“I was urged to stop paying my bills to invest in more inventory. I was urged to get rid of television. I was urged to pawn my vehicle. I just had to get on anxiety meds over all of it because I’ve started having panic attacks.”

In June 2016, Sophie (name changed) quit her job in the suburbs of Fort Worth, Texas to sell for LuLaRoe, a rapidly growing clothing company that offers self-employment opportunities to American women in the form of hawking hyper-hued apparel. LuLaRoe’s consultants told her—and tens of thousands of other mostly rural and suburban women over the past five years—that she could provide for her family, join a sisterhood of supportive women, and find meaning in her life again through the conduit of colorful, stretchy fashion—all for a reasonable upfront investment of around $5,000.

As economic opportunity has become more concentrated in urban areas in the US, rural communities have fallen behind. Residents of towns like Casper (Wyoming), Spring Creek (Nevada), and DeRidder (Louisiana) all missed out on economic recovery following the 2007 global financial crisis. Bootstrapping, hard-working families in these regions are urgently searching for a way to regain their economic liberty, along with their dignity.

Fed the fantasy of achieving the all-elusive American dream, many of them are being wooed by multilevel-marketing companies. Known as MLMs (or “direct-sales”), the current US administration is stocked with their cheerleaders: Betsy DeVos, the secretary of education, is married to a cofounder of Amway; Ben Carson is a spokesperson for a vitamin MLM called Mannatech; and president Donald Trump used to have an MLM, Trump Network, and was a spokesperson for another.

Joining a MLM is appealing to women who find hope in their promises of a better life: freedom, economic independence, and an endless supply of cheery trinkets. Despite professing quick-income prospects though, it’s difficult for MLM consultants to earn more than pocket change. When glitzy recruitment videos yield to the reality of suburban cul-de-sacs, people selling for MLMs can be plunged into debt and psychological crisis.

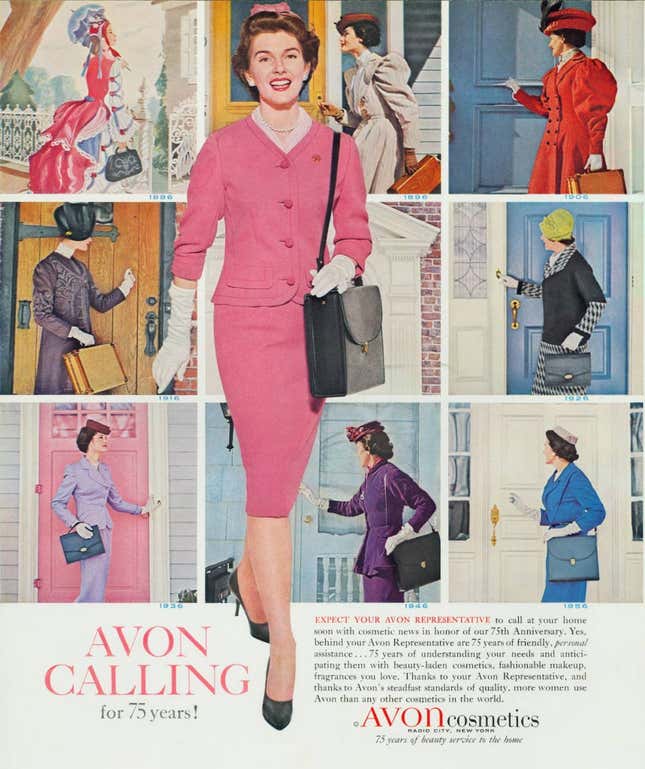

MLMs aren’t a new business model—they’ve just done a little rebranding. A lot of the old guard such as Avon and Mary Kay are still around, but nowadays, some of the most popular MLMs include Herbalife and Plexus (nutrition and weight loss), Young Living and DoTerra (essential oils), Pampered Chef (kitchen tools), Rodan + Fields (skincare), and Jamberry (nail stickers).

Of these second-wave MLMs masquerading as women’s empowerment, LuLaRoe is queen. More than 80,000 women have paid around $5,000 for several boxes of low-cost clothing and worked as much as 80-hour weeks to outfit hundreds of thousands of suburban women in multicolored polyester. But according to a report that studied the business models of 350 MLMs, published on the Federal Trade Commission’s website, 99% of people who join multilevel-marketing companies lose money. Depending on how you look at it, it’s either a brilliant business model or a predatory practice—or a little bit of both.

How do MLMs work?

MLMs sell themselves using self-empowerment language and sparkly beauty products. They’re #girlboss mythology repacked for Christians and Mormons; entrepreneurialism for women brought up believing men should be the breadwinners; and a peppy dream for millennials who were told they could do anything.

MLMs only sell through a network of consultants, not in online stores or in brick-and-mortar shops. Sellers buy inventory from a parent company and sell it to their friends and family, keeping the profit for themselves like a franchise would. But the real potential to earn money generally isn’t in peddling wares: It’s in building up a team of sellers below you and getting a cut of their commissions. Once a seller has recruited new consultants, she has to push them to buy more inventory each month or to hit consumer-sales targets in order to earn her bonus check and keep the money flowing upstream. This means the further down the recruitment ladder you are, the less opportunity there is to make real money.

The difference between a MLM and a pyramid scheme can be blurry, both legally and practically. It’s never been legally defined in the US by a statute, but the FTC defines it as whether a consultant can make an income by selling to the public alone without having to recruit consultants underneath them. “Not all multilevel marketing plans are legitimate,” the FTC states in its literature on MLMs. “If the money you make is based on your sales to the public, it may be a legitimate multilevel marketing plan. If the money you make is based on the number of people you recruit and your sales to them, it’s probably not. It could be a pyramid scheme. Pyramid schemes are illegal, and the vast majority of participants lose money.”

“The majority of [retailers] earn income from only selling LuLaRoe clothing and not through participation in the Leadership Bonus Plan,” says a LuLaRoe spokesperson of their recruitment-based bonus structure. “LuLaRoe’s success is based on [retailers] selling the comfortable and stylish clothing to consumers, not ordering more inventory.” LuLaRoe says that in 2016, 72.63% of their consultants earned their income through selling clothing alone.

LuLaRoe also says it invests “considerable time, resources, and talent” to support its “independent retailers,” as it calls its consultants. If they experience financial or psychological hardship through operating their businesses, it says it’s not the company’s fault. “Retail is not for everyone,” says a LuLaRoe spokesperson. “Retailers own their own business and make their own decisions…The success of any business depends on its leader’s own respective and independent business goals, and the strategies they employ to achieve those goals.”

However, MLMs are nearly never the get-rich-quick plots their advocates promise. “The number of people who actually succeed at that is very small,” says Douglas M. Brooks, an attorney who represents victims of pyramid schemes. “And some do—people will get up on stage and wave checks around, but they represent a fraction of 1%.”

One such success story is Nicole Haas of Williamsburg, Virginia. A bubbly blonde and former personal trainer, she put $12,000 on a low-interest credit card to start her LuLaRoe business in January 2017. Through working 25 to 30 hours a week, she paid off her credit card in May and now puts $3,000 a month in her family’s account, less taxes. “It’s changed my life,” she says. “It’s changed who I am as a person.”

According to the Direct Selling Organization, she’s one of more than 20 million Americans who participated in direct sales in 2016. It’s a booming business, racking up an estimated $35 billion that year, a 30% increase from 2010. You might have been roped in yourself and not even realized it: If you’ve ever received a perky Facebook message from an old friend inviting you to a party at her house, had a cousin say she has a business opportunity that could help you take control of your life, or been handed a colorful business card outside of Target by a woman spilling with compliments, you might have been charmed by an MLM seller.

MLMs disproportionately flourish in suburban and rural America: According to LuLaRoe’s retailer map, it only has 10 consultants in all of Manhattan, which has a population of 1.64 million. By comparison, Pueblo (Colorado) has the same amount for its population of 110,000, St. George (Utah) has 12 sellers to its 82,000 residents, and Idaho Falls (Idaho) and Casper (Wyoming) both have nine sellers servicing each’s 60,000 citizens. In 2016, the US Census Bureau stated that the median rural household income is 4% lower than it is for urban families, and income inequality is also higher. Job growth in metropolitan areas has far outpaced that in rural areas since 2008, and the job market in these regions has shrunk 4.26% in the same time.

The US government tried to help people understand the risks before joining these kinds of companies, but MLMs had their way. In 2012, federal legislation passed requiring all franchise companies to provide a disclosure document with information on weighing the benefits and risks of signing up. However, MLMs poured money into lobbying and flooded the FTC with more than 17,000 comments from consultants saying the disclosure would be a burden, and asked to be excluded. The FTC complied, and now MLMs aren’t required to disclose information on risks to interested consultants.

As a result, many women sign up unaware of just how hard the system makes it to earn a living selling for a MLM. “I’m trying to make it work the best I can without letting my family know I pretty much signed up for a pyramid scheme,” says Kayla, a consultant in her twenties who lives in rural Wisconsin.

Quartz agreed to Kayla’s request not to use her last name to protect her anonymity, and gave pseudonyms to others. Several of LuLaRoe’s sellers declined to go on the record with Quartz using their full names, citing concerns about possible reprisals from the company due to a non-disparagement clause in their contracts, and concerns about being harassed by other sellers. This fear only perpetuates the cycle as it pulls more women into its spiral.

Introducing LuLaRoe

Ask any woman living in the suburbs of America’s Bible Belt, and chances are she will be able to tell you all about LuLaRoe.

Founded in 2012 by a Mormon mother, Deanne Stidham, LuLaRoe is named after her three grandchildren, Lucy, Lola, and Munroe. As the company lore goes, she designed clothing for her daughter and had so much success selling copies to the parents of her daughter’s friends that she hired consultants to sell for her. In just four years, her company’s range of leggings, dresses, shirts, and other wares generated $1 billion in sales, making it one of the largest MLMs in the US; between October 2016 and June 2017, it claims it sold nearly 40 million pairs of leggings. Mary Kay, one of the oldest and most successful MLMs, had $4 billion in sales in 2015.

During the Mary Kay heyday in post-war America, consultants would invite their friends to in-home parties (think Tupperware) or go door-knocking to sell their products in their neighborhood (think Girl Scouts). However, in the digital age, the game has changed. Consultants who had previously run out of doors to knock on or neighbors to invite over had to put their goods in a car and drive to the next town for fresh clientele. Now they just form a group on Facebook, fire up a Live video stream, and sell to eager customers across the country, like their own miniature Home Shopping Network.

Using this model, LuLaRoe sellers busted out of the traditional confines of heritage, Avon-style MLMs. One of the reasons Avon had so much success in the 1960s was that it was the easiest way for suburban Americans who were an hour away from the closest department store to sample and buy makeup. Convenience won out. Now Facebook can provide their contemporaries with that same easy purchase availability from the comfort of their couches.

Sarah Stern, a stay-at-home mom in southern Florida, signed up with LuLaRoe in March 2016 after receiving a glowing review from a friend. “She told me that they have a cult following, the clothes sell themselves, and it’s under 10,000 people now, so you want to get in while it’s on the ground floor,” she says. Stern joined her friend’s LuLaRoe Facebook page and saw women fighting in the comments to buy beautiful leggings and dresses. She showed her husband, a VP of sales for a consumer-products company, the profit margins, and he told her to go for it.

“I did pretty well for myself,” says Stern, who split sales with her business partner. The work was part-time, and she pulled in anywhere from $5,000 to $10,000 a month in revenue. Every month, the head of her consultant group would post a leaderboard for the top inventory buyers and sellers, some of whom were bringing in up to $60,000 a month. Stern noticed that the amount of inventory bought correlated with higher income, so after attending one of LuLaRoe’s touring conferences, she was inspired to bulk up her inventory. She and her business partner went on a buying spree, posting pictures of all the unopened boxes on her Facebook page, which began to swell with excited customers.

Shortly after, Stern began to pull in anywhere from $18,000 to $24,000 a month in sales. She was working 80-hour weeks with seven women selling underneath her. “The moment I woke up, I was taking pictures and answering questions,” she says. “My husband had to do the food shopping. My daughter has dance one day a week. While she was dancing, all the other moms would talk, but my face was always in my phone. I was uploading albums, or I was part of a multi-consultant sale.”

Stern jumped in during the heyday phase of a MLM when the people at the top grew rich, and quick. By the start of 2017, nine months after Stern joined, LuLaRoe was pushing 80,000 independent retailers. According to interviews with several consultants, this is also the time when sales suddenly became tougher: The hundreds of thousands of ravenous customers who once clamored to buy leggings from 10,000 consultants flipped in less than a year to eight times that amount selling to just a fraction of the clients. The scales began to tip.

According to internal consultant calls, LuLaRoe is still onboarding more than 150 retailers a day. (LuLaRoe declined to confirm how many people are joining daily.) In this spandex rush, so many women were signing up to sell LuLaRoe that the onboarding queue stretched for weeks. Former customers were often convinced to become sellers so they could get their own wares wholesale, plus hopefully make some profit on the side. “Every time I got a really good customer, they would sign up under someone else,” Sophie says.

“As of the end of first quarter 2017, approximately 90% of all retailers who started an independent fashion retailer business since the time LuLaRoe was founded still maintain their businesses today,” says a LuLaRoe spokesperson. “We are very proud of this figure.” In part due to this high retention rate, the market is becoming saturated, both online and off. Multiple retailers now often live within a few blocks of each other—and how many pairs of leggings does one neighbor really need? “They’ve flooded the market with so many consultants, nobody is making money, and everyone is so stressed out,” Sophie says. “Now it’s like, ‘Oh, there’s another consultant down the street.'”

“One of the unique facets of this business is that the victims are also perpetrators,” Brooks says, speaking generally of MLMs. “You’re trained to recruit your friends and family and neighbors.” He points out that when you onboard someone underneath you, especially if they live in your town or are in your friendship group, you are essentially creating a competitor. It’s as if you open a Subway sandwich shop and then encourage your neighbor to open a Subway right next door—and everyone is already sick of sandwiches.

Selling the dream

LuLaRoe’s messaging is filled with positive language: “I believe in you” is the company’s unofficial tag line, and body-positive imagery floods its website to showcase its large selection of flattering plus-size outfits. “It’s hard to find plus-size clothing that actually looks good—that makes you feel like you look good,” Sophie says. “That’s why there’s such a customer base for LuLaRoe.”

There’s another positive that consultants always emphasize: friendship. MLMs often provide a sense of belonging for their consultants; a crucial lifeline for moms sitting at home with only the kids to talk to. “I had come out of a rough situation, a custody battle,” Sophie says. “I was lost. I had no friends, I had no social life. And then instantly I had this giant family of women who I didn’t even know. ‘We love you. What do you need? Let me help you. You’re having trouble with sales? Let me share my customers with you. You can’t make an order this month? Let’s trade shirts so we have new inventory.’ It was a true, true sisterhood.”

LuLaRoe gives these women a way to have it all: a career, new friends, body confidence, extra money, all with enough time left over to be an excellent mother and wife. “Want to earn full-time income for part-time work? Ask me how!” reads a sign that was sent out to new consultants last year. Stidham often promotes the idea of her company being a perfect part-time job for mothers by talking about being a single mother of seven hustling out of her home—even though she was already remarried and her kids grown before LuLaRoe was founded.

Ashley (name changed), a mom and wife who lives in the suburbs of Indianapolis, signed up to sell LuLaRoe in August 2016 after her husband lost his job and was only able to make half his salary at the next one he found. “Simply put, I signed up to make money,” she says. Ashley opened three credit cards to cover the initial set-up cost and generated $3,500 a month in revenue for the first two months. But on the advice of other retailers, she plowed it all back into buying more inventory instead of keeping any of it for herself, her family, or their mounting bills. “Often increased inventory can assist in increasing retail sales to consumers,” says Justin Lyon, LuLaRoe’s chief marketing officer.

Sales started to decline in the third month. Her consultant group told her it was because she didn’t have enough inventory, so Ashley followed their advice and bought even more. As sales continued to decline, she used her income-tax rebate to buy more, but it didn’t keep her sales from bottoming out at $500 a month. “There was a point in time where I had $8,000 worth of inventory sitting in my home while I was running up to food banks to feed my family,” she says. “I really feel like I failed my family.”

“Retailers should absolutely never put their personal financial situation at unreasonable risk to establish or operate their retailer business. Period,” Lyon says. “If any retailer is encouraged to do that, we do not support it.”

Regardless of LuLaRoe’s official policy, the selling community is rife with consultants strong-arming risky decisions with smiling faces. Emails outlining new policies are sent out to independent retailers directly, who then discuss the company’s communications between themselves. Directives for how to interpret rules are often filtered through Facebook groups by team leaders eager for bonus checks, leaving the door to miscommunication—and manipulation—wide open.

“These girls would listen to [their] leader as the Bible,” Stern says.

Getting started

Kayla lives in a small town in Wisconsin. She’s single, 27, childless, and in grad school. In late 2015 she was working as an administrative assistant at an office earning $32,000 a year when a sorority sister from college invited her to a LuLaRoe in-home party. She was initially resistant to the very idea of leggings as pants, but she walked away with several dresses for $65 each. “I realized if they’re making the money that they say they’re making all over their Facebook pages and how it’s life changing, why can’t it change my life?” she says.

Kayla assumed she could just buy a couple of hundred dollars’ worth of leggings to get started, but she found out that she was required to buy a startup inventory package, which costs between $4,900 and $6,000. “Initial inventory packages are designed to provide sufficient inventory to help retailers succeed,” says a LuLaRoe spokesperson. “If a retailer can’t afford it, a retailer should not buy it.”

At this point, even if she had quit the next day without selling a thing, LuLaRoe would have made its profit. Kayla acquiesced on Jan. 1st, 2016—and was then immediately encouraged by her upline to buy an additional $1,000 in Valentine’s Day-themed clothing. (Brooks says this tactic is called “channel stuffing” or “inventory loading.”)

She was told by one of the consultants in her Facebook group to take out a low-interest credit card to pay for the initial buy, and that she would pay it back within eight weeks at the most. If a consultant’s credit isn’t good enough for a card, some communities of sellers encourage would-be consultants to raise money; there are currently over 400 GoFundMe campaigns to start a LuLaRoe business.

How long would it take a seller to earn back their initial $5,000? Let’s say she sells 30 leggings in an online party. They cost $10.50 each wholesale, and the manufacturer’s advertised price is $25, so she would make a $435 profit. After that, consultants often tell other sellers to replace their inventory and build up more in order to be successful. “The question of inventory levels is determined by each retailer in the conduct of the retailer’s own independent business,” says a LuLaRoe spokesperson. “If the retailer believes greater inventory would help, they are encouraged to order.”

The minimum order is 30 pieces at a time, and LuLaRoe requires sellers to buy a minimum of 33 pieces a month ($346 in wholesale leggings, for example) to maintain active status. This means that if a retailer sold 30 pairs of leggings a week, it would take them just under three months to make back their initial $5,000. As they also need to use their revenue to restock an additional 33 pieces a month ($1,038 worth of leggings over 11.5 weeks), it would therefore take another month or so of selling 30 pairs of leggings a week to start turning a small profit. (There is a more detailed mathematical breakdown of different business models here.) “Just like anyone starting a new business, there is risk involved and not everyone is guaranteed success,” LuLaRoe CMO Lyon says.

After earning $3,000 to $5,000 a month for a few consecutive months, Kayla quit her job in late 2016 to sell LuLaRoe full time. “The next month my profits took a dip. And the next month my profits took a dip,” she says. “I’ve not been able to recoup anything since I quit my job.” After trying to sell off as much inventory as she could, she resigned from the company last month and is awaiting her refund check—which, at the time of writing, still hasn’t arrived.

But for most MLMs, the real money isn’t in selling wares: It’s in signing up consultants. Up until July 2017, LuLaRoe’s sellers who signed up new retailers got a 3-5% commission on the inventory their downline bought. But they only garnered that commission if they and everyone underneath them each bought 175 pieces a month, a rule that incentivized inventory buying.

Some variation on this structure is common at most MLMs. Financial analysis on Pink Truth, a website that analyzes Mary Kay and other MLMs’ business practices, estimates that as a LuLaRoe seller advanced up the ranks, had 10 people below her, and garnered 3% of her recruits’ inventory-buy value, she could make a bonus of $1,500 a month—but only if her downline spent about a combined $35,000 on merchandise. That’s why struggling sellers used to be told to buy more inventory: Not only did their higher-ups get a cut of each bulk buy, but if their downline didn’t hit the minimum purchase mark, no one got a bonus. “The entire year that I did LuLaRoe, I was pushed to continue buying and buying more and more and more, no matter how the sales declined, and that buying more and more was the only solution to get more sales,” Sophie says.

On July 1, LuLaRoe instituted a much fairer Leadership Bonus Plan (pdf) that awards compensation based on sales to consumers rather than wholesale purchases. But there are still thickets of obscure rules: Leggings only count as half a piece; your bonus is based on your downline’s wholesale value of sales, not their retail value; and your team’s per-piece average needs to be at least $30, meaning that if you want to get your bonus, you can never sell your wares for discounted prices.

With the company’s rules shifting and no small-business training offered to consultants, it’s easy to let enthusiasm blindside reality—and if you’re drowning, you’re fighting against a riptide of consultants to save yourself.

You vs. the community

The upper echelons of LuLaRoe’s consultant community have a reputation for being vicious to their downline. “It’s like the policy police,” Ashley says. “‘We’re going to find you, stalk you, tell on you. How dare you guys say a single word bad. We’re going to shame you.'”

Whether they realize it or not, consultant leaders often use time-honored cult tactics of denial and blame to keep women within their sorority. A famous series of experiments from the 1950s conducted by Soloman Asch in England showed that three out of four people will deny evidence right in front of them if the majority says it’s not true. In the study, individuals were placed in groups where they were constantly contradicted by other members. When this happened over a length of time, they would start to agree with the majority—even though it was clear that the opposite was true. In MLMs, “you’re trained to avoid people who question whether this is a viable business or not,” Brooks says. “Which is exactly the same technique that cults use—they try to isolate you from people who question your belief system. I’ve been contacted by a number of people who deal with cult survivors, and some of their clients are former MLM people.”

Even when consultants wake up to the fact they’ve been hoodwinked, many don’t warn their friends to stay away. That’s because if you speak out against any of LuLaRoe’s rules or mishaps, the community could publicly shame and harass you for being negative. “I can’t believe you call yourself a Christian,” one retailer wrote to someone trying to sound the alarm. “Where is the Jesus in you? I have to block you due to your constant-gross-delusional-uneducated opinions of LLR.” If you reveal you are struggling to make sales, you might be told to stop playing the victim, that you’re not putting in enough effort, to be more enthusiastic, and, of course, to buy more inventory.

“Success as a retailer results only from successful sales efforts, which require hard work, dedication, diligence, leadership and perseverance,” says a LuLaRoe spokesperson. “Success will depend upon how effectively these qualities are exercised. As with any business, results will vary. In addition to the factors above, retailer success is influenced by the individual capacity, business experience, expertise, and motivation of the retailer.”

In other words, it’s not the system that’s broken—you’re just not trying hard enough.

To try and understand what LuLaRoe success looks like, I studied Nicole’s Facebook Live stream. What was she doing so right? Nicole and another consultant pulled out 71 pairs of leggings in an hour. They deemed almost every one “pretty,” “beautiful,” or “cute.” The most egregiously ugly leggings—like one pair covered in paintball splats with flowers overlaid on top—were “fun” and “different.” In an MLM, saleswomanship is key, no matter what the wares you’re selling look like.

They ended up selling 20 of them over the next 24 hours.

Leggings anonymous

Many LuLaRoe Facebook groups have the word “addiction” or “addicts” in their titles: Christine’s LuLaRoe Addicts Anonymous, LuLaRoe Addicts, LuLaRoe Addiction VIP Boutique. It’s supposed to be a joke, but it’s truer than many women realize.

Mary (last name withheld) is a wife and mother who holds a master’s degree in nursing and works from home in Arizona. She bought her first pair of LuLaRoe leggings in 2015 and loved them. But what started as a fun social activity turned into a compulsion, and she found it taking over her life. “I spent more hours than I want to admit ‘hunting’ that pair,” she says. “I spent more than $3,000 in a month. I would lie to my husband about feeling ill so he would take the kids to their afterschool activities so I could be at home to watch pop ups. I would also drive as far away as an hour to attend LLR events.”

LuLaRoe merchandise boxes are like Lycra slot machines. In the onboarding package, new recruits don’t get to choose the size or style of their items. For example, Sophie knew plus sizes would sell best for her, but her initial package contained five XXS dresses and several long-sleeved shirts that were a tough sell for a Texas retailer in June.

After that package, consultants can start choosing styles and sizes for their next orders, but they never get to choose the patterns they’re delivered. This means they can wind up with a box of clothes that is less “chic young mom” and more Pee Wee’s Playhouse. There are 400 new prints apparently designed every day, and LuLaRoe says most patterns are limited to around 5,000 pieces each. When a consultant opens a box, they hope to find a few “unicorns”—the styles everyone wants—among armfuls of duds, like the infamous Dorito pattern.

Research has shown that our brains release more of the pleasure chemical dopamine when we unexpectedly get a reward at a random time. Gambling addicts will run up credit cards and bankrupt themselves chasing that high, continually putting coins into the slot even though it’s become clear that, overall, they are losing. Likewise, LuLaRoe customers will stay glued to Facebook groups and consultants will keep buying inventory they can’t afford in the hope they will stumble across the rarest, most elusive styles.

“Retailers can generate a sense of excitement among consumers because the garments they purchase are unique to them,” says a LuLaRoe spokesperson. “Many retailers report that they use the unexpected nature of the shipment to build excitement among existing and new consumers for their new inventory. This also fosters a sense of cooperation among retailers as retailers will often refer consumers to other retailers to help consumers find the patterns that they seek.”

Sophie says she was often only able to sell five pieces out of every 30-piece order she made. “They said, ‘Be a creator.’ I hate that phrase,” she says. “It means: ‘Figure out how to sell them.’”

Stern was taught ways to unload her unwanted stock on unsuspecting buyers by her group’s leaders. “You have to be creative about how you sell it,” she says. Stern would bundle 10 pairs of leggings together—nine less desirable ones and one unicorn pattern—into “mystery sales,” where the first 10 women to comment “sold” would purchase a random pair, but only one would get the coveted leggings. She feels guilty about using this psychological gambling trick, but it worked.

LuLaRoe’s quality and return policies

In recent months, sellers have claimed that LuLaRoe leggings have a tendency to tear like “wet toilet paper.” The $25 leggings—their most popular item—are manufactured in the US, Vietnam, Guatemala, Indonesia, and China, and are mostly made of a mix of polyester and spandex. Starting in fall 2016, customers started reporting that LuLaRoe’s “buttery soft” leggings were falling apart. Sometimes within just a few hours of wearing them, pinholes would splatter across the fabric, a “blow out” would reveal the wearer’s underwear, or they’d lose all their dye in the wash, leaving them a sad, mottled grey. LuLaRoe has denied that anything was wrong with its leggings, saying that only 1% of its clothing is returned with defects.

That figure may be low because LuLaRoe products used to be so hard to return. For a long time, angry customers couldn’t send back faulty products directly to LuLaRoe: They had to return them to the consultant they purchased them from. Customers are instructed to hand-wash leggings inside out and air-dry them, but that hasn’t stopped the company from getting sued by angry consultants alleging that the leggings are poor quality. Some LuLaRoe retailers have even taken to fat-shaming customers, telling them if the leggings rip, it’s their fault.

Founded in October 2016, the LuLaRoe Defective/Ripped/Torn Leggings and Clothes Facebook group was initially intended for posting pictures of holey leggings. Now it has more than 30,000 members and has become a place for women to share pictures of ugly merchandise, screenshots of vicious consultant behavior, and to upload documents from the numerous lawsuits against LuLaRoe. (At last count, there are nine ongoing legal battles.)

Christina Hinks, an aspiring journalist and the former moderator of the Facebook group, attempted to draw attention to LuLaRoe practices she found problematic. She has been collecting and documenting LuLaRoe issues at her blog, Mommygyver, which went from product reviews to educating readers on the risks of MLMs and inventory loading, revealing fat shaming by consultants, sharing stories of women who claim to have been victimized by LuLaRoe, and posting screenshots and stories of shenanigans by consultants and leaders at the top.

After a slew of complaints, LuLaRoe rolled out a Happiness Policy in April 2017, which states that customers can get a credit, cash refund, or replacement pair (but not the same pattern) for defective leggings purchased between January 2016 and April 2017. However, many are saying their refund checks have still not been issued, even though they were told they’d arrive several weeks ago.

Consultants and clients say the clothing’s quality has been going back up, but the PR damage has been done. Shoppers are becoming wary—and wondering why they’re not buying leggings that don’t rip on the first wear for $7.99 at Wal-Mart instead.

Getting out

With their leggings falling apart, parties going dead, and debt ballooning, going-out-of-business (GOOB) sales have proliferated. As a result, potential customers now know they don’t have to pay retail price for products: They can just type “LuLaRoe going out of business” into Facebook and find heavily discounted items. This makes it even harder for the consultants still in the game to make money, as they are competing with women who are undercutting their prices in an attempt to squeeze every last penny out of their remaining inventory.

These sales go against company policy. While a LuLaRoe spokesperson says sellers are “free to set their own sales prices for the LuLaRoe products they sell,” they don’t allow you to actually advertise those prices: “Out of fairness to all retailers, they are not allowed to advertise prices below MAP (Minimum Advertised Prices). LuLaRoe encourages retailers not sell product below MAP as MAP ensure that the LuLaRoe brand maintains a consistent level of value and fairness that benefits all Retailers. Advertising prices below MAP violates the agreement between retailers and LuLaRoe.” If caught, sellers are ostracized by the consultant community for diminishing the LuLaRoe brand, and some have claimed to be locked out of their point-of-sale systems.

Stern decided to get out after she realized she had $20,000 in unsold wholesale inventory sitting in her living room. “It clicked for me that if you order 30 items, they send you 10 quick movers and the rest sit. It’s a false sense of actually being successful,” she says. “I noticed all these people started going out of business. I started getting scared that my inventory would be worth nothing, and I would be stuck with $8,000 on my credit card.”

Thankfully, getting out is easier than it used to be—sort of. LuLaRoe has started providing free shipping so that consultants who want to leave can return their inventory and get back what they paid, as long as those items are in perfect condition and in their original packaging. This sounds reasonable—except that retailers generally have to unbox, hang, and photograph each item in order to have a shot at selling it, meaning a lot of their unsold inventory isn’t eligible for a refund.

But one woman’s trash may be another woman’s treasure. New consultants are reporting getting boxes full of old merchandise that appears to be from merchants who went out of business—the ugly stuff others couldn’t sell. “While LuLaRoe may resell some inventory returned in original packaging and in new condition to its employees in its company store,” LuLaRoe CMO Lyon says, “LuLaRoe prefers that product that is returned in original packaging and in new condition be used for donations or giveaways only.” Consultants dispute that claim, posting pictures of “new” merchandise with old patterns and tags that have been marked up by other consultants.

In April, Stern quietly put all her inventory on sale for 25% off, paid off her credit-card debt, and got out. She’s an example of someone who rode the wave and managed to leave before wiping out entirely. She has now started a new company selling leggings using the same skills she learned from selling LuLaRoe—without the binding policies, and with an added charity element. She’s one of the fortunate ones. But what about the rest?

The winners and losers

What made Nicole Haas so prosperous, but nearly ruined Sophie, Kayla, Ashley, and thousands of other women just looking for a small piece of the apple pie?

Perhaps the successful consultants are right: It’s all about enthusiasm. Perhaps some people don’t succeed because they don’t drink the Kool-Aid. Perhaps it’s about believing that leggings printed like hotel carpets are beautiful to someone. Perhaps you think that a thin polyester dress you could get for $15 in a chain store is worth $60 if you buy it from a friend. Perhaps it’s about having no qualms hawking clothes to people who struggle to afford them, or signing women up underneath you while you struggle yourself.

For a portion of independent retailers, LuLaRoe is to economic opportunity as Goop is to wellness: It’s for ladies who already have it all. The ability to throw down $12,000 to start a LuLaRoe business and work 30 hours a week sometimes comes from a place of privilege, not desperation. Some mothers who are just looking for a hobby have husbands whose salaries are already high enough to support their families. “I felt like I was trying to keep up with the Joneses to stay in business against these other consultants who can afford to drop a $500 order every few days,” Ashley says.

This isn’t a story about leggings, however. It’s not even a story about LuLaRoe. This is the story of rural and suburban disenfranchisement and the MLMs that offer desperate American women a chance at clawing their way out. They’ve become part of the fabric of suburban America, as cherished and inevitable as barbecues and the county fair. Regional newspapers are rife with announcements for fundraisers for children with cancer and elementary-school fetes that promote LuLaRoe pop-up shops. Not buying a pair of leggings can be read as being unsupportive of your friends—or not chipping in for a local kid’s chemotherapy. It’s a genius manipulation of rural and suburban American societal norms.

But even if LuLaRoe were to go out of business tomorrow, another MLM pushing scented candles, jewelry, or kitchen products would rise up to take its place. “The regulators cannot keep up with these companies,” Brooks says. “There are so many of them. When one company blows up, the founders and high-level distributors move on to another company, and it goes on and on.” At best, LuLaRoe is a company that grew too fast; at worst, it consciously preyed on business-naïve communities eager for a sense of self-sufficiency.

Small-town America is built on the concept of community, meaning the psychological guilt games MLMs play are their most effective selling tool. Even Christina Hinks of Mommygyver has started positively reviewing other MLMS again, directing her readers to join consultant Facebook groups and helping MLMs with market research. Like America’s systemic class bias, it’s hard to escape.

“People need to be warned about this company now,” one anonymous woman said in a Facebook message to me in April. When I followed up a few days later, she had changed her mind. “I actually onboarded Monday with Agnes & Dora, another direct-sales clothing company. And as part of their policy and procedures, I cannot speak badly of another company.”

Wish her luck.