Rwanda’s longtime president, Paul Kagame, inspires deeply polarized views. While some opponents and human rights activists criticize his rule, accusing him of rights violations and a strong-arm approach; others praise him for rebuilding the country after the 1994 genocide, and see the sense in him serving a third term, despite already being in power for 22 years.

Now, a book about Rwanda is illustrating similar competing views—this time, over the state of the east African country’s media environment.

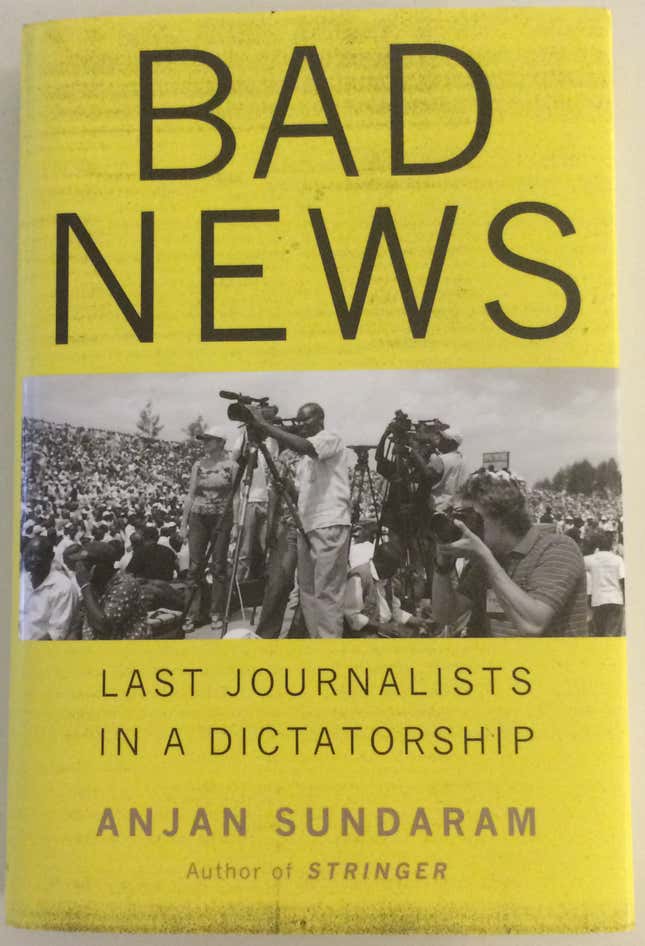

Journalist Anjan Sundaram’s recent book Bad News: Last Journalists in a Dictatorship, offers a sobering view of the end of independent journalism in Rwanda. Sundaram, who reported from central Africa for The New York Times and The Associated Press, spent four years in Rwanda training journalists and filling his own notebooks with damning tales of journalists suffering censorship and threats.

The stories Sundaram tells reinforce the judgments of press freedom advocates like the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and Freedom House, which recently reported that independent Rwandan journalists “were frequently harassed, threatened, and arrested.”

CPJ has documented the killings of 17 journalists in Rwanda since 1993 and in a 2015 report wrote that while the country’s government is stable, it “continues to act ruthlessly against critics and opposition figures.” In June last year, the Rwandan government banned BBC broadcasts in the Kinyarwanda language after the news organization aired a documentary on the genocide, which ended 800,000 Rwandan lives. The documentary suggested the president was involved in a plane crash that sparked the killings, and more ethnic Hutus were killed than previously reported.

Sundaram arrived in Rwanda in 2009. His book opens with a bomb blast in the Rwandan capital of Kigali. With the instincts of a journalist, Sundaram rushed to the blast scene, but found all traces had been quickly wiped away.

Police on the scene insisted nothing had happened. There was no government statement, and news organizations never reported the blast—as well as others that followed.

“I was told ambulances had come—their sirens silent,” Sundaram writes. “But the road was now practically clean.”

It was through his training classes that Sundaram said he began to understand the conditions for local journalists. His book describes one student being beaten into a coma. Another with HIV suffered physical and psychological abuse. A student called “Gibson” lived in a constant state of paranoia until he was forced to flee Rwanda, Sundaram wrote.

The account has been described by Western media outlets as “courageous,” “important,” and a “potent celebration” of the determination of Rwanda’s journalists.

But back home, some Rwandan journalists lashed out, calling Sundaram’s criticisms of Rwanda’s media environment greatly exaggerated.

“Fabrications and Distortions” charged a Jan. 12 story in the Kigali-based newspaper The Rwanda Focus, published the same day as Sundaram’s book—and republished by sites like RwandaWire.com and AllAfrica.com (which has since deleted the story.)

A few days later, Gonzaga Muganwa, executive director of the Rwandan Journalists Association, dismissed Sundaram’s book as outdated in an online article for Kenyan weekly newspaper The East African. “The government has, over the years, done a lot to ensure that we have press freedom,” Muganwa wrote.

Sundaram’s book used aliases for the journalists he trained, but the author of the Rwanda Focus piece, Sam Nshimiyimana, claimed to be “Moses,” one of the central characters in the book who helped Sundaram connect with other Rwandan journalists and traveled with the author to visit a genocide memorial.

According to Nshimiyimana, students in Sundaram’s class were jailed on extortion charges—not for writing negative stories about the government, as the book describes. And Nshimiyimana said “Gibson” (Alphonse Nsabimana, according to the Rwanda Focus account) invented his story about wanting to flee Rwanda.

“I can only conclude they wanted to have a journalist refugee to fill the need for such in the planned book,” Nshimiyimana wrote. “And all Nsabimana wanted was a one-way ticket to anywhere in Europe or beyond.”

Asked to comment on the article’s allegations, Shyaka Kanuma, chief editor of The Rwanda Focus initially agreed to answer questions sent by email but did not respond to followup queries. A Rwandan government spokesperson declined to comment.

Sundaram wouldn’t confirm the identities of any of his students in a phone interview, but said he was not surprised by the criticism: “I think what they’re saying only strengthens my narrative that there is no space for dissenting narratives in Rwanda today,” he said, adding that none of his former students currently work as journalists.

During a phone interview in February, Muganwa said that during the time Sundaram worked in Rwanda, some local journalists actively opposed the government, leading to confrontation. Now, he said, “The situation has been much more calm,” with journalists remaining politically neutral and the government relaxing some restrictions.

“They report the facts as they are, as is expected of journalists,” he said. “We don’t have widespread anxiety with journalists.”

At public readings, Sundaram has responded to criticisms by pointing to the 12-page list published at the end of his book of Rwandan journalists who have been arrested, killed or have disappeared since Kagame took power.

Sundaram’s book ends in December 2013, four months after the Rwanda Media Commission [RMC] was established to remove the responsibility of media regulation from the government, and investigate cases of defamation, plagiarism and ethics, according to its website. But the commission itself has faced persecution, and its head, Fred Muvunyi, fled the country in July after criticizing the government for banning the BBC, according to CPJ Africa’s Kerry Paterson.

Muvunyi was quoted in The East African story about Bad News saying that while he did not endorse all of the book’s claims, “no critical reporting is allowed [in Rwanda], even if it has a basis.”

Rwanda’s press has had a troubled past, with Human Rights Watch and the International Criminal Court both citing the media’s role in encouraging violence during the genocide.

Paterson said Rwanda has since loosened some restrictions on journalists. Still, press freedom suffers from a “chilling effect,” she said; and a fear of persecution drives many to self-censor any critical reporting.

“What that tells you,” said Paterson, “is that the government is still very much trying to stay in control of what is or isn’t appropriate to be shared or said.”