Financial robo-advisors are finding that a little human touch goes a long way

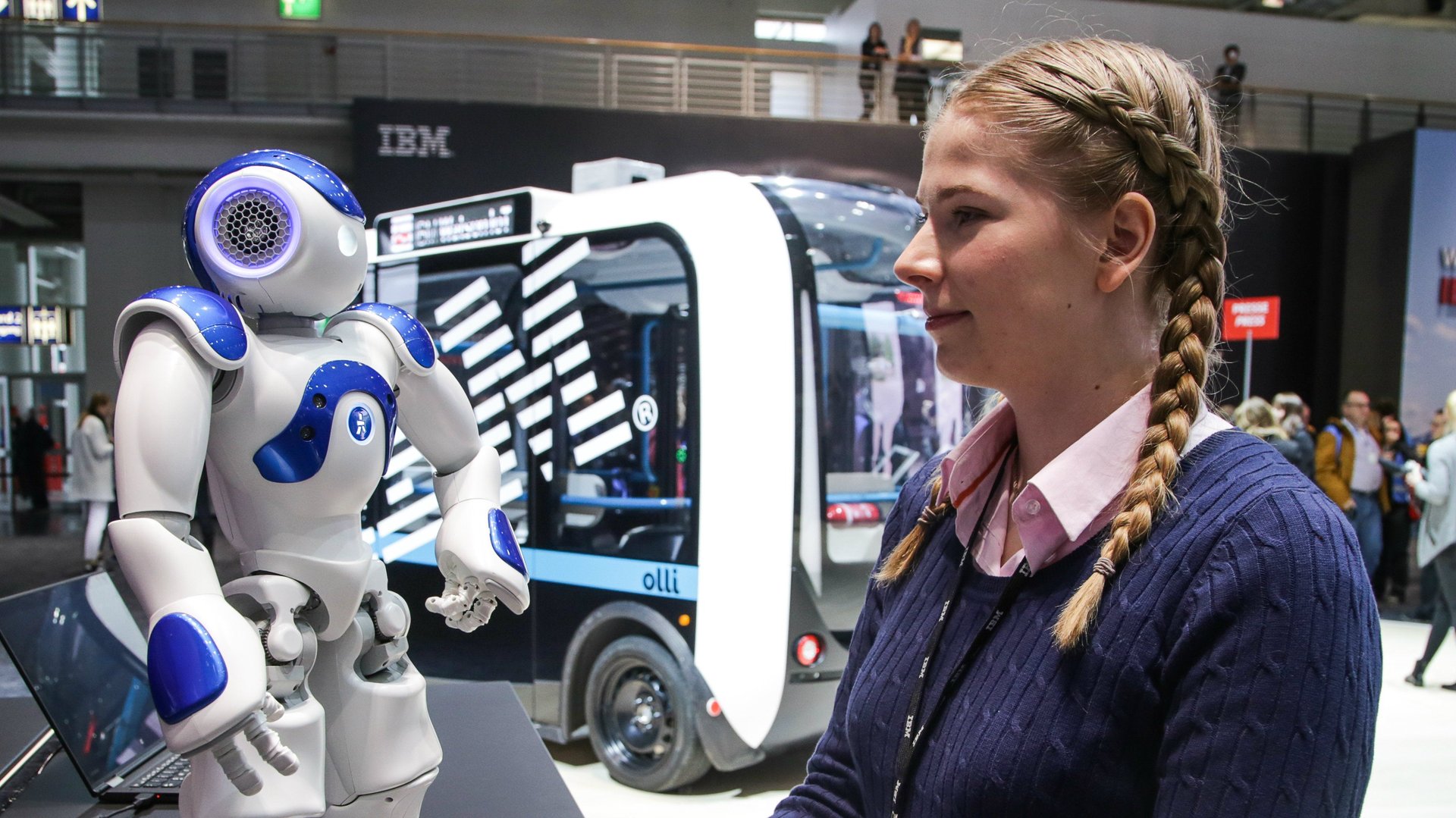

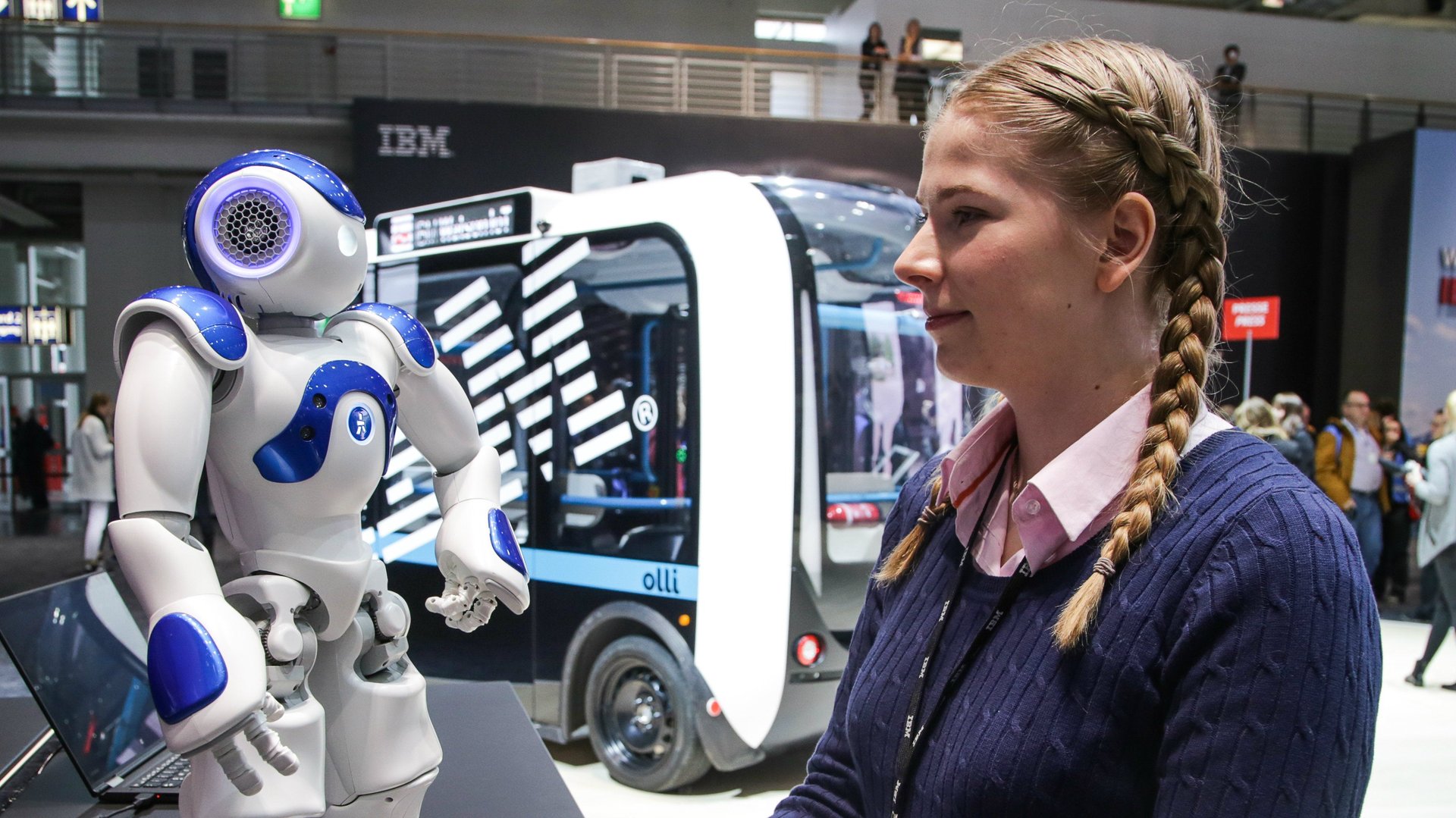

A great dilemma of modern life is how much we allow ourselves to rely on machines. It’s a heated debate in the investing world, where increasingly sophisticated algorithms are available to offer financial guidance. Companies are trying to figure out the right mix of human and algorithmic interaction that makes clients most comfortable.

A great dilemma of modern life is how much we allow ourselves to rely on machines. It’s a heated debate in the investing world, where increasingly sophisticated algorithms are available to offer financial guidance. Companies are trying to figure out the right mix of human and algorithmic interaction that makes clients most comfortable.

That’s the thinking at Betterment, a pioneering “robo-advisor” that’s injecting more of a human touch into its app. It still offers automated portfolio management, but now anyone who has signed up for an account can send text messages to human advisors and get a response in about 24 hours. Its staff can give suggestions on things like how to save to buy a house or which type of account to set up.

Betterment was originally an all-digital service, but added a human advisor option to premium plans earlier this year. Fund manager Vanguard also has a hybrid offering, with by far the most assets under management. The majority of that money has come from existing customers who swapped into the partly robo-run service. (Size matters because fund managers and wealth advisors are often paid a percentage of the assets they oversee.)

Wealthfront, by contrast, is 100% robot and sticking with it. The company is betting that millennials are more comfortable figuring things out on their own via an app than chatting with an advisor.

Automated wealth management has great promise: it could provide investing advice and share best practices to people who didn’t have access to such things before. Money that’s sitting idly in savings or checking accounts could flow into the financial system, giving entrepreneurs the capital they need to grow their businesses and create jobs.

UBS, for example, has a lot of wealthy clients, but its robo-advisory offering can reach people who haven’t had access to the Swiss bank before; its SmartWealth service has a $15,000 minimum investment, a lower bar than many of its other offerings. It says customers of the service still get the benefit of the bank’s 1,000-strong staff around the world.

A downside is that robo-advisory services ares fairly new, and nobody knows how they will hold up during a major market panic or severe economic downturn. Some worry that machines could move in lockstep, exacerbating price swings when times are tough.

For now, the amount of money managed via robo-advisory services is still small compared with the trillions of dollars overseen by the sector overall. But the segment is growing quickly, and the industry is taking it seriously. According to Shane Williams, co-head of UBS SmartWealth, in the coming years, as the key players figure out the best mix of automated and human-led strategies, some start-ups will fail, others will be acquired, and only a few will be successful in the long-term.