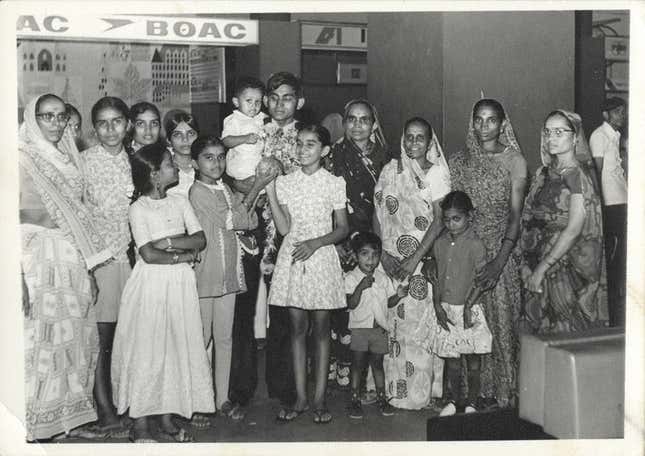

When he was 23, Mafat Patel headed for America. It was 1968, and he had just received a visa to get his MBA at Indiana University.

This trip would mark his first time outside his home country of India. Born the eldest of six siblings, three sisters and two brothers, he’d spent most of his life on a farm in the village of Bhandu, nestled in the Mehsana district of the state of Gujarat. He’d never traveled beyond the neighboring district of Patan, where he went to school to get his degree in Mechanical Engineering.

He completed his business degree within two years and moved to Chicago, where he fell into a vocation most other recent male South Asian transplants had, working the assembly lines of factories as a quality control engineer. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 had done its fair share to usher in an influx of educated immigrant minds who could turn into a skilled workforce.

But Mafat would later admit he found this work somewhat isolating. This bloomed into a unique quarter-life crisis: Though Mafat was surrounded by a number of recent immigrants like him, he still found himself unable to make America feel like somewhere he belonged.

It was an issue of appetite, mostly. His meals were the places where this alienation became most stark, dinners like small marches of misery, with American flavors he found difficult to find comfort in—nothing like the khichdi or curries he had grown up eating. Where was rice flour? Turmeric? This was an era in which Indians had to stuff canisters of these ingredients inside their checked luggage.

Mafat began to notice that others in this demographic subset had similar feelings; they were young Gujarati men like him, far from home for the first time, knowing they couldn’t forfeit their American livelihoods but still in search of any conduit to India. He took small solace in the fact that he wasn’t alone, and began to wonder what he could do to solve this problem.

Mafat saw a potential profit in this loss. He wanted to open a grocery store. It’d be small, but it’d have everything he, along with those in his community afflicted by his same pain, may need to cook the dishes from back home. And it showed signs of falling into place: In 1971, Ramesh Trivedi, an enterprising businessman, approached Mafat about a storefront on Devon Avenue that he wanted to sell, some shanty edifice that suffered from poor insulation.

Mafat didn’t mind. He dropped everything.

———

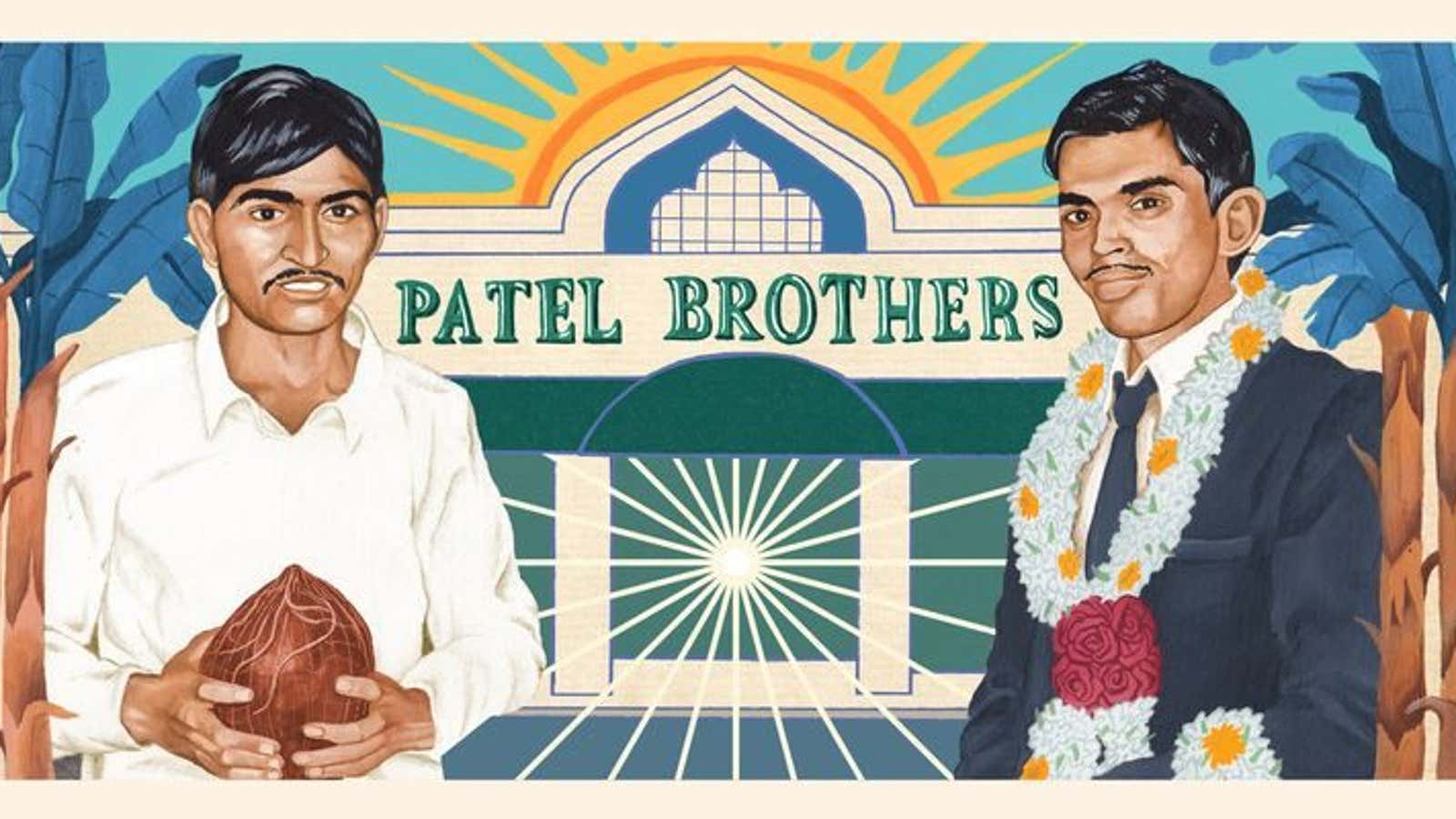

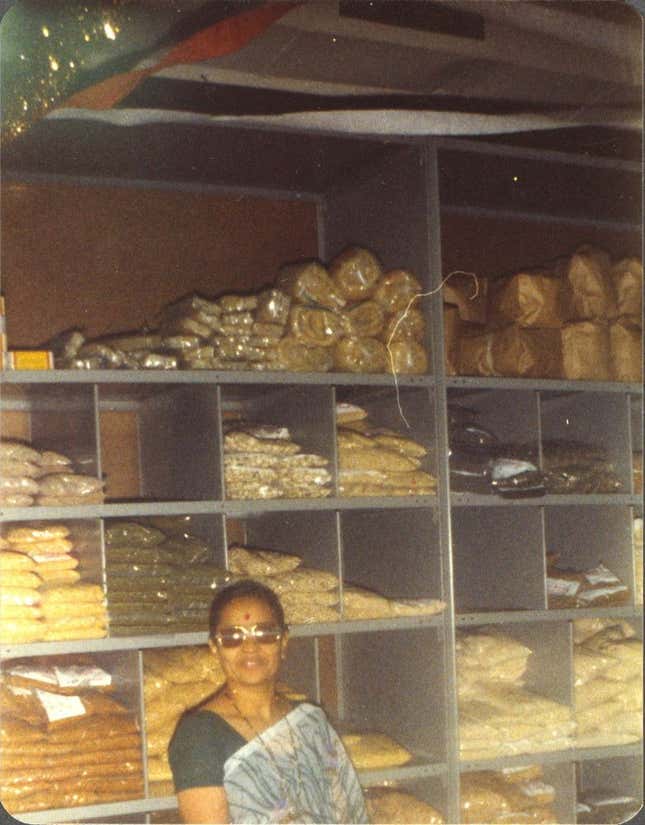

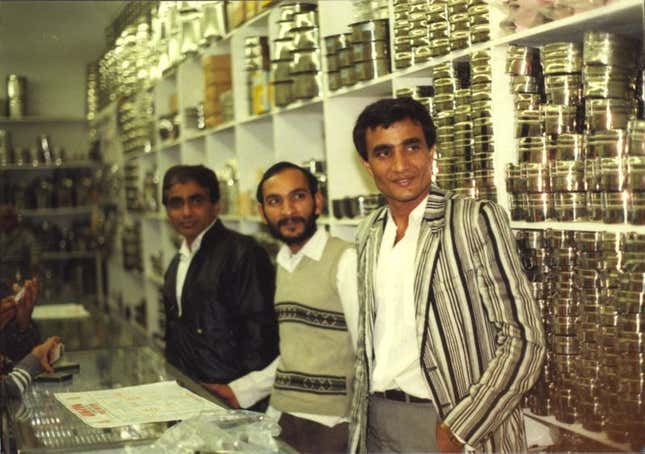

He quickly realized it was nearly impossible to mount a full-blown grocery store alone. So he asked his brother, Tulsi, still in Gujarat, for help. Though Tulsi and his wife, Aruna, made the pilgrimage to Chicago in 1971 just to aid Mafat in this undertaking, it took three years for them to sort out the logistics and open the first Patel Brothers store in September of 1974. It began as a modest operation, a sparse, dingy 900-square foot store with little in the way of anatomical logic. Shelves were disorganized and cluttered, while the then-three family members, the store’s sole staffers, traded shifts between 9am and 9pm; on their off-hours, the men would go to their second jobs.

Today, Patel Brothers has splintered into an $140-million emporium. On that stretch of Devon Avenue in Chicago alone, there is now Patel Air Tours, a travel agency; Sahil, a clothing boutique meant for Indian weddings; Patel Handicrafts and Utensils, which sells religious memorabilia and trinkets; and Patel Café, an eatery. Today, the stores are managed by a rotating cast of family members that stretches over three generations. The establishments are patronized by a motley of ethnic groups beyond the South Asian diaspora. Patel Brothers has 51 locations, most concentrated along the East Coast, some stretching to Texas and the American South, and one in California. The franchise has proven resilient throughout the ebbs and flows of the American economy.

“The most novel aspect of Patel Brothers is how accessible it has made Indian ingredients for non-Indian customers,” Priya Krishna wrote in a short paean to the chain a few months ago. She notes the store’s skillful ability to market itself to an America beyond the South Asian diaspora through a technique as straightforward as listing its ingredients in both Hindi and English.

Patel Brothers is a store that exists at the juncture of pragmatism and fantasy; the store has realized a possibility for pluralist cultural exchange without sacrificing its Indian DNA. Patel Brothers has spawned a subgenre of Indian grocery stores, from Subzi Mandi to Patidar Supermarket, yet it towers over this ecosystem like a citadel of the Indian-American grocery chain.

The brothers’ narrative is what we call American Dream, that story of the hard-working, industrious immigrant who proves his worth through serving others, defying preordained odds and obliterating those obstacles for others who follow. I contacted the Patel family multiple times for the purposes of this story, and was met, effectively, with the same response each time: They were just too busy to field my questions. Running an empire takes work.

———

It is funny to think that the existence of Patel Brothers owes itself to a matter as mundane as one man seeking relief for a deep human impulse: his hunger. Had I known of the store’s origins growing up in New Jersey, perhaps I would not have taken its very existence for granted. I must have been three or so when I first visited Patel Brothers. It became a permanent fixture of my childhood, so much that it never occurred to me that there was anything vaguely special, or revolutionary, about this store’s being.

This was the mid-90s. By then, the store had expanded to such cities as New York, Houston, Atlanta, and Detroit, due to the brothers’ realization that Indian families from various neighboring states were driving to Devon Avenue on weekends just to shop there. As I grew up, I saw my local store’s interiors gain more order and take on the characteristics of its larger, more mainstream competitors.

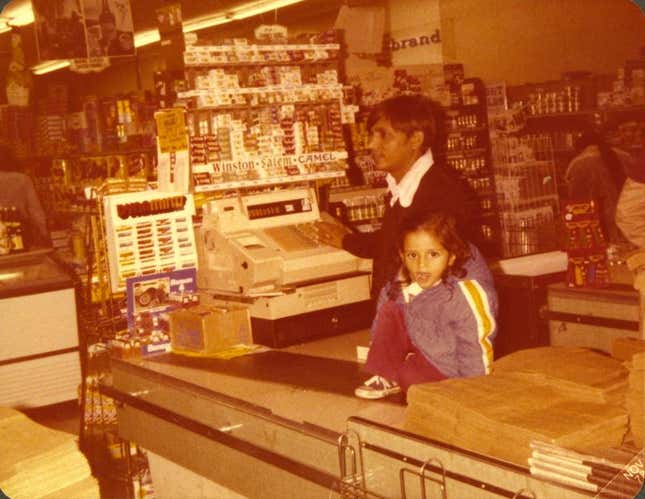

Swetal Patel, Mafat’s son, came of age in a family of ten in Chicago, with few students at school who looked like him. He spent a lot of time in the store as a kid, bagging groceries and pulling shopping carts from sidewalks to customers’ cars. Though he loved his mother’s cooking, he was too humiliated to bring any foods with some markedly alien odor with him to school.

“It was hard growing up, where we growing up in Skokie,” Susan Patel, Tulsi’s daughter, admitted in a 2013 interview. “I was one of very few Asians at the time in my school.” She had an experience similar to that of her cousin: The enclave of Skokie she inhabited was saturated with white and Jewish kids, and with it came an element of insecurity in her heritage. It didn’t quite help that the business of Patel Brothers surrounded her growing up, so much that it swallowed her adolescence. She’d help her father weigh grains after school and play tag in the store aisles as a way to pass time.

Having a childhood defined by her proximity to the store, a dynastic heirloom she didn’t ask for, occasionally overwhelmed Susan. Like her cousin, the pain stung doubly when Susan encountered an outside world that could feel harsh, incurious, or judgmental of her family’s Indian food. Everything she was told to question or suppress about her own heritage was refracted in her father’s store.

What changed? In the early 1990s, Swetal and his brother, Rakesh, both decided to put their degrees in Finance and Marketing to use. Rakesh recognized that there was a new generation of Indian-Americans now experiencing a clamoring much like that of their predecessors who’d come to the States from India: They were working long hours, and they missed their parents’ food.

In 1991, the pair launched a subsidiary of the Patel brand called Raja Foods, a response to the beckoning call for more pre-packaged Indian foods that could be heat up as easily as TV dinners: ready-made chapatis, pea-and-potato samosas, meals that resembled TV dinners, but with paneers. It had grown out of Rakesh’s senior thesis, wherein he devised a distribution company that could fulfill this very need. He decided to name it after his childhood nickname, Raja.

Susan was a bit more resistant to dedicating her life to the family business: It wasn’t until she went to college that she began to take an interest in her own culture, studying abroad for two semesters in India. The visit made her reconstitute her understanding of this store’s service to her family. She took the reins of Patel Handicrafts and Utensils in her early 30s. This business, once a source of turmoil and grievance, became a site of reconciliation.

———

Albeit a few decades younger than them, I grew up in a similar America to these second-generation Patels; I yoked my family’s foods to shame. I was a child of the Jersey suburbs, where I became profoundly distrustful of the outside world, believing onlookers would to write them off instead as evidence of belonging to a subspecies, that they would find the store’s delicacies—from kulfi to kachori, those fine-flour pockets filled with dal and fried until they pop like pockmarks—grotesque. As a kid, I would fib that my favorite cookies were Keebler’s El Fudge rather than Bourbon, with dark chocolate buttercream sandwiched between two biscuits topped with sugar.

I would come to see Patel Brothers as the source for the great shame I carried with me in public: A visit to the store could carry with it associations of everything I was instructed to despise, from a certain scent that clings to my clothes to a box of mango juice that didn’t look a thing like Capri Sun. It became tempting to disown even the simplest of pleasures, condiments like spiced tomato Maggi sauce, the more astringent sister to Heinz Ketchup, to consciously distance myself from them outside the safety of my own home. I played it safe, associating myself with these snacks’ more favorable American analogs.

Going to Patel Brothers became a sort of utilitarian pastime for my family, yet my mind engaged in its own, cruel form of trivialization as I grew older, seeing it as the sorry sister to ShopRite, A&P, or Pathmark. These were “American” stores my mind coded as white and thus aspirational. I carried this mindset with me for years until I moved from the East Coast to California for college, where there is one Patel Brothers store, in Santa Clara, a forty-minute drive from where my campus was. My diet had dulled in those years, revolving mostly around platefuls of quinoa, which I’d never consumed before college. Perhaps as an overcorrection for my ignorance, I ate quinoa as much as I could. It was a remarkably boring diet.

But there was an aspect of social performance to this, my attraction to dishes that gave me sustenance without the requisite gratification. It gave me the chance to deflect from any criticism that my palate still existed in the amber of my backward, brown childhood, that I hadn’t grown up yet.

My appetite for the foods I could find inside Patel Brothers became bottomless in that period, though in private. I craved chana chor, a spiced, fried chickpea snack that my parents and I mixed with Rice Krispies and had during tea in the afternoon. In the store’s absence, I grew weary for the thrills it offered.

When I returned home to New Jersey on vacations, I indulged in anything I could find on my visits to the store. I practically mainlined them when I got home. But I made a pact with myself to confine that experience to my parents’ place. I grew adamant about not bringing these snacks back on the plane with me.

It didn’t quite work. In my senior year, my parents stuffed a box full of soan papdi, flaky, cubelike clusters of besan (gram flour) and sugar, into my carry-on against my wishes. I was dreadfully embarrassed to have this on my person once I landed back on campus. Though I thought very briefly of putting it in the kitchen for everyone to share—I spent that year living in a house with nearly 40 other students—I wondered what they’d think, and I braced myself for the awful things they’d say when they saw its packaging.

Since there was no greater fear than not being liked, where did that leave me? I took my box of soan papdi with me into my room and kept it there, until I realized there were four other South Asians living in that house that year. I decided to share it with them. We reveled in its delights, careful not to reveal them to anyone else, because we were scared of what others might say.

We are taught to be ashamed of our appetites. We are told to actively suppress our hunger when it becomes too large. Distance made me understand that keeping these longings private was unsustainable if I wanted to be a functional adult. Spending time apart from Patel Brothers provoked a rigorous self-examination about what this store meant to me, and the first step was to acknowledge that it meant anything at all.

After college, I moved back East, a train ride away from my hometown. In this migration, I had undergone a mental maturation, finding permission to love the foods I had, thus prior, eaten only in solitude. I could put my cravings on display.

———

A visit to Patel Brothers can feel like emerging from a plane: Your sense of the world becomes radically slower, the activity of grocery shopping gaining a more leisurely glean than the frantic stress that can ordinarily accompany a trip to the supermarket.

One soggy Saturday in April, I trekked to the Patel Brothers in Edison, the one I remember most fondly from childhood. I hadn’t been there in months, because I hadn’t given myself much reason to be there lately, but my family found ourselves in the area. As I wandered the aisles, arranged like banks of baby mangoes and jackfruits, I was blanketed by dialects that were distinctly South Asian.

We go to the supermarket to get what we need. But our needs are determined by who we are and how we feed our obsessions. At the grocery store, everything we’d ever want is presented to us matter-of-factly, and we are forced to confront the extent of our desires. Our needs are not simply material. These are selfish, soulful wants, and they come from pits deeper than our stomachs.

I have lived in a world without Patel Brothers, so I can say this much definitively: It’s terrifying to imagine a world where this store does not exist. Here is a business venture born out of one man’s hankering for home and his family’s willingness to ease it. How comforting that they were brave enough to wield these desires openly, so that the rest of us could satisfy the hungers we don’t always realize we have.

I left the store with very little from that visit, drawn to what had long been my objects of affection: cake rusks for dipping in tea, a packet of wheaty and flat-baked Parle-G biscuits, and bag of frozen spinach-paneer samosas. These were items that others may characterize as inessential, but I needed them.

This post first appeared on Food52.com. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.

Celeste Byers is an illustrator in California. All photographs of the Patel family courtesy the South Asian American Digital Archive and Susan Patel and as sourced by Food52. Mayukh Sen is a staff writer at Food52.