The cyber attack that knocked out Ukraine this morning is now going global

The ransomware that took out critical services in Ukraine this morning has now spread to computers worldwide with the help of leaked hacking tools allegedly developed by the US National Security Agency (NSA). The strain of ransomware being used in the attack is known as Petya, though some are calling it NotPetya due to disagreements over its core code. Petya/NotPetya has now hit Russia, Denmark, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Infected computers have their files locked, and the hackers demand users pay $300 in bitcoin to get them back.

The ransomware that took out critical services in Ukraine this morning has now spread to computers worldwide with the help of leaked hacking tools allegedly developed by the US National Security Agency (NSA). The strain of ransomware being used in the attack is known as Petya, though some are calling it NotPetya due to disagreements over its core code. Petya/NotPetya has now hit Russia, Denmark, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Infected computers have their files locked, and the hackers demand users pay $300 in bitcoin to get them back.

It was late afternoon in Ukraine when, in the space of hours, the country’s government, top energy companies, private and state banks, main airport, and Kyiv’s metro system all reported hits on their systems. The attacker was not immediately clear—Wired, in a recent story, described Russia as using its neighbor as a ”test lab for cyber war,” but Moscow denies any part in past attacks. Its own state oil giant Rosneft also reported being hit by a cyberattack today; Rosneft’s website was unresponsive at time of writing. It’s unclear if the attacks are linked. Another Russian oil firm, Bashneft, has been hit too.

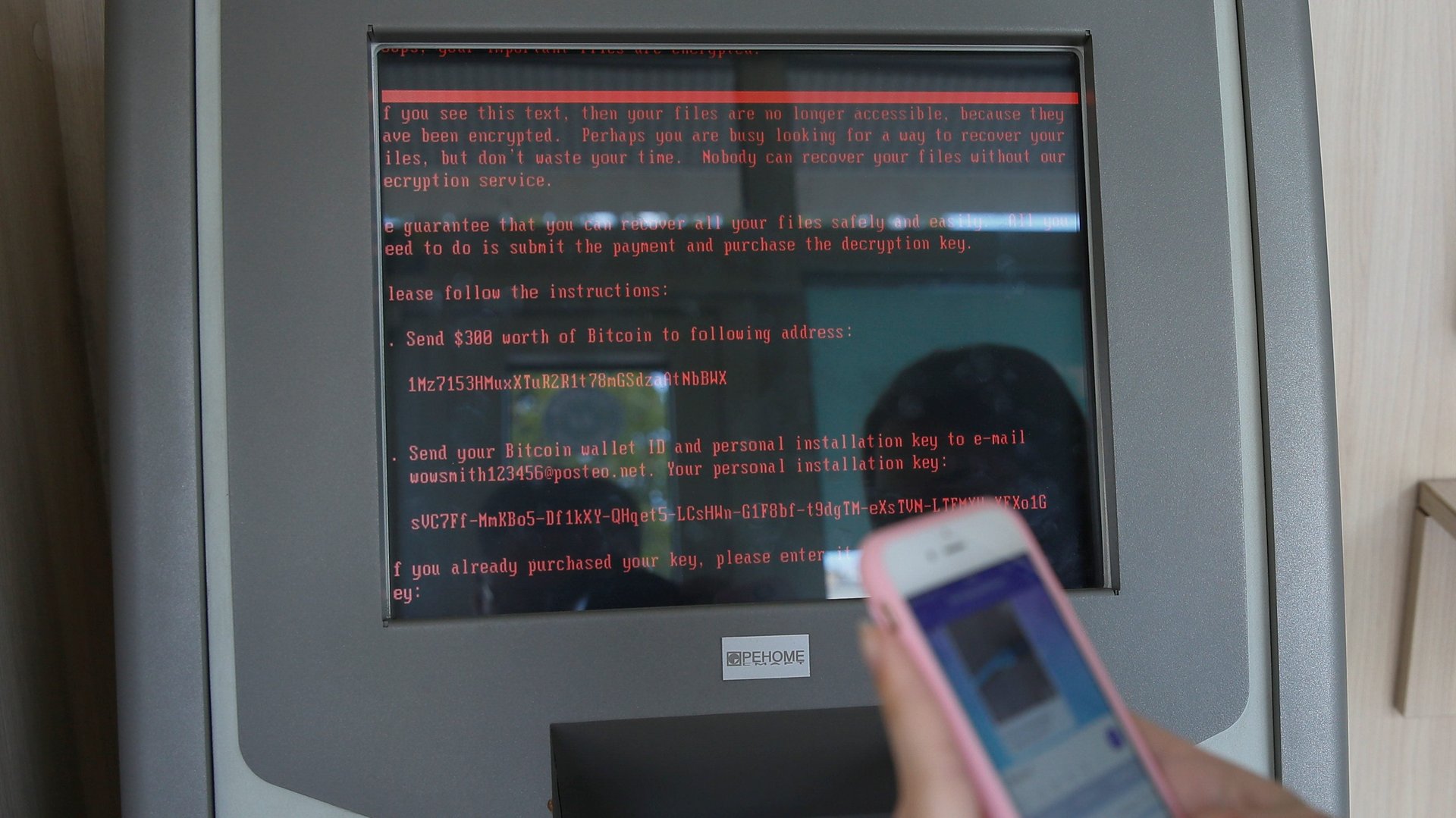

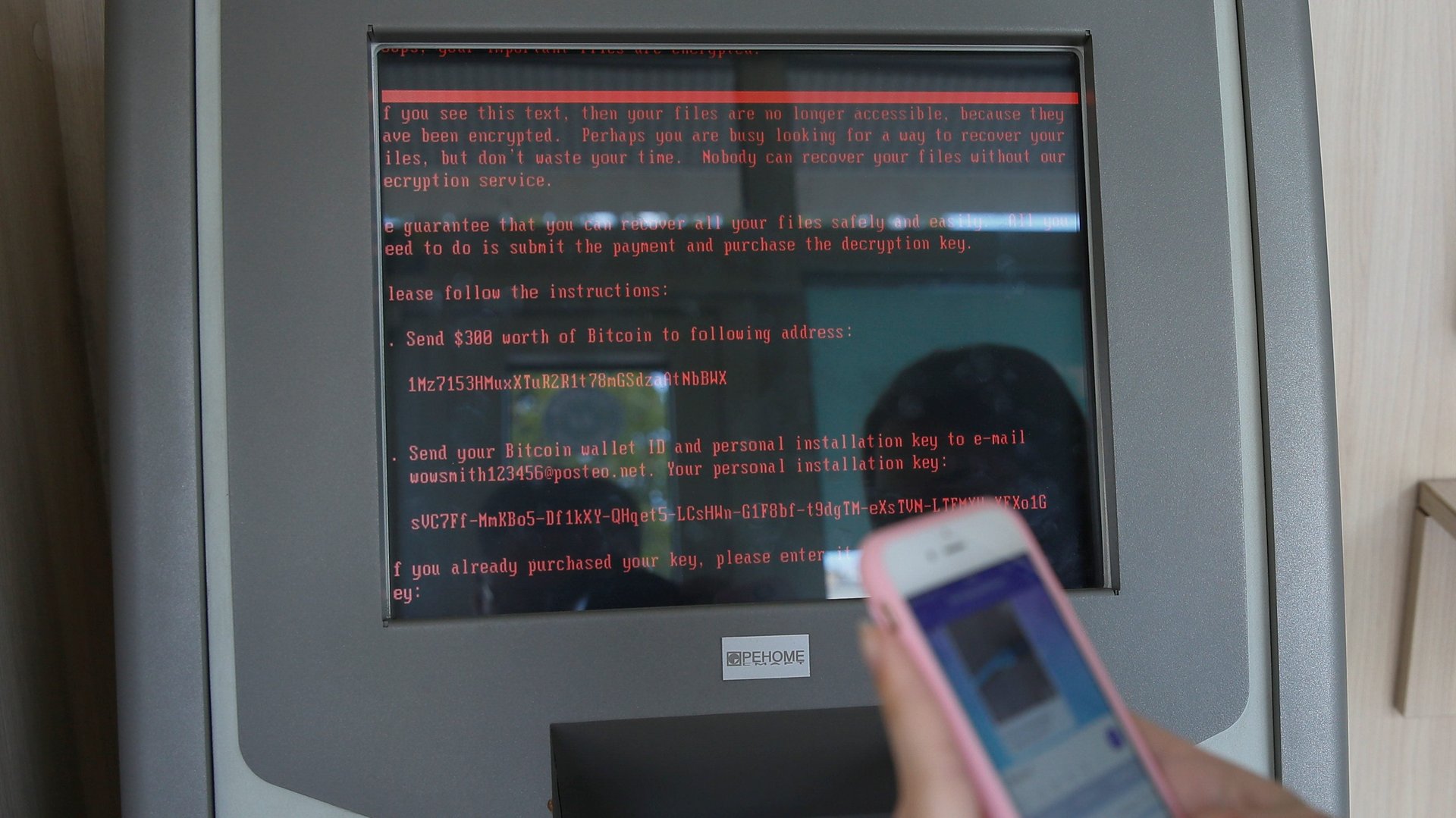

Ukraine’s deputy prime minister, Pavlo Rozenko, said government computers had been taken over with the screen below appearing:

Several security companies, including Symantec and McAfee, have confirmed that Petya/NotPetya is using at least one of the same tools that made the WannaCry ransomware attack on May 12 so successful. The quick proliferation of that attack, which infected nearly 300,000 computers worldwide within a day, was due entirely to its use of two powerful software exploits that were released to the public in April by an anonymous hacker group calling itself the Shadow Brokers, which said the exploits were developed by the NSA. Governments and experts have generally come to the conclusion that the North Korean government was behind the WannaCry attack.

Ukraine’s central bank was tight-lipped about the attack, declining to say which banks had been hit but acknowledging they were “having difficulties with client services and banking operations.” It told Reuters it was confident in its defenses against cyber fraud. Meanwhile, state energy provider Ukrenergo said an attack on its IT system had not affected service.

The deputy director of Kyiv’s Borispol airport wrote on Facebook (link in Russian) that it had come under a “spam attack” and flights might be delayed. At the time of writing, the airport’s website was down. Kyiv’s metro system said its card payment system was down (link in Ukrainian), blaming a hack.

The Ukrainian government’s official Twitter account said there was “no need to panic,” with a GIF suggesting the very opposite:

Outside Ukraine, British advertising agency WPP also said it had been hit by ransomware, while Danish shipping and oil group Maersk reported its IT systems had been taken down. In the United States, the pharmaceutical giant Merck said on Twitter that its network was compromised. A hospital in Pittsburgh was also hit with a cyber attack, but it’s not yet clear whether it was related to Petya/NotPetya.

The alleged NSA tool Petya/NotPetya is using, EternalBlue, exploits vulnerability in the Windows operating system that allows the ransomware to copy itself onto a target computer and gain access to its files. Microsoft released a patch for the vulnerability in March, about a month before the Shadow Brokers released EternalBlue, but that patch may not be enough to protect users from Petya. Eric Chien, the technical director of Symantec’s security response division, said the new ransomware is also using another method to copy itself.

“Petya uses the EternalBlue exploit to propagate itself,” Chien said in an email. “However, there is code that allows it to spread via [the Windows file-sharing service] SMB with the current user’s credentials.”

That is, in addition to using EternalBlue to spread, Petya also steals login information from any computer it infects, and attempts to use those credentials to spread throughout the local network it’s on, posing as a legitimate user. There’s no current patch to stop that method of proliferation, and in fact, it takes advantage of functionality so core to Windows that it may not be something that can be patched. However, one potential method for protecting Windows computers, which involves adding a certain file to the C:Windows directory, has been uncovered by researchers.

WannaCry’s spread was halted when a researcher discovered that every time the ransomware infected a new computer, it tried to reach a certain web page that didn’t exist. The researcher registered a website at that address, and it turned out to act as a “kill switch,” signaling to the ransomware that it should shut down. Researchers have not yet identified a similar kill switch associated with the Petya/NotPetya.

Experts have suggested that WannaCry, despite its rapid proliferation, was a poor implementation of the powerful tools it used, and that a better-developed ransomware could cause far more chaos.

Early signs of Petya, however, show that its developers may have made at least one of the same mistakes as the WannaCry attackers. In all of the screenshots of Petya-infected computers we’ve seen on social media so far, it instructs the victim to send a payment to the same bitcoin address. In a typical ransomware attack, a unique bitcoin address is generated for each victim. Without it, the attackers can’t identify who’s paid and unlock their computers—which, once discovered, makes it less likely people will pay. WannaCry, although it infected nearly hundreds of thousands of computers worldwide, *similarly* asked each victim to send money to one of just three bitcoin accounts.

We’ve setup a Twitter bot, @petya_payments, that will tweet each time a new ransom payment is made to the bitcoin wallets associated with the Petya attack. So far we only know of one wallet the ransomware is instructing victims to send money to, and will add more if they surface:

This post was updated with new details at 7:00 p.m. ET on June 27