Computer scientists reveal the hidden architecture of tax havens—and how to beat them

We know there are tax havens. We just can’t agree on where they are.

We know there are tax havens. We just can’t agree on where they are.

Although many countries recognize that major corporations divert tax revenue—there’s a reason, after all, why US multinationals hold more than $2 trillion overseas—collective action is tough.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and the International Monetary Fund have both worked to identify offenders, but as multi-national organizations, they’re don’t tend to call out member states for breaking the rules. As far as the OECD is concerned, the only tax jurisdiction not abiding by its rules is Trinidad and Tobago.

Some look to economic statistics to make the tax haven case. It’s easy to spot US corporations whose earnings in a country outstrip that nation’s GDP. But overall foreign direct investment measures can be unreliable, and don’t reveal the path money took to reach its final destination, so enforcement remains challenging.

That’s where new research from a group of European computer scientists comes in. Javier Garcia-Bernardo, Jan Fichtner, Frank Takes & Eelke Heemskerk collaborated on a new technique to find tax havens.

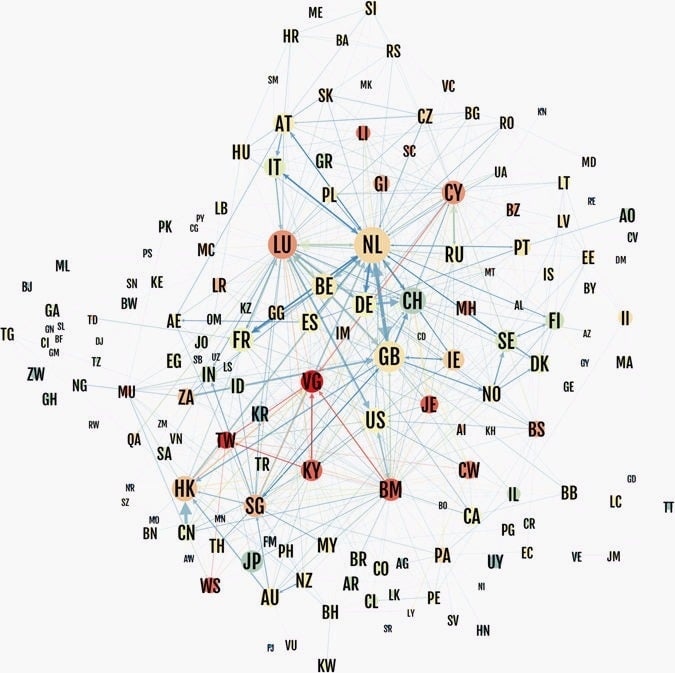

Using a global dataset that tracks the relationships between more than 98 million companies, the researchers used algorithms to build a network that identified the relationships between corporate subsidiaries, tracing the flow of tax-free money from country to country through these corporate chains.

This technique allowed them to make a key distinction, between offshore financial centers that act as conduits from major markets, and their final destinations, offshore financial centers that act as sinks for capital.

The results were illuminating. Many of the “sink” jurisdictions won’t surprise you, with the British Virgin Islands, Jersey, Bermuda, and the Cayman Islands, all notorious low-tax jurisdictions, earning spots in the top five. But there is a surprise: Taiwan is a top capital sink. It’s not normally thought of that way, but it makes sense when you look at the role it plays in China’s economy.

“The prominence of Taiwan is driven by Taiwanese technological companies, which often own Chinese firms through Hong Kong (33%) and Caribbean Islands (20%), or own Hong Kong firms through Caribbean Islands (12%),” the authors wrote. “Due to pressure by China, Taiwan does not participate in FDI statistics collected by the IMF and therefore was not detected by studies relying on aggregated international FDI data.”

What’s really interesting in this network analysis, however, are the conduit jurisdictions. For example, despite the fame of the “Panama papers,” Panama’s high tax rates actually make it a poor corporate tax haven and it doesn’t make the sink list. Instead, its corporate secrecy laws make it a good conduit for funds to flow to their final destinations.

These conduits represent the heart of the global offshore system. And there are five primary offenders: The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Singapore, and Ireland. each of which specializes in navigating cash in and out of key markets for specific industries.

The researchers say that spotting these conduit states using a quantitative method can give ammunition to efforts to shut down the flow of untaxed money.

“While efforts usually focus on small exotic islands, we showed that the main sinks of corporate ownership chains are highly developed countries which have signed numerous tax treaty agreements,” they write. “Moreover, we showed that only a small number of conduits canalize the majority of investments to typical sink-[offshore financial centers] such as Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, or Jersey (which, in fact, are all under the sovereignty of the United Kingdom).”

Governments haven’t done a very good job so far of preventing multinational corporations from exploiting the fractured mess of tax jurisdictions in the world market. But with investigations they like this, they will have little ground to claim ignorance about how the system works.