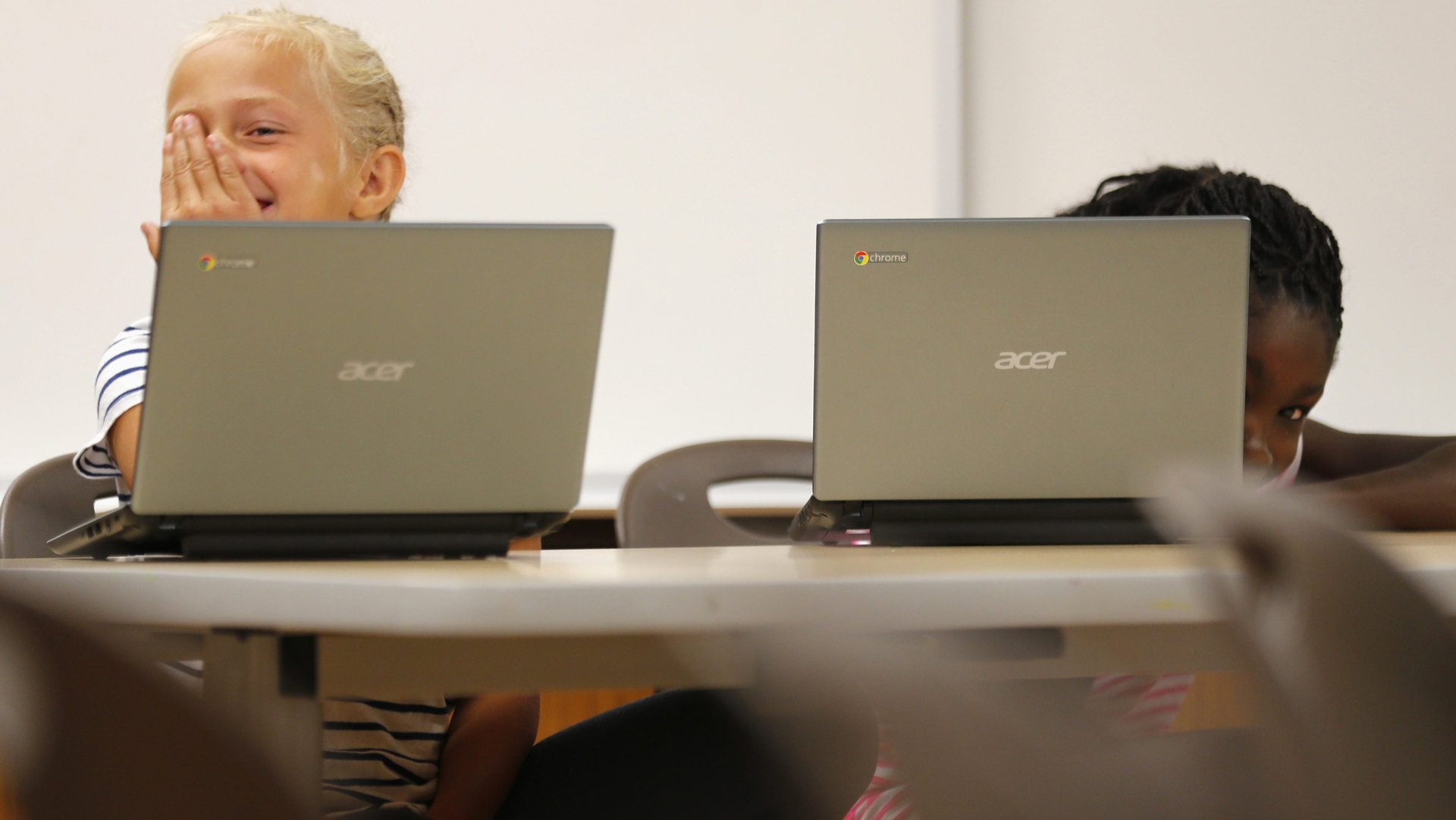

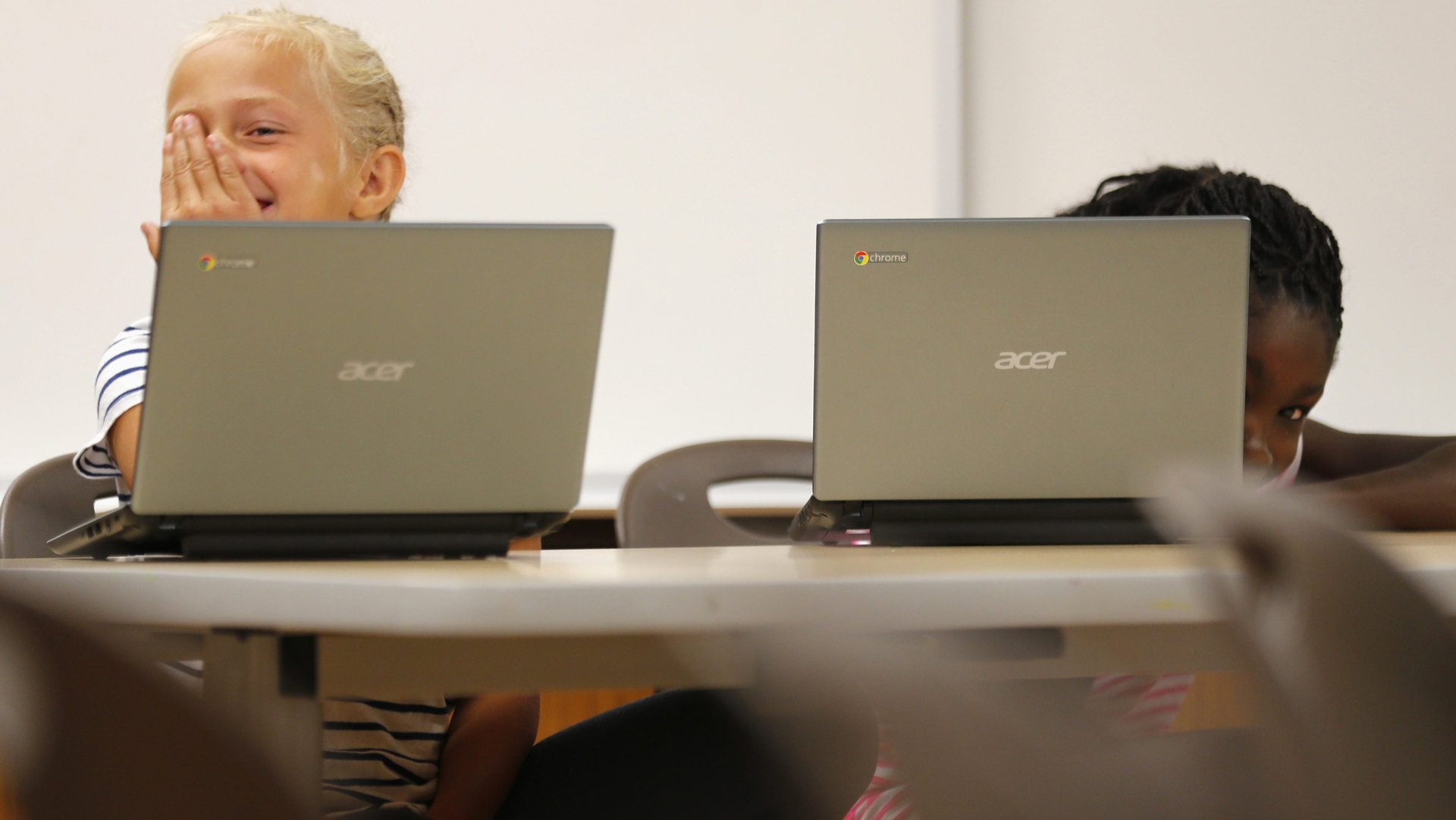

A study shows black girls are seen as less innocent than white girls—which dehumanizes them

That black children in America are much more likely than their white peers to be disciplined at school or end up in the juvenile justice system is well established. The disparity between black girls and white girls is even more acute than among boys. A new study suggests a reason: Black girls are viewed as less innocent and more “adult-like.”

That black children in America are much more likely than their white peers to be disciplined at school or end up in the juvenile justice system is well established. The disparity between black girls and white girls is even more acute than among boys. A new study suggests a reason: Black girls are viewed as less innocent and more “adult-like.”

The study, from Georgetown Law School’s Center on Poverty and Inequality, finds that Americans think black girls need less support and comfort than white girls. They believe they are more knowledgeable about sex, and other adult topics, and are also more likely than white girls to take on adult roles and responsibilities. These views apply to children as young as 5, and are particularly strong toward girls aged 10-14, which the authors say is a crucial period for a child’s identity development.

The study draws on previous work on black boys, who were also found to be more likely to be perceived as older than they were than white boys, and more likely to be viewed as guilty of a crime. But while black boys are, for instance, 1.5 times more likely to be punished for disruptive behavior at school than their white peers, black girls are 3 times more likely to be disciplined than white girls, according to a recent study in Kentucky. Nearly the same effect is true for fighting at school.

“Ultimately, adultification is a form of dehumanization, robbing black children of the very essence of what makes childhood distinct from all other developmental periods: innocence,” authors of the study write. “Adultification contributes to a false narrative that black youths’ transgressions are intentional and malicious, instead of the result of immature decision-making—a key characteristic of childhood.”

The study, conducted with 325 US adults — a relatively small sample size — who were recruited online (and primarily white), does not set out to make a definitive causal link between this so-called “adultification” of black girls and the fact that that they are incarcerated and disciplined at higher rates than white girls. But it makes a strong suggestion that the two could be linked, and stipulates that it is just the first step in an area that has not yet been thoroughly researched.

The share of girls, particularly girls of color, in juvenile detention is growing—and perceptions matter. Previous research has shown, for instance, that girls are often placed into the system because in court they don’t conform to what is seen as typical feminine behavior—with anger or defiance often being a result of trauma they had faced in the past.

“If authorities in public systems view black girls as less innocent, less needing of protection, and generally more like adults, it appears likely that they would also view black girls as more culpable for their actions and, on that basis, punish them more harshly despite their status as children,” the Georgetown researchers say.