Rwanda’s opposition candidates finally have a voice—but no real shot at the presidency

Kigali, Rwanda

Kigali, Rwanda

Diane Shima Rwigara, a 35-year-old accountant from Kigali, declared her presidential bid at a hotel in downtown Kigali. Seated alone behind a wooden desk, notes in front of her, she promised the usual—more jobs, less poverty, various reforms. Then she went a step further, pledging to give Rwandans a country free of intimidation and repression.

“What the ruling party has failed to deliver in 23 years, they can’t do in the next term,” she said. “Everybody is scared to express themselves because they are too scared of the ruling party. There is no freedom of expression in Rwanda.”

Two days later, nude photos of Rwigara were circulating the internet. A Ugandan newspaper featured barely censored images of Rwigara as its center-fold. Journalists called all day, asking if the photos were real while commentators speculated over whether she would have to drop out. Friends and acquaintances called to express their condolences, but Rwigara stopped answering her phone.

“I knew they would go low, but I didn’t know they would go that low,” Rwigara tells Quartz, sitting outside a friend’s apartment in a suburb of Kigali where her small campaign team had assembled for the day. She claims the photos were the work of the ruling party, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), but declined to provide any evidence. “It was done to discourage me, but it has not dissuaded me. It’s given me more determination,” she says.

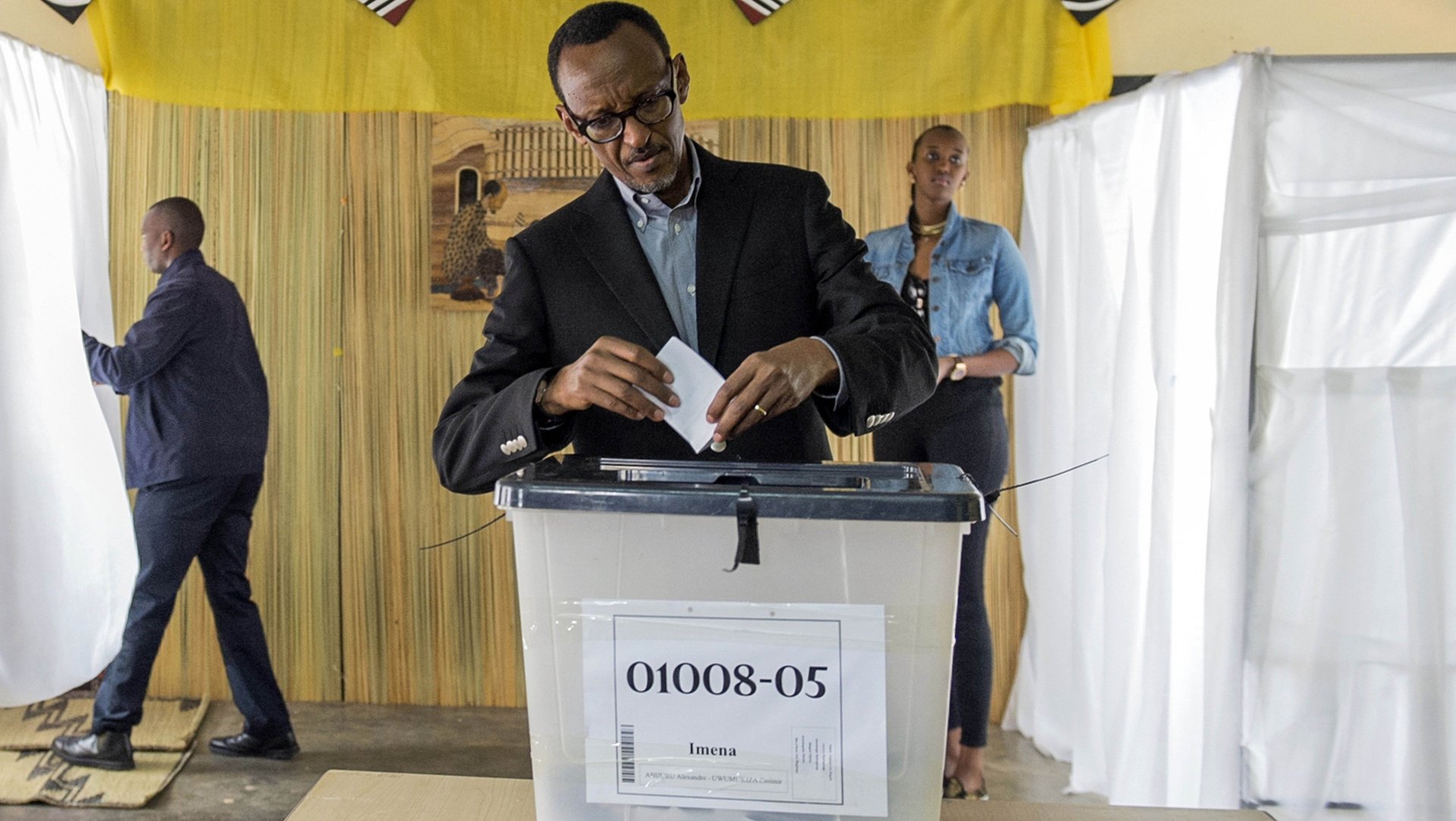

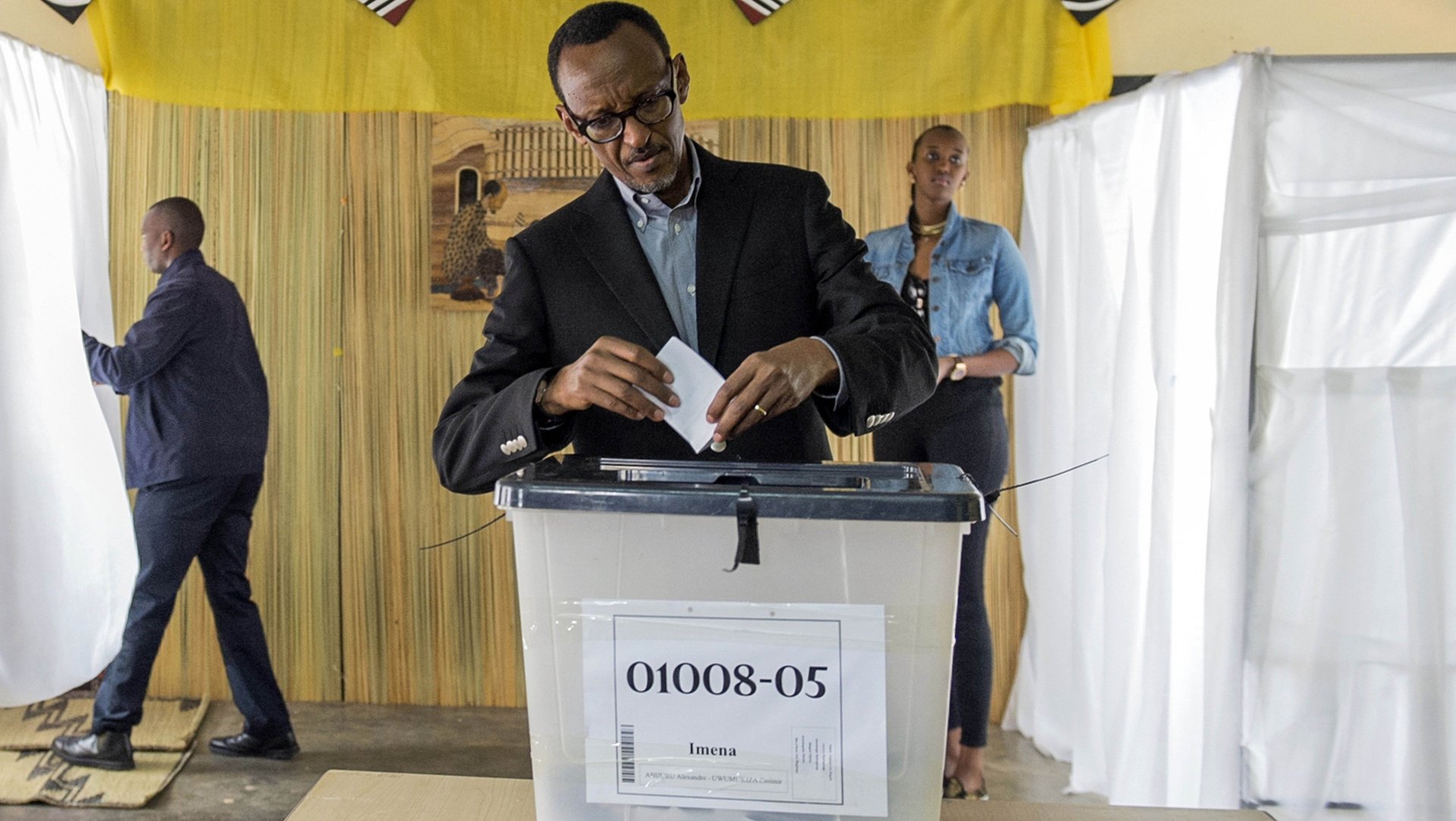

On July 7, election authorities release the final list of presidential candidates, including the Rwanda’s current president, Paul Kagame. Official campaigning will begin before the national elections is held on Aug. 4. It will be the country’s third multi-party presidential election since the 1994 genocide that killed 800,000 people, many of them Tutsis, a minority group to which the president belongs.

Since then, Rwanda has been dominated by one man and one party. Under Kagame and his party, the RPF, the country has been transformed into one of Africa’s most stable countries and least corrupt governments. It’s home to the highest proportion of women in parliament—61% of seats in its lower house are held by women—and a growing economy that makes use of drones, high speed internet installed across the country, and other “smart city” technologies.

On the other hand, critics say the calm Rwanda enjoys is that of a “repressive peace,” at the cost of civil liberties and truly competitive elections. Critics and rivals of the RPF have been known to disappear or wind up dead. An account of intimidation of media in Rwanda published last year includes a 12-page list of journalists who have been arrested, killed, or have disappeared over the last two decades. BBC in Kinyarwanda, the local language, has been blocked since 2014 after it aired a documentary questioning the government’s account of the 1994 genocide.

The election this year reflects some of Rwanda’s contradictions. Opposition figures in the past have been jailed or found dead—before elections in 2010, the vice president of the main opposition group, the Green party, was discovered beheaded, his body tossed in a river. Another opposition candidate from that election, Victoire Ingabire, is still in jail. Yet, so far Rwigara and other opposition candidates, have been openly criticizing the ruling party.

“It’s unprecedented in a way. She’s the first one to say openly how many Rwandans feel,” said a researcher focused on Rwanda, who asked not to be named for fear of intimidation upon returning to the country.

The space Rwigara has been allowed so far may have to do with her background. Rwigara, who studied finance and accounting in California before returning to Rwanda, is a Tutsi and from a family that once supported the RPF. Her father, one of Rwanda’s richest businessmen, died in 2015. She claims he was assassinated for resisting RPF demands related to his businesses ventures. The police say that he was killed instantly after being hit by a truck.

“You can go to prison for saying the wrong thing. You can be disappeared. You can lose your job, your business,” she says. “Foreigners say how they feel safe in Rwanda. We as Rwandans we do not feel safe.”

Frank Habineza, of the Green party, will be on the ballot after years of struggling to register the opposition party that he founded in 2009. He has also been openly criticizing longstanding RPF policies like an agricultural system that requires farmers to mono-crop and grow specific crops to sell to local cooperatives, rather than choose what to grow for themselves. The policy, aimed at ramping up agricultural production, has been criticized for hurting poorer farmers, and doing little to help food insecurity in parts of the country facing extreme drought. Habineza says that he would set apart public land for commercial farming.

“We have been calling for the opening of political space since 2009. It opens little by little, and now we have a real opening since I will on the ballot,” he says. “We are getting stronger.”

Other candidates are focused on poverty reduction and youth unemployment, which is around 23%, according to government statistics. While the government claims that 39% of the population lives beneath the poverty line, down from 45% in 2011, some researchers say poverty in Rwanda has actually increased since then.

“This is the beginning of freedom in Rwanda,” says Philippe Mpayimana, another opposition candidate. Mpayimana, a journalist, had been living in France until 2012 when he moved back to Rwanda. “It’s the first time that an opponent can speak freely,” he said.

But Mpayimana isn’t completely right. Election officials issued rules requiring any candidate campaigning on social media to submit all content to authorities 48 hours beforehand for approval. (The election commission reversed the decision early this month.) In May, a member of a banned political party, the United Democratic Forces (FDU) was found dead, with his head nearly severed off. The party claims the killing was a political assassination.

The candidates say they’re dealing with indirect forms of intimidation. A close friend of Rwigara’s disappeared around the time she wanted to announce her candidacy, causing her to delay several months. Habineza says members of his staff have been denied healthcare and supporters of his party have had their cows and other property seized. He himself gets strange phone calls and is accosted by strangers mocking him for attempting to run against Kagame. Mpayimana says friends and family members have distanced themselves from him.

“Yes, they do this kind of harassment,” Habineza says. “It’s a starting process. I think if we push on, maybe things will be better.”

Still, there’s almost no real opposition to the president’s reelection. All of other parties have declared their support for Kagame, and opposition candidates like Rwigara still face an uphill battle. Habineza’s Green party was only able to register in 2013. Mpayimana and Rwigara, who are running as independent candidates, were not on a recently released provisional list of candidates approved to run. They have until July 3 to fulfill the remaining requirements.

Most observers see Kagame’s win as a foregone conclusion, cemented in 2015 during a referendum on whether to amend the constitution to allow him more time in office. By voting for amendment, many Rwandans have already cast their ballot for Kagame’s reelection. European election monitors have decided not to come to Rwanda, in part because the election is so uncontested. Kagame, whose term would have ended at the end of this year, could potentially stay in office until 2034. He already ranks among the 10 longest-serving leaders in Africa.

In a way, the election also represents Rwanda’s path toward being a democracy in name only. ”What you’re looking at is not just the consolidation of the party but the consolidation of Kagame as president,” says Phil Clarke, who specializes in conflict issues in Africa at SOAS University London.

For Rwigara, the value of running may be more about speaking up than actually vying for the presidency. Asked what she thinks sets her apart as a candidate, Rwigara thinks for a second. ”I understand what it’s like to be a victim, how the government reduces you to silence,” she says. ”The question becomes either choose to live like a robot, being told what to say and what to do, or you take risks.”