Jeff Bezos is out to crush Blue Apron

Blue Apron has an Amazon problem.

Blue Apron has an Amazon problem.

Two weeks before the meal-kit company debuted on the New York Stock Exchange, Amazon inked a deal to buy Whole Foods Market for $13.7 billion. One week after the IPO, Amazon Technologies, a subsidiary of Amazon.com, registered a trademark in the US for the phrase, “We do the prep. You be the chef.” A filing describes the trademark as for “prepared food kits composed of meat, poultry, fish, seafood, fruit, and/or vegetables and also including sauces or seasonings, ready for cooking and assembly as a meal.”

Last week, an analyst priced Blue Apron at $2. Today (July 17) the stock fell 10.6%. Since its June 29 IPO, the company has lost 34% of its value.

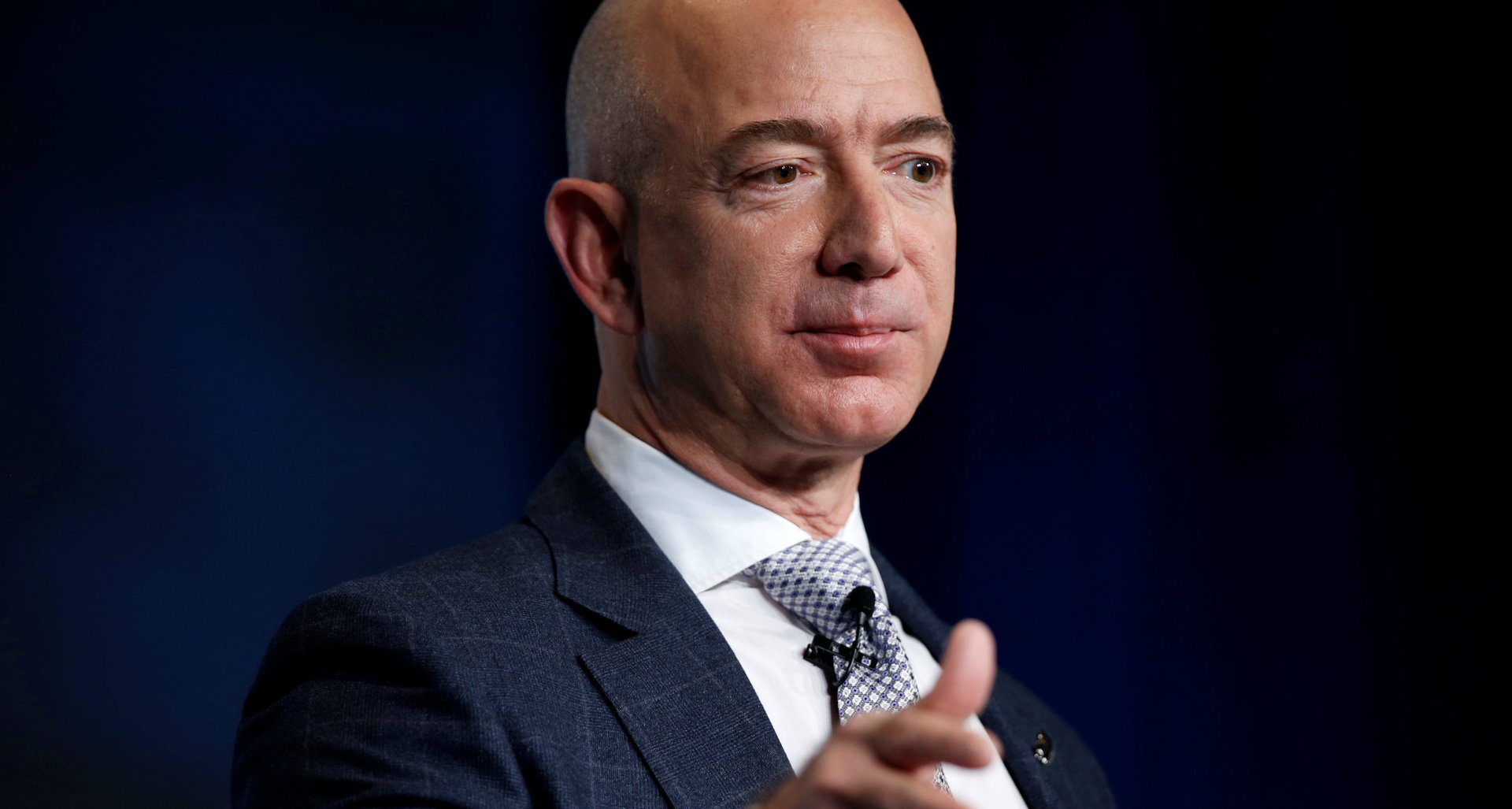

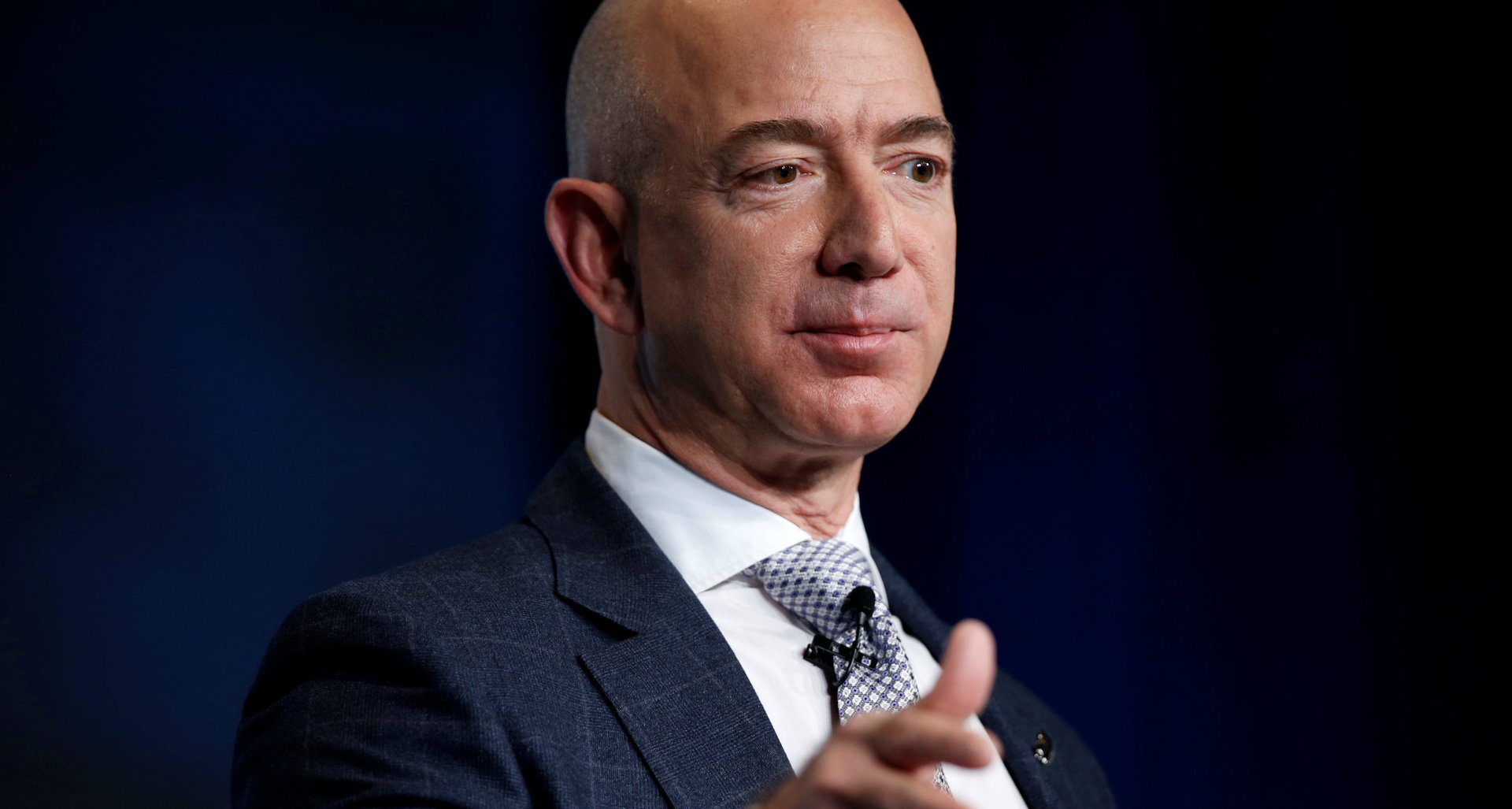

Investors are scared, and they should be. Jeff Bezos set his sights on grocery long before Amazon announced its deal with Whole Foods, but it’s only in the last month that the company has begun an all-out assault on competitors in the grocery and food delivery sector. It’s not just Blue Apron that should be alarmed. It’s HelloFresh and Sun Basket and Postmates and DoorDash and, yes, Grubhub. It’s also mainstream grocers across America, who were already on notice. Many have been partnering with Instacart and a handful of other grocery-delivery startups to defend against Amazon’s slow and inevitable advance into their business.

Bezos hasn’t told grocery stores and food delivery companies to watch out—he doesn’t have to. Despite what companies like Blue Apron and Postmates may have told their investors to raise venture capital, delivering groceries and food is less a technological challenge than a logistical one. And there is no more formidable logistics opponent in the US than Amazon.

Many companies, Amazon included, have tried to crack grocery delivery and failed. Groceries—particularly fresh ones—are a tough thing to sell online. Amazon used to waste nearly a third of the bananas it purchased because it only sold them on AmazonFresh in bunches of five, but bananas sometimes choose to grow in bunches of a different number. Fresh food also goes bad quickly and grocery stores are hardly known for making a lot of money. Still, groceries are also one of the few things that most people purchase routinely, which is why so many stores—both online and offline—believe a good grocery offering is key to gaining new customers and keeping existing ones satisfied.

What’s scary to think about is that Amazon’s consumer loyalty is already unparalleled. As of late June, there were 85 million Amazon Prime users in the US, or an estimated two-thirds of US households, according to Consumer Intelligence Research Partners (CIRP), a leading research firm on all things Amazon. Those Prime customers spent on average $1,300 a year and made up 63% of all Amazon users in the US.

Amazon Prime costs $99 a year or $10.99 a month. It doesn’t currently include grocery delivery through Fresh, which costs an additional $14.99 a month. But one day it might. It’s easy to imagine a world in which Prime membership gets a little bit more expensive and entitles you to free online grocery ordering and pickups at Whole Foods—if not free unlimited grocery delivery from Whole Foods and Fresh. The same goes for food delivery, and for meal-kits. Amazon has registered its interest in the meal-kit business and is actively building out one-hour delivery from restaurants for Prime members in major US cities.

Put another way: Amazon is a competitor to Blue Apron, but Blue Apron is barely a competitor to Amazon. Its meal-kit business is just another thing that Amazon can and likely will pursue, maybe one day to become another line on the list of benefits included with a Prime subscription. No wonder Blue Apron’s investors are jumping ship.