It’s not easy being a pioneer. You make a big bet on your vision, make all kinds of personal sacrifices and when you succeed, you’re hailed as a hero. With that comes a lot of responsibility. The need to lead by example and accept that you’ll also be seen as the face of your community, whether you want to or not.

This brings us to Ushahidi and the Kenyan tech ecosystem. Ushahidi, is a social enterprise platform which was developed to map reports of violence in Kenya after the elections in 2008. It was a pioneer of Kenya’s much celebrated tech space and effectively also a leader in Africa’s startup ecosystem.

This week, after blog reports, the platform acknowledged a reported case of sexual harassment against a senior member of the Ushahidi team. The details and speculation around the case have been picked over on several African tech blogs, discussion boards, and various personal posts. The victim has since left the company and one person has been suspended while an investigation is ongoing.

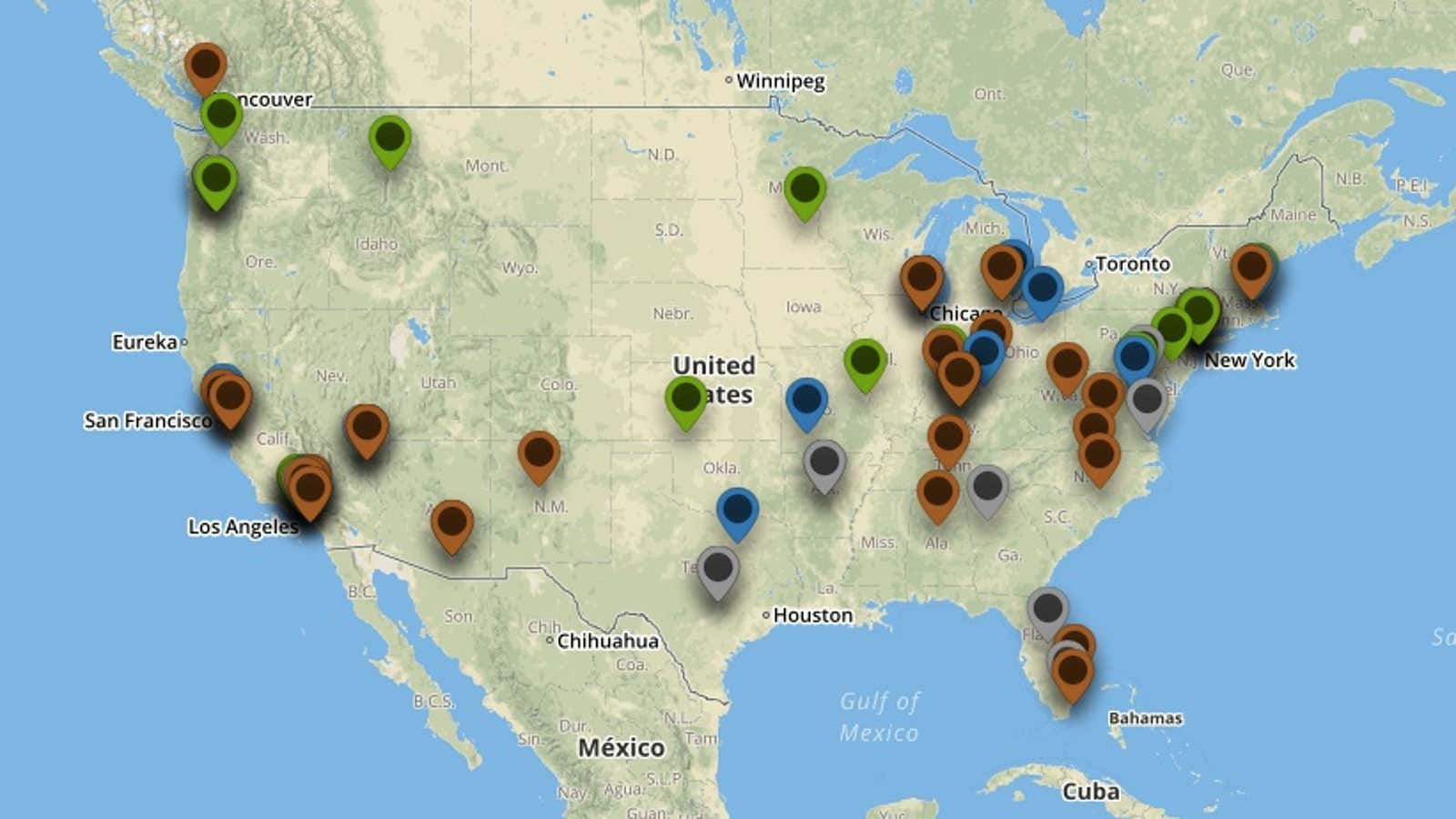

Most people are disappointed when sexual harassment happens anywhere but especially at one of the more progressive organizations, not just in Kenya or Africa, but in the wider tech world. Ushahidi literally means ‘testimony’ in Swahili. Its work has come to represent transparency and forthrightness; it’s been applied from Kenya to Venezuela to even the United States.

That’s why the biggest disappointment has been the poor handling of such a sensitive topic. The terse public statement, obfuscation, and foot-dragging (the allegations are at least two months old) say a lot about the way the organization is run. Ushahidi was co-founded by some of the leading lights of Nairobi’s tech scene including Juliana Rotich, Erik Hersman, Ory Okolloh, and David Kobia. Given what we’ve seen unravel on a much bigger scale in Silicon Valley, one would hope that lessons would have been learned.

Some worry the slow and reluctant reaction is meant to avoid dissuading future investment or support from future investors and partners. Ushahidi is already backed by the who’s who of social enterprise investment including Omidyar Investments, Google.org, the Ford Foundation, and several others.

This is not just about one harassment case but about a culture. This is an opportunity for Ushahidi’s board, advisors, and backers to do the right thing in a way that sends a message to the rest of the fledgling African tech community. What it does and how it does it, will have long-term ramifications.

As Okolloh, who left Ushahidi in 2010, says in her post: “The start-up ecosystem in Kenya is no longer nascent it can and must handle the hard work and tough conversations that will happen in the coming weeks and months. There is no otherwise.”