The Republicans’ Medicaid cuts, if they pass, will disproportionately hurt black Americans

Everyone knows by now that the Republican health-care reform being pushed through the US Congress is going to be tough on the poor. What’s less appreciated is that it’s going to be disproportionately tough on black Americans—and not just because they are more likely than white people to be poor.

Everyone knows by now that the Republican health-care reform being pushed through the US Congress is going to be tough on the poor. What’s less appreciated is that it’s going to be disproportionately tough on black Americans—and not just because they are more likely than white people to be poor.

Cuts to Medicaid, the federally funded health-care program for the poor, are the chief reason the health-care law in its current draft is projected to leave 22 million more Americans without health insurance by 2026. If Congress approves the cuts, state governments will have to make up the shortfall. Under the bill passed by the House in May, that’s $834 billion over the next 10 years; under the one currently in the Senate, $772 billion.

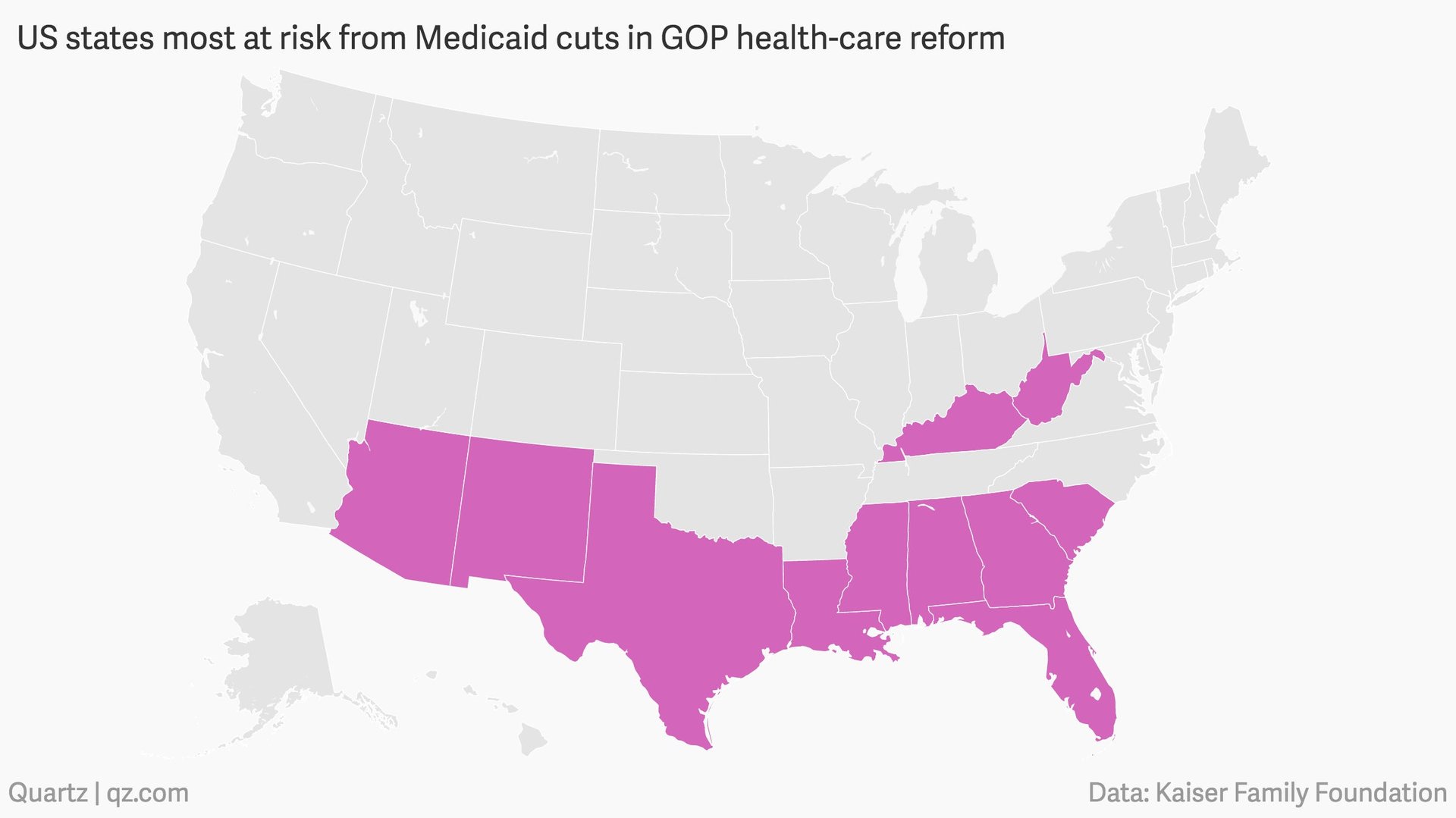

Some states will be able to handle that better than others. A report by the Kaiser Family Foundation pinpoints 11 states as “high-risk,” based on 30 factors, from race to age to poverty levels. Of these 11 states, five are among the 10 US states with the highest percentage of black citizens: Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina.

That correlation is in part because black Americans are disproportionately poor and thus disproportionately dependent on Medicaid: Around 28% of black adults under 65 are on the program, nationwide, against 16% of whites. But there are several other factors that will make those states with large black populations struggle to compensate for the loss of federal funds.

Risk factors

Five basic things will affect how well a state can plug the funding gap, the Kaiser report found: Medicaid policy choices (meaning how much Medicaid funding states opted to receive in the past); demographics; the health profile of the population; state revenue and budget choices; and health-care costs and access. Within those characteristics, Kaiser identified specific measures, like unemployment rate and number of people over the age of 85, that can make a state “high-risk.”

Judging from the recent proposals, the new health-care law will probably include caps on how much Medicaid a state gets based on the state’s past spending. That gives states little wiggle room to change how they spend in the future.

States with high poverty and unemployment levels already struggle to provide Medicaid to those who need it. The same goes for states with a low “health status”, such as those with large populations of disabled or mentally ill people, who need expensive long-term care. Cuts to the program will be especially hard on them.

States that earn relatively low tax revenues will automatically struggle to pay the bill that federal funding leaves behind. And states in areas with high health-care costs and shortages of doctors and nurses will have an even harder time.

High-risk states

These are the 11 states the Kaiser report identifies as having the most simultaneous risk factors.

Five of them are also in the top 10 (pdf) for largest African American populations:

These states are in the south and among America’s poorest, so it’s reasonable to assume that the proportions of both black and white people on Medicaid will be even higher than the national averages (we weren’t able to obtain state-by-state data).

People living in high-risk states will see their state governments struggle if federal funding is cut, and black people, and other people of color, will be especially hurt, Kaiser said. “Proposed cuts would have significant consequences for people of color,” Samantha Artiga, associate director of the Kaiser Family Foundation’s program on Medicaid, “because Medicaid plays a central role in supplying health coverage” for these communities.

“People of color were the most likely groups to gain coverage and access to care under the ACA, and in the centuries-old struggle over health, they have never been closer both to racial equality of, access and to the federal protection of health care as a civil right,” the Atlantic recently explained. “But if Republicans have their way, that dream will be deferred.”