In China, internet censors are accidentally helping revive an invented “Martian” language

When Chinese social media users on microblog Weibo came across an almost illegible post earlier this month, many of them would have instantly recognized it as “Martian,” a coded language based on Chinese characters that was very popular many years ago.

When Chinese social media users on microblog Weibo came across an almost illegible post earlier this month, many of them would have instantly recognized it as “Martian,” a coded language based on Chinese characters that was very popular many years ago.

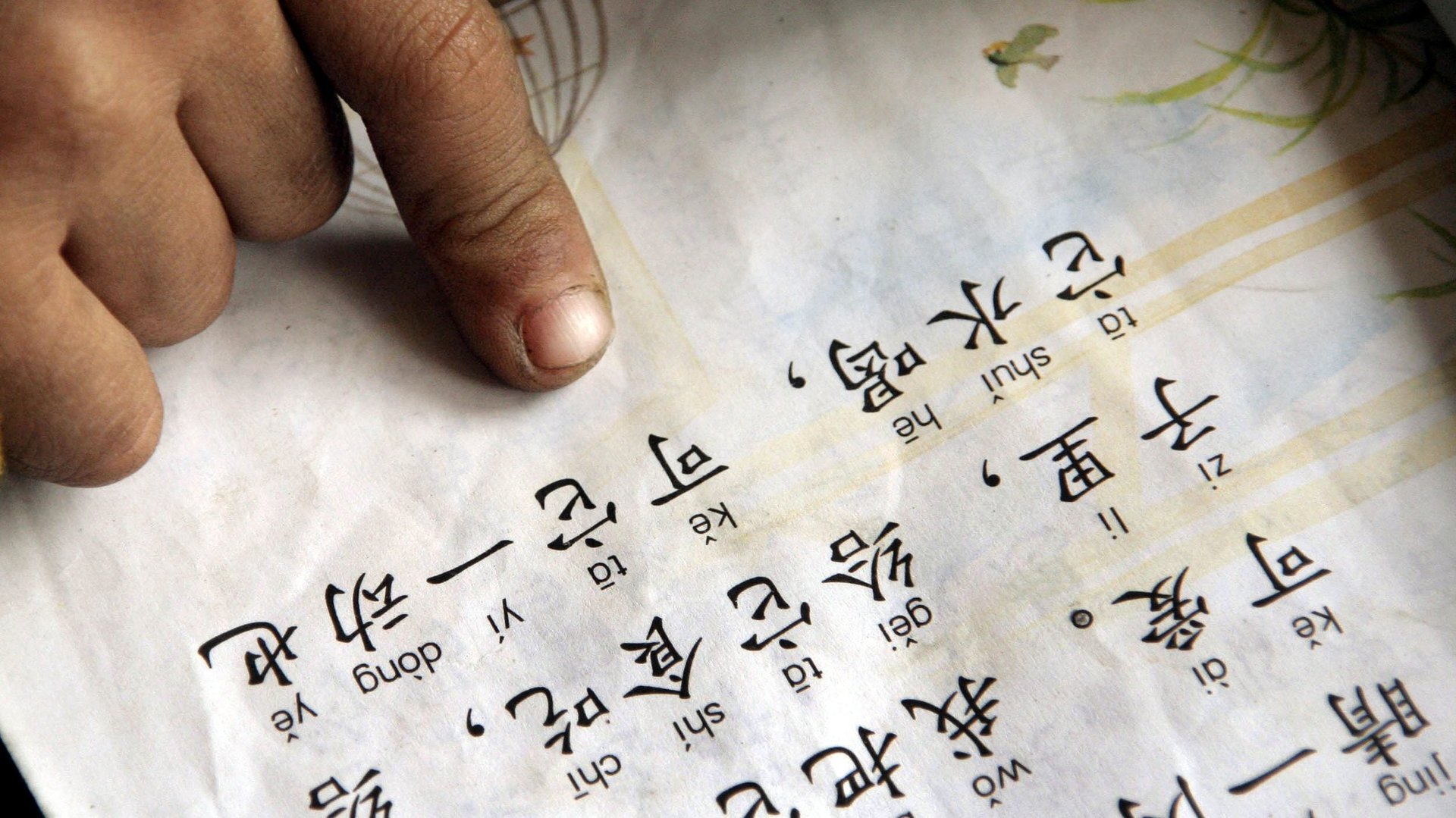

It was a version of a post by a prominent retired sociologist and sex adviser, Li Yinhe, in which she called for the elimination of censorship in China. The original post went viral on Weibo, which is similar to Twitter and has some 340 million monthly active users. More than 60,000 users (link in Chinese) shared the post—unsurprisingly, it was soon deleted.

Chinese internet users and media observers have noticed tightening online restrictions in recent months, as stricter internet rules for online journalism and a new cybersecurity law came into effect in June. This month, in the wake of the death of Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo in custody, pictures vanished from private conversations on messaging platform WeChat, and similar blocks were noticed on WhatsApp, the last product from Facebook available in the country, and hotels announced they were reconfiguring internet access to comply with Chinese law.

To navigate around restrictions, Chinese internet users have often engaged in linguistic acrobatics, from code words, slang, and coded images, to dipping into other languages. Recently, some have turned to Martian (huo xing wen), a linguistic invention from the early days of the Chinese-language internet that had fallen out of favor and now is resurfacing.

A brief history of Martian

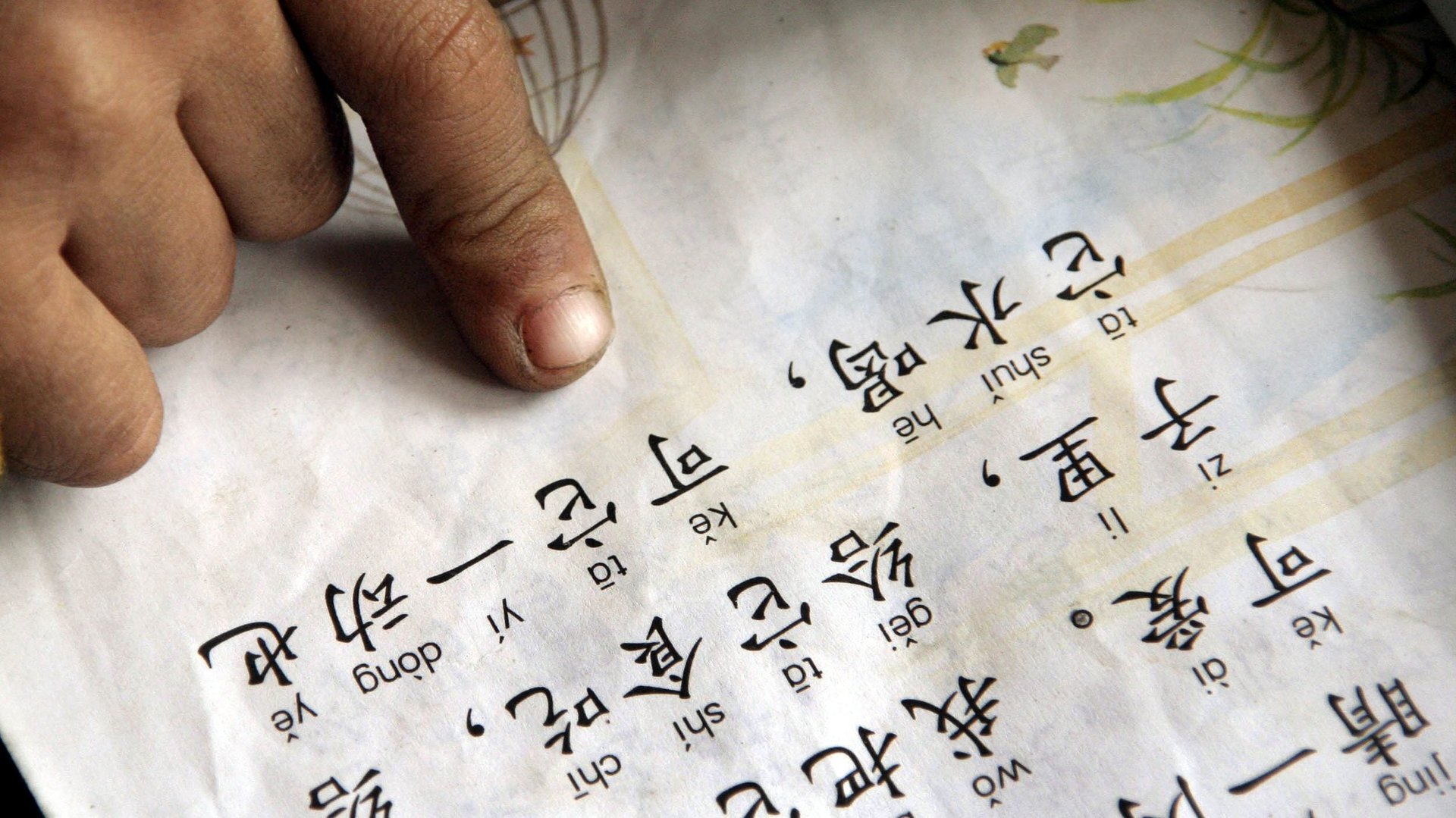

Martian dates back to at least 2004 but its origins are mysterious. Its use appears to have begun among young people in Taiwan for online chatting, and then it spread to the mainland. The characters randomly combine, split, and rebuild traditional Chinese characters, Japanese characters, pinyin, and sometimes English and kaomoji, a mixture of symbols that conveys an emotion (e.g. O(∩_∩)O: Happy). For example, the word “一个” (yī gè), which means “one of” or “one thing” is transformed into “①嗰” in Martian language. It replaces “一” with the number in a circle and adds a small square to the left of the traditional version of “个.”

A Weibo user who goes by the alias Tangnadeshuo, and is a Martian-language user, says it’s a marker for Chinese people born after 1990: “We use it to make fun and sneer. It’s a cultural symbol of the post-1990s [generation],” he said.

It’s not an easy language to master—the same Chinese character can have more than one Martian counterpart.

Even so, Martian language fever swept across the strait as players chatted in popular online games like Audition Online (link in Chinese) and then flooded onto Tencent QQ, a widely-used instant messaging app at the time. Soon creative Chinese developed new Martian language input methods for keyboards. The language has online translation tools.

“It was very popular back in my school days… People used Martian language in their ID and profile descriptions on QQ,” Lotus Ruan, a research fellow at University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, which conducts research on censorship, told Quartz.

Good for hiding from parents—and censors

Though it’s hard to read, young Chinese adopted the language not only because it was new and cool but also because it was incomprehensible to parents and teachers. Parents in paternalistic China seldom regard teenagers’ messages and diaries as their private materials. But they weren’t familiar with the transformation rules of Martian (and some even worried that using Martian might affect other language skills). Gossiping in Martian prevented many moms (link in Chinese) from understanding children’s messages in QQ and prevented teachers from reading notes passed to classmates.

“Although Martian language is not as popular now as it was five to 10 years ago, people will still resort to it from time to time to circumvent the censors,” Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Pennsylvania, told Quartz.

Internet censorship works by filtering information for sensitive keywords. Research by Citizen Lab’s Jason Q. Ng shows that a Weibo post will first be reviewed by a machine and flagged if it contains certain keywords that are blacklisted. Human censors also review published posts. Using Martian can prolong the longevity of a post. “If the Martian language [versions] of certain keywords are not on the blacklist already, it can be used to bypass censorship until a human reviewer censors it,” she said.

It isn’t only the Chinese who’ve resorted to using workarounds derived from Martian, such “7-1, 5-1” to refer to the June 4 Tiananmen Square protests (the math in the workaround refers to the date 6/4). In 2014 when the British Embassy in China published a 2013 human rights report, it posted (link in Chinese) the title in Martian: “2013人权和民主报告” was written as “2013人木又与MZ报告.” The new titl breaks down the word “权” (rights) into its two parts “木又,” replaces “和” with its synonym “与,” and changes “民主” (democracy) into the initials of its pinyin “MZ.”

In the face of renewed efforts to ban the use of individual VPNs and crack down on online video streaming services, Chinese netizens have become increasingly concerned about their ability to communicate online. Earlier this month, a Weibo user posted in Martian language (link in Chinese and Martian language): “From today on, I will post on Weibo in Martian language. Because if I post in Chinese I will be gagged. Guys you can have a try. “

It doesn’t always work every time

After the sexologist Li Yinhe’s anti-censorship July 9 post in Chinese was deleted in China—it can still be read outside China—it was reposted several times in Martian. Several of those posts got deleted too, most likely by a human censor, but one still survives.

Ruan notes that just because a Martian term gets blocked on one platform doesn’t mean it won’t be useful on another. “Internet users should also note that censorship in China is not monolithic,” she said. “If a Martian-language keyword is censored on Weibo it does not necessarily mean that it is censored on other platforms such as WeChat.”

Still, as China’s sensitive-terms blacklist gets refined, Martian language may become less helpful. Also Chinese Martian users trying to evade censorship shouldn’t ignore the possibility that, like them, people working in internet censorship groups might once have been Martian-speaking teens too.