“Murder without spilling blood”: the Chinese Communist Party’s history of denying medical treatment to its enemies

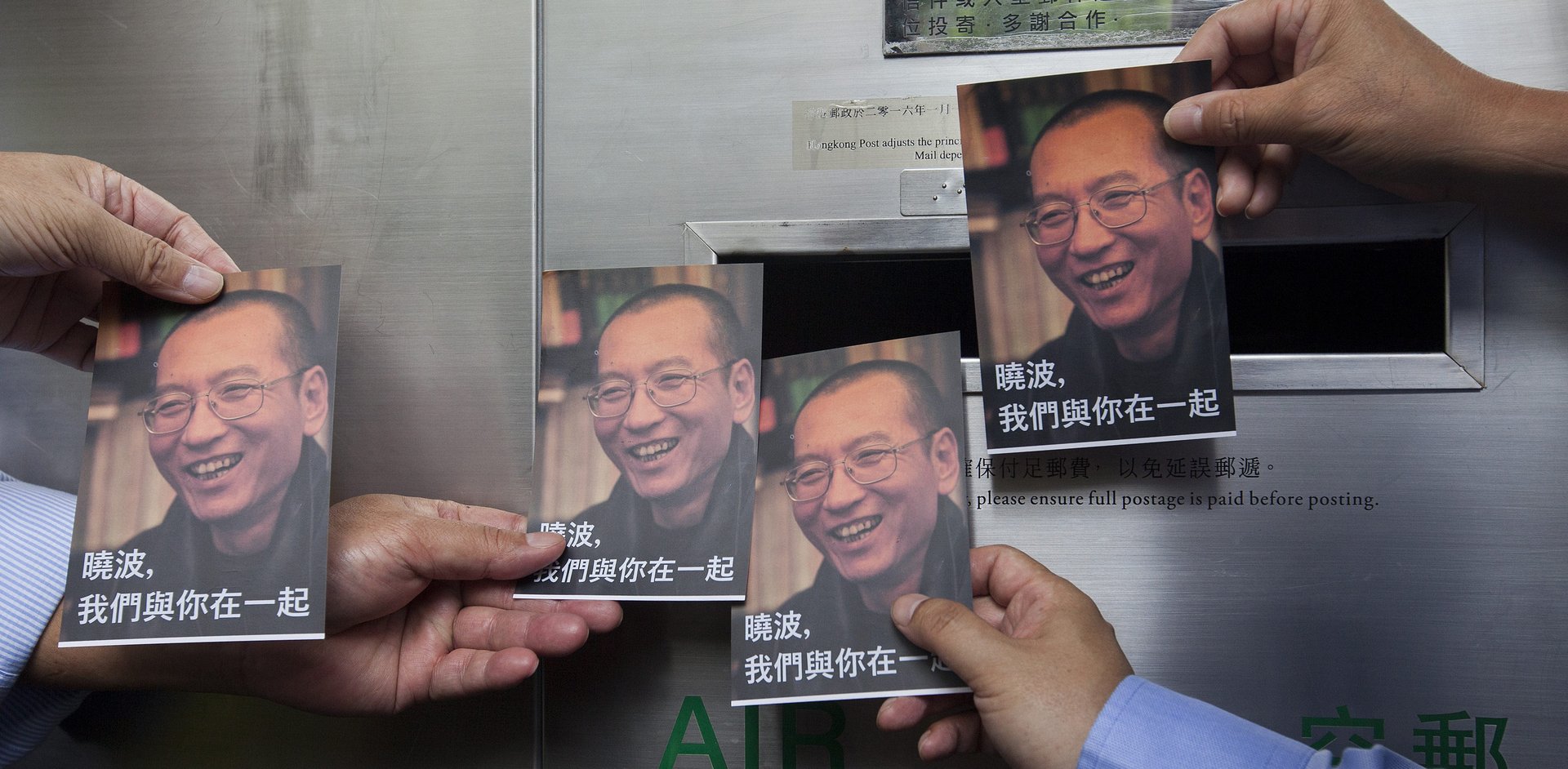

When news emerged that Nobel Prize winner Liu Xiaobo was gravely ill in hospital with late-term liver cancer, many wondered whether the Chinese Communist Party had purposely delayed treatment for the vocal critic of the regime.

When news emerged that Nobel Prize winner Liu Xiaobo was gravely ill in hospital with late-term liver cancer, many wondered whether the Chinese Communist Party had purposely delayed treatment for the vocal critic of the regime.

Indeed, the party has a history of intentionally denying or delaying adequate medical treatment to such critics, or people deemed “enemies of the state.” During the era of chairman Mao Zedong, many of China’s intellectual elites were sent to labor camps and jails, where harsh conditions and the denial of health care often led to poor health and early death. Those who survived suffered from chronic illnesses and mental trauma that lasted for the rest of their lives.

Veteran journalist Dai Huang, who was sent to labor camps for 20 years after being branded an “anti-party” element for criticizing Mao’s cult of personality, wrote in his memoir Nine Deaths and One Life of his own experience of starvation, injury, sickness, and denial of medical treatment. Dai, who died in 2016, also chronicled the brutal treatment of artists, academics, and journalists who perished in the camps.

Dai wrote that even when these political outcasts were sent to rural clinics, staff were often too afraid to treat them, wary of being accused of sympathizing with “class enemies.” When he suffered a serious leg injury in an accident, his supervisor accused him of faking illness. In his elderly years, Dai suffered from hepatitis and cancer of the colon and rectum, illnesses that his family attributed to malnutrition and harsh conditions in the camps.

The return of “class enemies”

Senior members of the Communist Party who were seen by Mao as a threat were not immune to such maltreatment. After president Liu Shaoqi was purged in 1967 during the Cultural Revolution, the one-time designated successor of Mao was put under house arrest and condemned as “a traitor to the revolution,” “enemy agent,” and China’s foremost “capitalist-roader.” According to historical accounts, he was frequently beaten in public denunciation sessions and was for a long time denied medication for diabetes and pneumonia. In October 1969 he was taken from Beijing to Henan province, where he died in isolation a month later.

He Long (link in Chinese), a military leader and vice premier, spent the last two-and-a-half years of his life under house arrest, where he was deprived of food and water, made to sleep on the floor with no blankets and pillows, and refused medication for his chronic diabetes. When he was finally sent to hospital, doctors were ordered not to give him the best medicine. He died in 1969, after a glucose injection caused complications for his diabetes. According to some reports, he condemned the authorities’ treatment as “murder without spilling blood.”

Tao Zhu, another top party leader who was put under house arrest during the Cultural Revolution, was diagnosed with cancer of the gall bladder but was refused medical treatment until it was too late, author Jung Chang chronicled in her book Wild Swans. He died in 1969.

With the launch of the “reform and opening up” era in the 1980s, the brutal class-based ideology of the party was in gradual decline, as Liu Xiaobo also noted—only to make a comeback in recent years under president Xi Jinping, as government critics languishing in custody with ill health died under suspicious circumstances.

Activist Cao Shunli died in hospital in March 2014, three weeks after she fell into a coma under unknown circumstances and was granted medical parole. She was detained by police six months earlier for staging protests on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” Her lawyer said she was denied treatment for tuberculosis and liver disease, and her family, denied visits while she was alive, said her body appeared bruised and swollen.

In July 2015, Tibetan monk Tenzin Delek Rinpoche died in a Chinese prison after having served 13 years on separatism and terror charges. His family applied for medical parole, citing a heart condition, but were ignored.

The rhetorical foundation of Xi’s increasingly repressive rule can be traced to a 2012 article (link in Chinese) in state mouthpiece People’s Daily, which cautioned against the danger of five categories of people—dissidents, rights lawyers, underground religious followers, opinion leaders on the internet, and the underprivileged—accusing them of “infiltrating” Chinese society to push for regime change. It was reminiscent of the so-called ”five black categories” of the Cultural Revolution—landlords, rich peasants and capitalists, counter-revolutionaries, “bad elements,” and rightists—who were often violently beaten up by Mao’s Red Guards and refused treatment by medical staff.

In critical condition

Since he was “released” on medical parole in June, Liu Xiaobo has been transferred to a hospital in the northeastern city of Shenyang. As Liu’s life hangs in the balance, Chinese authorities are pulling out all the stops to reject accusations that he has been denied adequate health care, in an apparent response to international criticism.

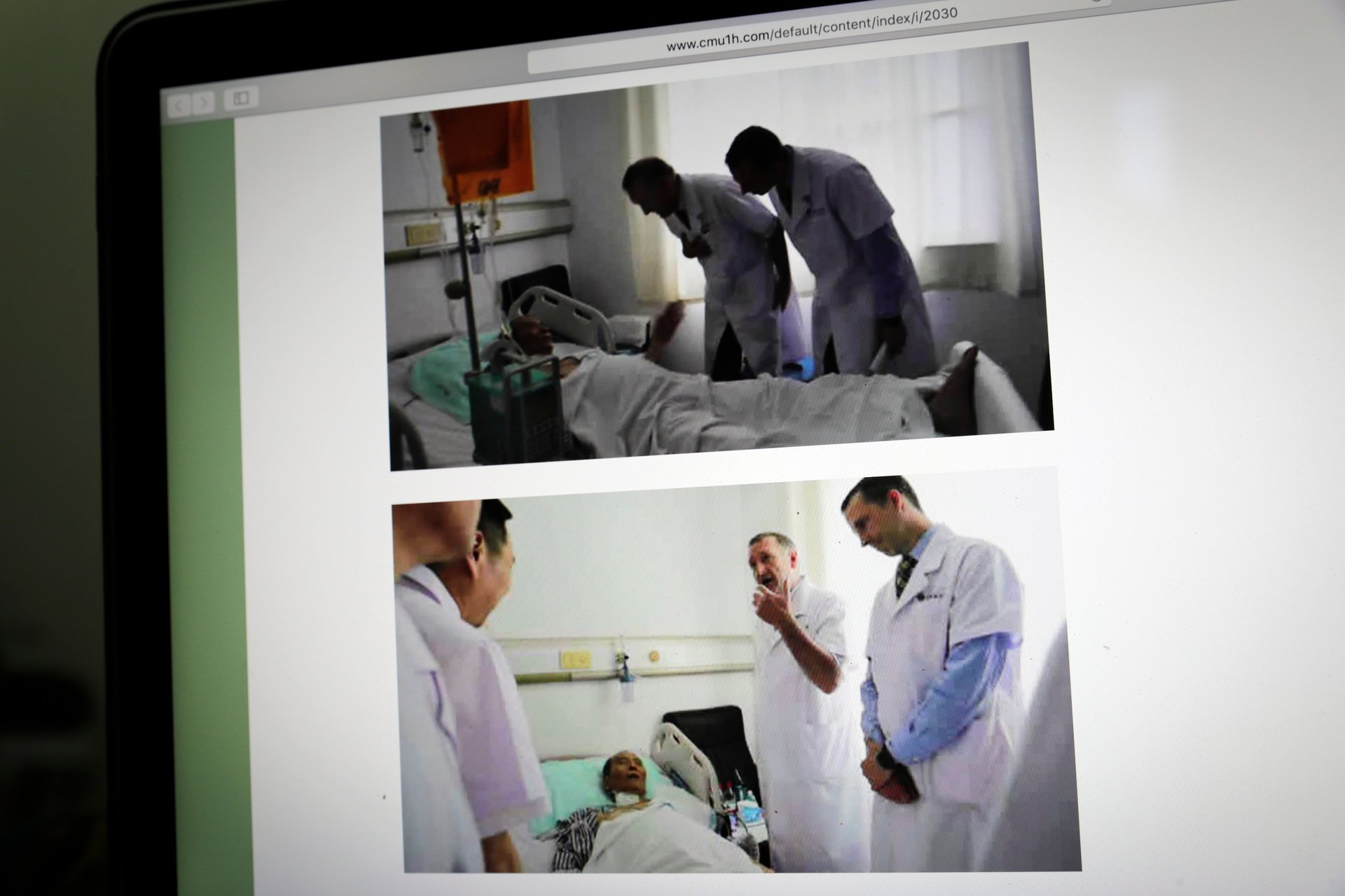

The government openly invited foreign doctors to treat Liu last week. Official websites say Liu has been undergoing annual health check-ups since he was jailed in 2009, and that Liu has been treated by the country’s top cancer expert since his cancer was diagnosed in early June. A video was posted on YouTube—which is blocked in China—showing Liu receiving medical treatment, including a scan, and captured him saying on camera that he “greatly appreciated” the care he was offered. Authorities also contend that Liu already had a history of hepatitis B before he was imprisoned this time round.

Yet Chinese authorities continue to deny him the freedom to be treated abroad. German and American doctors who visited Liu said they believed that he could travel, contrary to claims by the Chinese government.

In 2009, in his final statement to the court before his 11-year jail sentence was announced—which was also read out in the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo—Liu said he still held out hopes for his country. He said compared to his previous jail terms, he experienced more humane treatment during this period of incarceration, and said that was evidence of the decline of the Maoist philosophy of class struggle:

“The weakening of the enemy mentality (in Chinese society) has paved the way for the regime to gradually accept the universality of human rights… It is precisely because of such convictions and personal experience that I firmly believe that China’s political progress will not stop, and I, filled with optimism, look forward to the advent of a future free China.”

The First Hospital of China Medical University in Shenyang said on Monday (July 11) that Liu was in critical condition. A statement on the hospital website said his tumor has grown, and that there are other complications including bleeding from his liver, peritonitis, acute renal insufficiency, and a drop in blood pressure.

As he lies in the hospital in Shenyang, denied the chance to receive the best treatment abroad, Liu’s hopes of a free China die with him.