A lesson in hubris from one of the greatest basketball coaches of all time

When Phil Jackson signed on as president of the Knicks, New York’s star-crossed basketball team, it looked like an inspired move. In retrospect, it’s a cautionary tale about the arrogance of great leaders.

When Phil Jackson signed on as president of the Knicks, New York’s star-crossed basketball team, it looked like an inspired move. In retrospect, it’s a cautionary tale about the arrogance of great leaders.

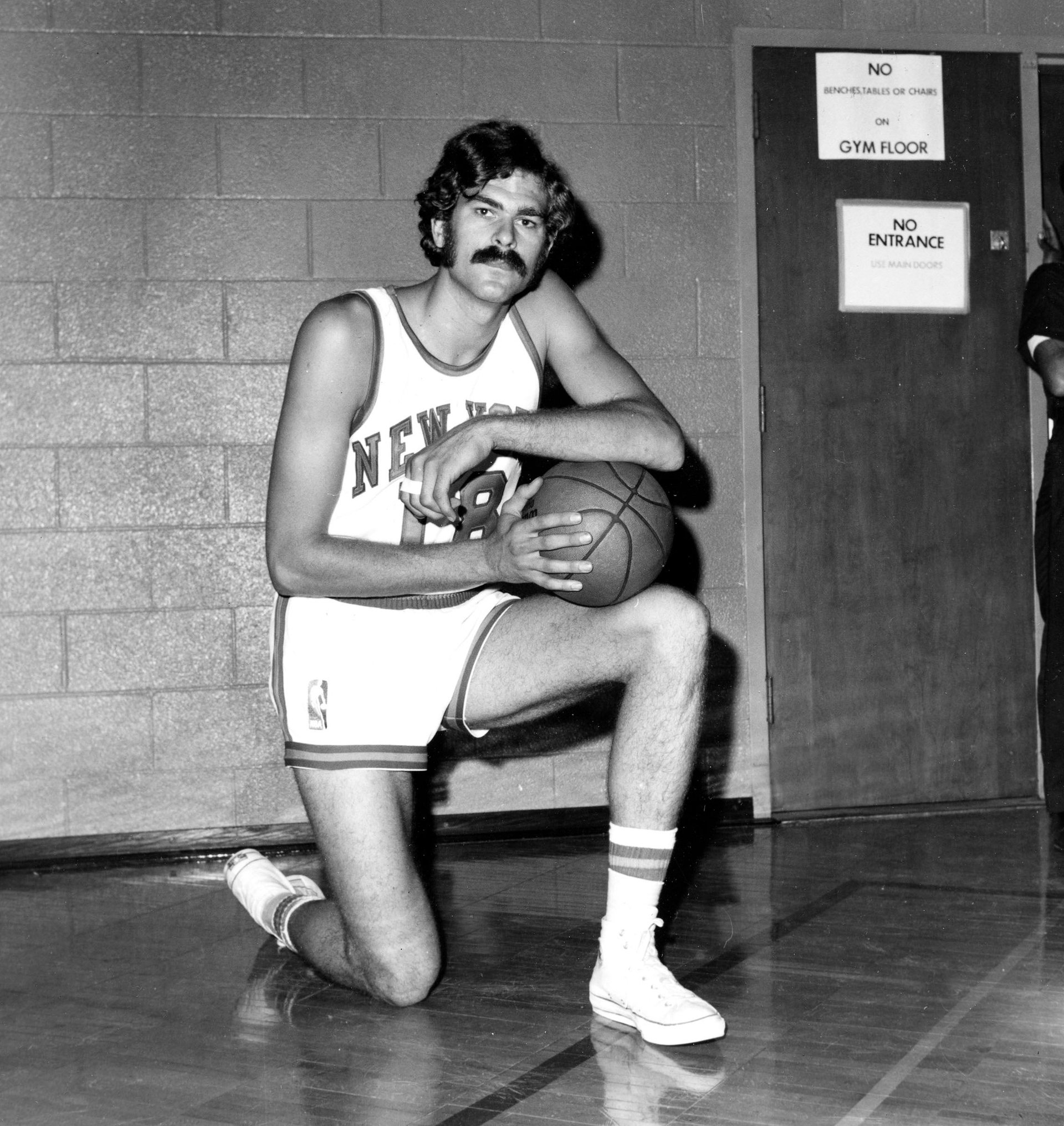

Jackson, 71, is one of the most successful coaches in NBA history, with six championships with the Chicago Bulls and another five with the LA Lakers. By taking on the Knicks, with whom he won two titles as a gangly forward in the 1970s, he could cap a legendary career by coming full circle, returning his former team to glory.

It didn’t work out that way. At all. Jackson was fired yesterday (June 28) after his teams produced a dismal 80-166 record over three years as he alienated star players and stained his otherwise sparkling resume.

Jackson made a critical mistake that has haunted other great leaders throughout history: Assuming success in one domain translates into success in another.

Coaching players is not the same as scouting them, and Jackson’s genius for motivating great players—he coached Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant to Hall of Fame careers— was of little use when it came to assembling a roster. Free agents who might have signed with Jackson the coach had no interest in playing for Jackson the president, and his choice of a former favorite player as a coach backfired.

From Ulysses S. Grant, who went from triumph as a Civil War general to ignominy as a failed US president, to Larry Summers, a successful US treasury secretary and disastrous president of Harvard (paywall), there’s a long line of managers who discovered their skill set was more limited than they realized.

Even when the next job seems like a logical extension, there’s no guarantee it will pay off. Michael Ovitz was the most feared agent in Hollywood, but his short-lived tenure as president of Disney was a catastrophe. Rob Johnson, a retailing star at Apple, failed at JC Penney, a very different sort of company. Rex Tillerson, one of the world’s most successful CEOs at ExxonMobil, appears lost as US secretary of state.

Of course, there’s plenty of examples of when switching professions works out. Dwight Eisenhower went from America’s greatest general to successful president. Steve Jobs was very good at running Apple, and very good at running Pixar. There are other NBA coaches who successfully transitioned to general manager, most notably Red Auerbach, who led the Boston Celtics to nine titles from the sidelines in the 1960s, and built three championship teams in the 1980s.

But as coach, Auerbach helped assemble his roster and so had developed the skills he needed to run the team. As a Celtic employee for 57 years, he was also deeply invested in the organization’s success. For all his skills as a coach, Jackson was handed teams with more or less complete rosters (Michael Jordan was drafted by the Bulls before Jackson came on board, for example). Jackson also seemed to have had little stake in the Knicks’ success. He was lured out of retirement by a $12 million-a-year salary, and his commitment to the project was questionable: He was rumored to have fallen asleep at player workouts.

No one ever questioned Jackson’s energy as a player or coach, but by the time he took the Knicks job, it seems he no longer had much to give. For great leaders tempted into second or third acts, retirement is often the better option.