The close-up shot of Nyajime Guet’s cherubic cheeks are a victory for her family and the aid workers who brought her back from the brink. In the world of aid photography, it’s also a rarity.

The four-year-old’s story was part of a Unicef photographic series, “Saved in South Sudan.” Her recovery from a skeletal victim of famine to a bright smiling toddler is remarkable not only for the humanitarian disaster unfolding around her, but also for how her images challenge media stereotypes.

For nearly as long as the international news cycle has been in existence, the images of a gaunt child have been used to sound the alarm of crises in Africa and elsewhere. Poverty porn—the graphic images of suffering and human vulnerability, framed with the specific purpose of eliciting emotion—has had a damaging effect on the people it captures as well as the audiences who view it: creating a cycle of victimhood and compassion fatigue.

It worked in the 1980s, when Bob Geldof and a choir of pop stars sang their hearts out for the famine in Ethiopia, as slow motion images of skin and bones children beamed on the stage backdrop. Yet, in a world where victims in the developing world are able to tell their own stories through social media, the “fly in the eye” images are no longer being accepted as the single story. Just ask Geldof when the well-meaning pop star remixed his song in 2014 for the Ebola outbreak and was met with global backlash.

In October 2015, Nyajime was brought into a Juba clinic emaciated, bald patches on her head, dead eyes deep in her skull, and just one of 1.1 million children starving in South Sudan. Her vulnerability is given more nuance as the viewer sees her attached to a feeding tube, then a little stronger on a scale with a grinning aid worker, and significantly, in the embrace of her father. It’s a simple yet often ignored framing, to show the child in a context of love and support.

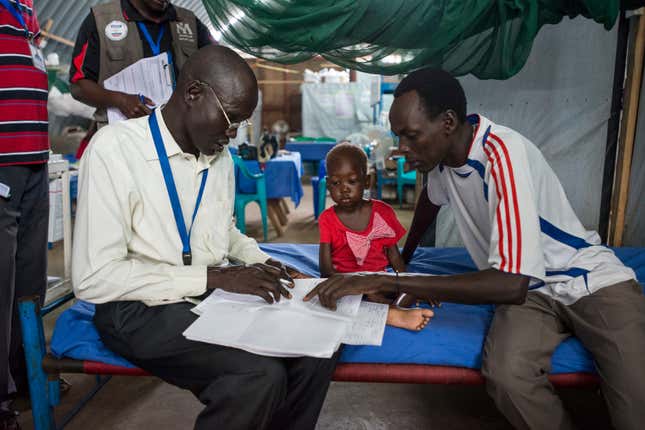

It’s what Chrisine Nesbitt Hills, Unicef’s senior photography editor, describes as a “purposeful narrative,” a personal story that creates a sense of empathy for a reader in their living rooms far away, while restoring the subjects’ dignity. This signifier could easily be created by showing a mother’s hand protectively wrapped around a child’s body, as the desperation of the situation is told through her small ribs poking through her skin.

“It also really shows how desperate the situation is because the mother cannot normally take care of her child for reasons like drought and conflict, the situation is out of her hands,” said Nesbitt.

Much has been done to dismantle these stereotypes, especially when it comes to the use of children’s images. Children have the right to accurate representation and dignity as part of their rights, according to the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Children, explains Nesbit Hills. Yet, as western governments consider cutting aid and viewers’ eyes glaze over these images, some aid agencies are slowly returning to those most desperate of images.

Right now the horn of Africa—South Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia—along with northern Nigeria and Yemen in the Middle East have been gripped by drought and a severe hunger crisis that is exacerbated by conflict. Unicef alone needs $251 million to deliver aid to children in the affected countries, the aid agency said.

At its worst, the crisis will affect 20 million people, according to the International Rescue Committee. And yet an average 15% of Americans know anything about it, according to a poll conducted by the the rescue committee. The poll went on to ask if those who knew about it would be moved to help, 73% said yes.

Stereotypes, however, have their advantages in split-second broadcast media or fast scrolling digital media. They create a familiar image that audiences by now understand as a cry for help. In truth, few audiences or media houses have the time to tell the whole story like Nyajime’s.

“An image of a starving child with flies in his eyes is cliched, but so is the image of a baby being rescued from the rubble of a collapsed building even though that is a positive image,” says James Oatway, an award-winning photographer who has just left South Sudan. “Both depict the realities of the situation on the ground.”

“It can be a difficult and messy area to negotiate,” said Oatway. “Audiences and editors definitely expect a certain type of image from humanitarian crises and there are plenty of cliched images to go around.”

Familiarity, and empathy, go along way in stirring people’s hearts and pockets to helping and, as Oatway pointed out, the situation on the ground is often harrowing. Empathy, as ethicists point out, could also restore the victims’ dignity with the simple question: what if it was your child?