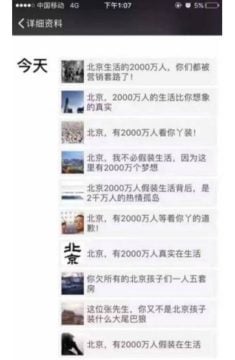

A beautiful essay critiquing the “fake lives” of Beijingers is blocked after lighting up Chinese social media

An online essay titled “Beijing Has 20 Million People Pretending to Have a Life Here” (“北京,有2000万人假装在生活,” full English translation here) by Chinese writer and blogger Zhang Wumao (张五毛) became a viral hit on WeChat and Weibo after it was published on the author’s WeChat account on July 23.

An online essay titled “Beijing Has 20 Million People Pretending to Have a Life Here” (“北京,有2000万人假装在生活,” full English translation here) by Chinese writer and blogger Zhang Wumao (张五毛) became a viral hit on WeChat and Weibo after it was published on the author’s WeChat account on July 23.

The essay is a witty yet powerful critique of Beijing and its residents. Over the last decade, and especially over the past few years, Beijing has undergone enormous changes. The city is expanding, high-rise buildings are mushrooming, while old hutong areas are bricked up and familiar neighborhoods demolished for the sake of the city’s metamorphosis into an “international metropolis.”

According to Mr. Zhang, the city’s rapid transformation has turned it into a place with no identity, a place that nobody can call home. The essay argues that Beijing has been overrun by migrant workers or waidiren (外地人, “people from outside the city”), and that these “outsiders” have turned China’s capital into a place with staggering house prices and heavy traffic that lacks soul. The city no longer really belongs to native Beijingers, Zhang writes, as they cannot even recognize their old neighborhoods anymore.

The essay describes how Beijing has become so big, so full, and so expensive, that life has virtually become unsustainable. The result of Beijing’s transformation, according to the post, is that its residents, both locals and immigrants, just “pretend to live there,” leading “fake lives.”

Zhang Guochen

Zhang Wumao, whose real name is Zhang Guochen (张国臣), is an author born in the early 1980s. He is from Luonan, Shaanxi, and came to Beijing at the age of 25 in 2006. A year later he started blogging. He previously published the novels Spring is Burning (春天在燃烧) and Princess’s Tomb (公主坟).

Zhang’s online essay about Beijing spread like wildfire on WeChat and Weibo on July 23. It was viewed over 5 million times within an evening and soon became a trending article on WeChat. It triggered wide debate across Chinese social media on the lives of people in Beijing.

On July 24 and 25, the essay was also republished by various Chinese media, including Tencent News, iFeng, and Sohu.com.

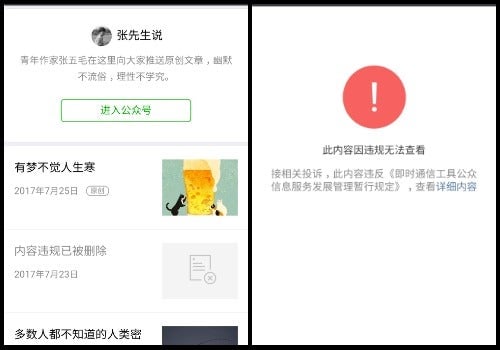

But on July 25, the full text was removed from all social media accounts and Chinese online news sites. Its hashtag on Weibo (#北京有2000万人假装在生活#) is now no longer accessible.

The article also disappeared from Zhang’s WeChat account.

On Quora-like discussion platform Zhihu.com, one person said (link in Chinese) the essay was destined to become a hype: “This is a typical Wechat viral article. It ridicules Beijing + it talks about migrant workers + real estate market + and state of life. As it contains all of these elements in one article, the author just intended for this to become a hit.”

A sensitive essay

Zhang’s essay is divided into five parts. In the first part, he explains that Beijingers often seem inhospitable; the city is so huge and congested that people simply cannot find the time to see their friends in other parts of the city.

Beijing is really too big; so big that it is simply not like a city at all. It is equivalent to 2.5 times Shanghai, 8.4 times Shenzhen, 15 times Hong Kong, 21 times New York, or 27 times Seoul. When friends from outside come to Beijing, they think they’re close to me. But actually, we’re hardly in the same city at all.

For 10 years, Beijing has been controlling housing, controlling traffic, and controlling the population. But this pancake is only getting wider and bigger, so much that when a school friend from Xi’an calls me to say he’s in Beijing and I ask him where he is, he tells me: “I am at the 13th Ring.” Beijing is a tumor, and no one can control how fast it is growing; Beijing is a river, and no one can draw its borders. Beijing is a believer, and only Xiong’an can bring salvation.

The second part, which is titled “Beijing actually belongs to outsiders” (北京其实是外地人的北京), claims that Beijing is one of the most beloved cities in China because of its rich cultural heritage and long history, but this is something that is only of value to people from outside the city.

In the 11 years since I’ve come to Beijing, I have been to the Great Wall 11 times, 12 times the Imperial Palace, 9 times to the Summer Palace, and 20 times to the Bird’s Nest. I feel emotionless about this city’s great architecture and long history. … Going into the Forbidden City, I only see one empty house after the other—it’s less interesting than the lively pigsties we have in my native village.

Upon mentioning Beijing, many people first think of the Palace Museum, Houhai, 798; they think of history, culture, and high-rise buildings. Is that a good thing or a bad thing? It’s good! Does it make us proud? It does! But you can’t make food out of these things. What Beijingers increasingly feel is the suffocation of the smog and the high cost of housing. They cannot move, they cannot breathe.

He then goes on to mock the old residents of Beijing, who still have the upper hand in the real-estate market despite the flood of new immigrants, all owning “five-room houses.” The old Beijingers lead very different lives from the migrant workers, who are caught in a negative spiral of hard work, no social life, and finding a place to settle down.

In Beijing, the migrant workers, who have no real estate from previous generations, are destined to be trapped in their house for life. They strive for over a decade to buy an apartment the size of a bird cage; then spend another decade struggling to get a house that has two rooms rather than one. If that goes well, congratulations, you can now consider an apartment in the school district.

With a house in the school district, children can attend Tsinghua or Peking University. But Tsinghua graduates will still not be able to afford a room in that district. They will then either need to stay crammed together in the old shabby family apartment, or start from scratch, struggling for another apartment.

In the final part of the essay, however, Zhang shows his sympathy for the old residents of Beijing:

I once took a taxi to Lin Cui Road. Because I was afraid the driver wouldn’t know the way, I opened the navigation on my phone to help him find the way. He said he did not need the navigation because he knew that place. There was a flour mill there 30 years ago, he said, it was demolished 10 years ago, and they built low-income housing there. I asked him how he knew this so well. “That used to be my home,” he said, the sorrow showing in his face.

I could hear nostalgia and resentment from the driver’s words. For Beijing’s new immigrants, the city is a distant place where they can’t stay; for Beijing’s old residents, the city is an old home they can’t return to.

We, as outsiders, ridicule Beijing on the one hand, while on the other hand, we cherish our hometowns. But in fact, we can still go back to our hometown. It is still there. … But for the old Beijingers, there really is no way to go back to their hometown. It has changed with unprecedented speed. We can still find our grandfather’s old house. The majority of Beijingers can only find the location of their old homes through the coordinates on a map.

He concludes his article by highlighting the recent demolishment of old Beijing shops and restaurants, saying that the city is being renovated but is becoming less livable.

Those who chase their dreams of success are now escaping [Beijing]. They’re off to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, or the west coast of the United States. Those who’ve lost hope of chasing their dreams are also escaping. They return to Hebei, the northeast, their hometowns.

He ends by writing: “There are over 20 million people left in this city, pretending to live. In reality, there simply is no life in this city. Here, there are only some people’s dreams and everybody’s jobs.”

Chinese media responses

Despite censorship of the actual text, Zhang’s essay is widely discussed by Chinese official media.

The essay “Beijing Has 20 Million People Pretending to Live There” is a viral hit but is not approved of. There really is such a thing as the “Big City Disease,” and we do not need to pretend as if people in first-tier cities are not struggling and facing hardships. But in Beijing, both locals and outsiders are alive and kicking; they are all the more real because of their dreams. Making a living is hard, but it is the days of watching flowers blossom and wilt that are full of life. The city and its people don’t have it easy, but they have to show some tolerance for each other and then they can both succeed.

Xinhua News Agency also published a response to the article titled: “Lives in the City Cannot Be Fake” (“一个城市的生活无法“假装“). Lashing out against Mr. Zhang, it wrote that: “Beijing has no human warmth, Beijing is a city of outsiders, old Beijingers can’t go back to their city—behind every one of these sentences is not the ‘fakeness’ of Beijing, but the clamor of the author’s emotions about ‘coming to Beijing.'”

State broadcaster CCTV (@央视新闻) also responded to the essay on Weibo, saying:

Over the past few days, the essay “Beijing Has 20 Million People Pretending to Live There” has exploded on the Internet, but how the text portrays the contrast between old Beijingers and new immigrants is exaggerated, and it polarizes the relationship between native Beijingers and outsiders. In reality, Beijing is not as cold as it is described in the essay. Everyone already knows that it’s not easy living in a big city. The future of Beijing is in the hands of competent, daring, and hardworking people who pursue their dreams.

A storm of debate

On social media, many netizens commented on the state media’s responses to Zhang, saying they were tired of the repeated emphasis on “people’s dreams.” One person said: “My belly is empty, what are you talking about dreams for?! Dreams cannot guarantee our most basic needs for survival.”

Many people on Weibo and QQ (link in Chinese) also applauded Zhang’s essay for being “well-written,” “honest,” and “real.”

But there are also those who do not agree with the essay and take offense at how it describes Beijingers leading “fake” or “pretense” lives. A Beijing resident nicknamed Little Fish (@小小的爱鱼) commented: “What on earth gave him the courage to speak on behalf of 20 million Beijing people? I am one of these 20 million people, and sorry, but my life is not fake—I am living it.”

“I work overtime until 9pm, then take the bus and subway and won’t arrive home before 23:38, then quickly rinse my face and brush my teeth and roll into bed. But it’s still life. What life and being alive is all about ultimately is a personal issue,” said another netizen from Beijing (link in Chinese).

“Mr. Zhang,” one angry commenter wrote, “you can leave this cold and big city of Beijing, and go back to your ‘real’ life in that pigsty of yours that’s supposedly more imposing than the Forbidden City.”

The recent hype surrounding Zhang’s essay somewhat resembles the overnight buzz over the autobiographical essay of Beijing migrant worker Fan Yusu. That essay also described various hardships in the lives of Beijing migrant workers.

Fan Yusu’s essay and posts related to it were also taken offline after several days when discussions on the account spread across Chinese social media.

Zhang’s hit essay shows that the combination of writing about migrant workers, Beijing, real estate, and state of life is indeed bound to attract wide attention and debate on social media. Although it is also a recurring topic in China’s official media, those channels prefer to focus on the idea of hardworking people who pursue their (Chinese) dreams, rather than to spread a narrative about people living “fake lives” in a cold city.

One commenter says: “Whether you fake it or you try hard, it’s all okay: This is Beijing. It’s not livable, but you sure can make a living.”

Special thanks to Diandian Guo.

This story originally appeared on What’s on Weibo. Follow editor-in-chief Manya Koetse and What’s on Weibo on Twitter.