Fireworks perfectly demonstrate a principle you can use to improve your life

Pyrotechnics may not seem like the stuff of philosophical discussion, given that they are loud and bright and designed to delight in spectacularly simple ways. But the dramatic fireworks demonstrations we use to mark celebrations—and their less friendly counterparts, rocket weaponry—were invented by ancient philosophers. They offer a profound lesson you can apply to hone your thinking skills.

Pyrotechnics may not seem like the stuff of philosophical discussion, given that they are loud and bright and designed to delight in spectacularly simple ways. But the dramatic fireworks demonstrations we use to mark celebrations—and their less friendly counterparts, rocket weaponry—were invented by ancient philosophers. They offer a profound lesson you can apply to hone your thinking skills.

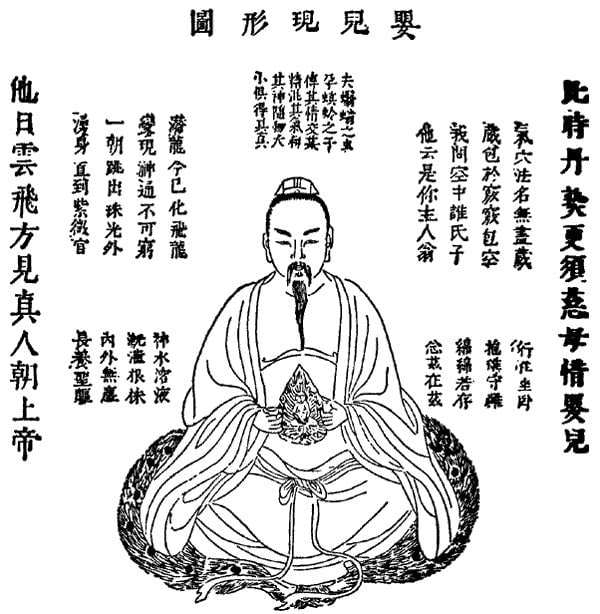

About 1,000 years ago, Taoist monks in China alighted upon the recipe for gunpowder—accidentally, it’s believed. These mystical scientist-philosophers actually were looking for long life, not attempting to develop weapons. Their invention took on a life of its own, and ended up being the perfect physical manifestation of a critical Taoist principle that things are not inherently good or bad—rather, it’s our approach that determines value.

Not born on the Fourth of July

Back in the day, when science and magic and mysticism were more or less one thing, people believed that that the key to long life might be found in alchemy. According to historian Jospeh Needham’s epic Science and Civilization in China, Taoist monks tried to manipulate the elements of nature, hoping to ultimately control time. They played with various chemical combinations in search of the elixir for longevity.

People and things were hurt in the process. The first written mention of gunpowder arises in the year 850 Chinese text Classified Essentials of the Mysterious Tao of the True Origins of Things. It states:

Some have heated together sulphur, realgar, and saltpeter with honey; smoke (and flames) result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house (where they were working) burned down.

The explosive reaction was considered by Taoists to be the result of combining yin, or feminine energy, and yang, or masculine energy. Manipulating these energies seemed key to longevity. So despite the dangers of playing with fire, experiments continued. Though the explosive combinations didn’t yield the desired result—the ability to manipulate time and life—it led to the creation of what scientists now consider to be the first propelled rockets, called “ground rats.”

The original ground rat was likely a tube of bamboo stuffed with gunpowder and held over a flame. When lit, it would splutter and explode, making sound and sparks. These firecrackers were quickly integrated into Chinese celebrations, as the loud sounds were thought to ward off evil sprits.

The explosive qualities were noted and developed and put to use in other contexts, too. Soon, experiments with prolonged life led to many violent deaths. The 1044 text Wujing Zongyao—known in English as the Collection of the Most Important Military Techniques—provided gunpowder recipes and information on making incendiary bombs, projectiles, and grenades.

The rest is, of course, history. The power of pyrotechnics became recognized internationally, and the experiment with long life has mostly turned into centuries of ever-more-sophisticated science and violence. Taoist monks who accidentally invented gunpowder would not be surprised.

The explosive truth of the quiet mind

According to the sage Lao Tzu, who is said to have dictated the Tao Te Ching in the 4th century BC, there are no absolutes. There’s no black and white, only shades of gray and constant change. He wisely described just the sort of thing that happened with firecrackers long in advance of their development, providing:

It is on disaster that good fortune perches

It is beneath good fortune that disaster crouches

Who knows the limit? Does not the straightforward exist?

The straightforward changes again into the crafty, and the good changes again into the monstrous.

Lao Tzu’s simple observation that nothing is simply one thing is the key to leading a more nuanced, thoughtful, and forgiving existence. When we see that people and things have multiple attributes and possibilities, rather than relegating them to stark and simplistic categories, we become sophisticated thinkers.

Approaching all ideas with nuance can be time consuming. It’s also incredibly useful. You stop assuming outcomes are understandable. You know that you cannot know, and that is where wisdom famously begins, according to the Greek philosopher Socrates.

As the accidental invention of gunpowder demonstrates, ideas have lives, intentions aren’t everything, consequences aren’t predictable, and nothing is just one thing. Only time will tell, and keep on telling. Because things change.

Keeping this in mind can transform your life, giving you and others room to grow. Assimilating the principle can make you more realistic, less picky, and less arrogant. You can apply it to ideas in science or politics or to personal things like how you face a day.

Seeing shades of gray doesn’t mean you lead a bland, undecided, wishy-washy existence in which you make no decisions. It provides the space to keep an open mind, sometimes change, or even occasionally remain undecided.

We live in opinionated times, and it’s tempting to chime in when everyone’s always tweeting explosively. Still, things are never what they seem and often much more complicated than we could ever imagine. So it’s fine—in fact, quite wise—to not know anything, even keep quiet. According to the Tao Te Ching, “Great skill seems awkward; Great eloquence seems tongue-tied.”

That’s just something to keep in mind during pyrotechnics, real or metaphorical.