, duct taped seats, noisy wheel bearings threatening to seize at any minute. In Paris, artful cabbies need to be reminded that I’m not a visitor who needs a tour of the city. Sitting in the back, I squirm each time the cabbie plays with the zone setting on the “grinder,” as Parisians call the meter, a sentiment Woody Allen immortalized in Annie Hall: “You’re so beautiful I can hardly keep my eyes on the meter.”

Simply finding a cab can be an unpleasant, complicated experience. Try getting a ride at the wrong time of day, when it’s raining, in the wrong part of town, or for a destination that’s unlikely to provide a return fare.

A decade ago, all of the components of a modern, web-enabled taxi service—GPS navigation, smartphones, cloud computing, ubiquitous wireless network connections—were waiting for someone to figure it out. The incumbent taxi organizations had their chance—they had the cars, after all—but they ignored the technology and infrastructure advances.

Why? Because they had a stranglehold. In too many cities, the taxi service relies on an excessively cosy, marginally ethical partnership with the local government. Municipal taxi licenses, called medallions here and plaques in Paris, limit the number of cabs and thus drives up prices of both medallions and fares. In 2013–2014, a New York City medallion traded for more than $1 million, and Parisian plaques about €250,000 ($340,000).

When UberCab (as the company was then called) emerged in 2009, the taxi companies and their city accomplices were befuddled and angry as the upstart pushed them around. Users loved the point-and-click access to rides right from their smartphones, night and day, rain or shine, and the “Anybody can drive for Uber” philosophy opened a world of possibilities for unemployed and underemployed drivers.

This still-rebellious old geek loved the new scene. The previously uncertain price for a taxi ride downtown from Charles De Gaulle was set at a dependable €55. From her iPhone, my spouse could remotely order a ride for her aging mother living in a Paris suburb… and then call the driver to set up a more convenient pickup location. These aren’t peculiar examples, they’re part of the usual, pleasant Uber customer experience.

I was so enamored of Uber’s manhandling of the incumbents that I allowed myself a bro joke:

Uber’s CEO Travis Kalanick doesn’t brush his teeth in the morning, he files them.

Ha ha, funny… until the unsettling rumors surrounding Kalanick and his company began to trickle in. As weeks passed, the trickle became a surreal flow. From sexual abuse to invasion of privacy, stealing wages from drivers, misappropriating intellectual property, spying on a whistleblower, charging passengers non-existent fees, violence, tracking government employees with special software, hacking smartphones to follow users even when the Uber app is off…

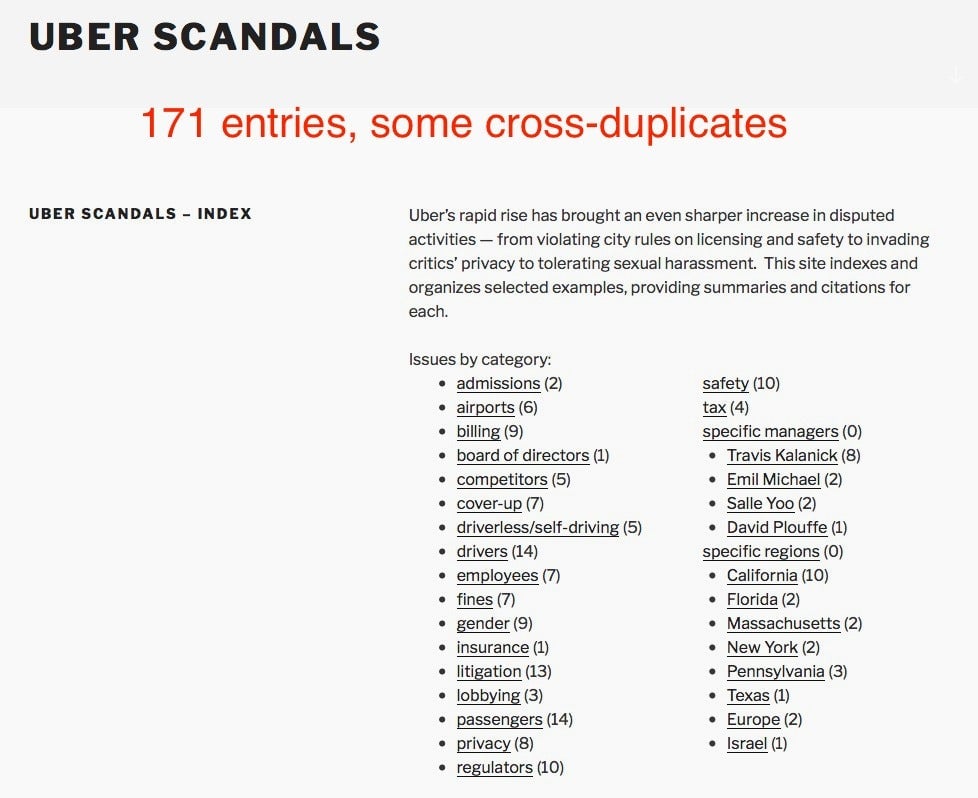

To be sure, many of the allegations have been disputed, but the extent of the litany was disturbing. Look at this screen capture from the uberscandals.org site, which has been logging complaints against Uber since 2013:

Misdeeds aplenty, but the board of directors did nothing… until a blog post by Uber engineer Susan Fowler recounted unwanted sexual advances by a superior. Even more damning was Human Resource’s astonishing response: Not only was the “superior” too valuable to be fired, Fowler should watch her step [as always, edits and emphasis mine]:

…my manager scheduled a 1:1 with me, and told me we needed to have a difficult conversation. He told me I was on very thin ice for reporting his manager to HR. California is an at-will employment state, he said, which means we can fire you if you ever do this again. I told him that was illegal, and he replied that he had been a manager for a long time, he knew what was illegal, and threatening to fire me for reporting things to HR was not illegal. I reported his threat immediately after the meeting to both HR and to the CTO: they both admitted that this was illegal, but none of them did anything. (I was told much later that they didn’t do anything because the manager who threatened me “was a high performer.”)

Fearing that she was being investigated for complaining, Fowler hired an employment attorney. Three months later, Kalanick is forced to resign.

Justice is served.

Not quite.

Deposing Kalanick may be justified, but focusing the blame on him is wrong, an easy out. As the uberscandals.org site documents, Uber’s bad behavior predated the Fowler incident by at least four years. This leads us to a question for Uber board members: What did you know, and when did you know it?

Can anyone believe that the company’s directors were unaware of Uber’s many abuses? Of course not. So why did they “hear no evil, see no evil” for so long?

The answer is in three letters: IPO.

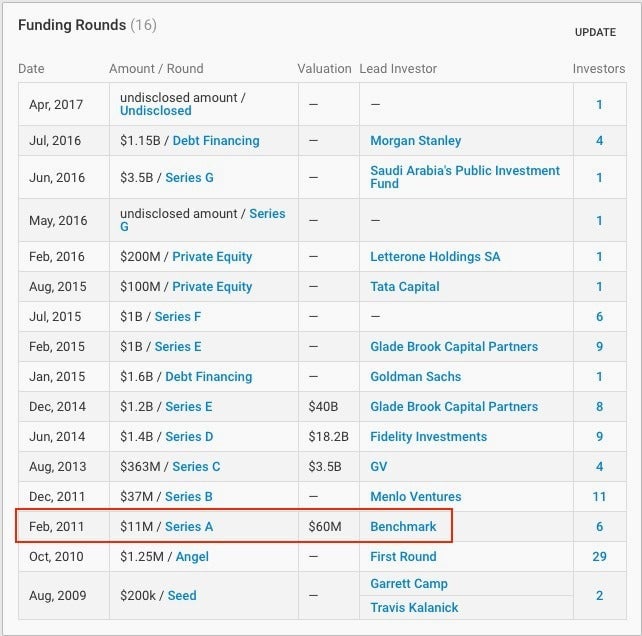

Uber’s investors have put approximately $16 billion in play:

Let’s look at one early investor, Benchmark. They put in $11 million for a $60 million valuation. What would their stake be worth at the 1,000 times higher $68 billion valuation aired in a June 2016 Wall Street Journal article? It’s impossible to know without looking at the exact terms of all the subsequent rounds, and the multiple could still grow because late stage 2017 investors are somehow “promised” a higher IPO valuation than the one at the time of their investment.

In a publicly traded company, directors are fiduciaries, accountable to the “widows and orphans,” i.e. ordinary investors—owners of company shares. But at Uber, directors are accountable only to themselves, with the exception of “outside” directors who are recruited for their expertise and tech aura…and richly compensated with shares in the company.

With this in mind, we see why Uber’s board of directors let Kalanick run the company the way he did. Uber’s investors had one goal—the IPO—and one strategy: create a market position so dominant that it would eliminate the competition and, as a result, provide the pricing power that would support a stratospheric IPO price. As for tactics, investors left the matter to Kalanick while looking elsewhere.

Only when the scandals went too far, only when Susan Fowler courageously told her story—not just of abuse but of inhumane (and possibly illegal) HR reaction—did the board wake up and fire the Chief Guilty Officer.

But that’s not the end of the story, far from it.

Naturally, the firing was bracketed with the usual gesticulations. Counseling, meditation, and “more sleep” for the CEO; promises to reform Uber’s culture; a long report from the Covington law firm following an inquest led by former US attorney general Eric Holder.

The Covington report, with its endless recommendations, points once again to the breadth and depth of Uber’s problem. The suggestions include hiring a chief operating officer, enhancing board oversight (!) and internal controls, improving Human Resources’ record-keeping, and reformulating Uber’s 14 (!) Cultural Values. They then dissolve into unimpeachably “good things” such as broadening training initiatives, strengthening the complaint process, enhancing diversity and inclusion… Nothing one can disagree with. Well, perhaps this one:

The problem with these recommendations is that they’re not layered in order of importance. They’re not prioritized into 1) do-or-die, 2) needed to move forward, and 3) nice-to-have.

Which leads us to Uber’s future after Travis Kalanick.

But wait, he’s not gone! TK is still a member of the board where he holds a significant but difficult-to-compute share of voting rights. How would you like to be the newly-hired CEO with the supposedly disgraced former chief as your boss? This is your mission: Reform company culture—but don’t wreck the IPO valuation.

A company’s culture isn’t realized in its “Statement of Values” or its catered dinners. The culture lies under the skin of its employees and is felt by its customers. The culture grants permission to emote, to think, and to do—and is extremely hard to change. How many large, globe-spanning companies have really changed their culture—as opposed to letting it decay?

Uber’s culture was born from filed teeth. Defanged, its business model will be undifferentiated, easily replicated by competitors who have already started deploying network infrastructure and smartphone apps.

* * *

Postscript

A recent Harvard Business Review article, well worth the read, argues that Uber not only lifted its business model from Lyft, but that it’s an illegal operation that should be shut down.