Chinese military ships are popping up everywhere—and highlighting an embarrassing double standard

China clearly knows its rights under the law of the sea. But whether it can accept others having those same rights remains to be seen.

China clearly knows its rights under the law of the sea. But whether it can accept others having those same rights remains to be seen.

In recent weeks, Chinese warships, coastguard vessels, and spy ships have popped up near Alaska, Japan, and Australia. While they weren’t in violation of international law, their presence serves as a reminder that China is becoming a major maritime power and suggests it will take fuller advantage of what’s permitted under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos).

That, in turn, is highlighting China’s use of double standards.

“At the moment what we see is a double standard where China picks the areas of the Law of the Sea that it likes and refuses to implement those that it doesn’t,” the Lowy Institute’s Euan Graham told Australia’s ABC News. While recent incidents show other countries are tolerating China’s presence near their coasts—even when its presence is described as “unfriendly”—there are many examples showing Beijing hasn’t been so generous, instead accusing other nations of illegally entering its waters.

A spy ship off the coast of Australia

When Graham commented on China picking and choosing what it likes from Unclos, he was referring to a Chinese spy ship recently operating off the Queensland coast just as US and Australian forces were conducting joint military exercises nearby, as Australia’s defense ministry observed on July 22. Its presence there might have been a first. ”I’m personally not aware of any publicized appearance of an AGI [auxiliary general intelligence vessel] off the Australian coast before,” Graham added.

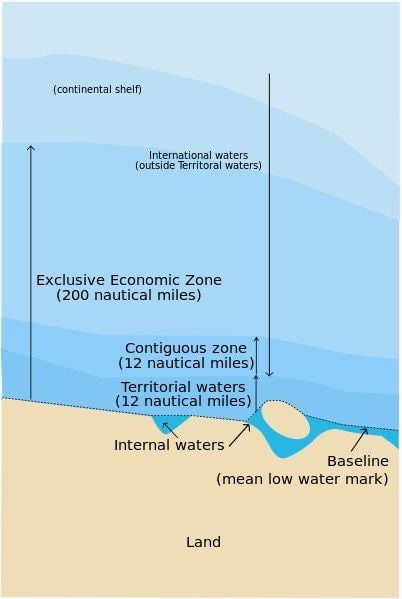

The spy ship didn’t break any rules. It operated within Australia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), as allowed under the rules of Unclos. Extending 200 nautical miles (370 km or 230 miles) from the coast, the zone can be regarded as international waters, except that any resources within it—such as fish or natural gas deposits—belong to the coastal nation. Australian military officials described the ship’s presence during the drills as “unfriendly,” but added that they respect the right of other nations to exercise freedom of navigation in such waters in accordance with international law.

China, however, is among a small group of nations that interprets Unclos rules to mean it can regulate foreign military vessels within its EEZ. US and Indian navy vessels operating in China’s EEZ have on numerous occasions (pdf, p. 10-11) been threatened and harassed.

Another spy ship near Alaska

This month a Chinese spy ship arrived off the coast of Alaska shortly before a test of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (Thaad) system against an intermediate-range ballistic missile. Because the ship was clearly within the US’s EEZ, not its territorial waters, US forces left it alone to conduct its reconnaissance, recognizing that it had a right to operate there. The US does the same thing, after all, in the EEZs of other nation. (Though the US never ratified Unclos, it does abide by the norms set forth in it.)

Coastguard ships in Japanese territorial waters

This past weekend, meanwhile, two Chinese coastguard ships briefly entered Japanese territorial waters near two islands off Kyushu. Japan’s coastguard said it was the first time Chinese government vessels had entered those waters. Again, the ships did nothing wrong under Unclos. In territorial waters, which extend 12 nautical miles from the coast, the coastal nation has stronger rights to enforce its own rules than in an EEZ. But even there, foreign vessels have the right to conduct “innocent passage,” or to pass through without stopping or doing something of a military nature.

China, however, has raised a fuss when US ships have conducted the same kind of innocent passage next to its artificial islands in the South China Sea. In 2015, for instance, China complained about the USS Lassen “illegally” entering waters near Subi Reef in the Spratly archipelago, and even sent two destroyers to warn the vessel off. That was despite doubts as to whether the artificial island that China had built atop Subi generated any territorial sea at all. A ruling by an international tribunal a year ago determined that Subi, in fact, did not.

Meanwhile, China is conducting drills with Russian ships in the Baltic Sea—another first—and it recently shipped troops to man its first overseas base on the coast of Djibouti, a tiny country in East Africa near Yemen. As China operates ever further field, it will increasingly need to operate in the EEZs of other nations. Whether that convinces it to drop the double standard remains to be seen.