The new FDA plan for regulating cigarettes echoes a tobacco industry idea from the 1950s

The US Food and Drug Administration today announced it will develop new standards reducing nicotine in cigarettes. The goal is to make cancer sticks less addictive, which in turn should minimize the number of long-term smokers, and the number of Americans who die of smoking-related diseases.

The US Food and Drug Administration today announced it will develop new standards reducing nicotine in cigarettes. The goal is to make cancer sticks less addictive, which in turn should minimize the number of long-term smokers, and the number of Americans who die of smoking-related diseases.

“The overwhelming amount of death and disease attributable to tobacco is caused by addiction to cigarettes—the only legal consumer product that, when used as intended, will kill half of all long-term users,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb. “Envisioning a world where cigarettes would no longer create or sustain addiction…needs to be the cornerstone of our efforts.”

The FDA is thinking ahead, it says, and believes millions of premature deaths could be prevented by making cigarettes less habit-forming.

Interestingly, cigarette manufacturers have been onto this idea for quite some time. A British American Tobacco company report stated in 1959 that “to reduce the nicotine per cigarette as much as possible and thus satisfy the trend of consumer demand…might end in destroying the nicotine habit in a large number of consumers and prevent it ever being acquired by new smokers.”

That document surfaced in an epic lawsuit, State of Minnesota v. Philip Morris, which targeted five tobacco companies and alleged a 50-year conspiracy to defraud Americans about the hazards of smoking, stifle development of safer cigarettes, and target children as new customers. The trial revealed that Big Tobacco had long known of the dangers of smoking and minimized risks to consumers in order to maximize profits. The parties agreed to settle the litigation with a $6.5 billion settlement in 1998.

An article that year in the Journal of the American Medical Association, titled ”Prying open the door to the tobacco industry’s secrets about nicotine,” concluded that cigarette manufacturers had long acknowledged, if only internally, that “nicotine is an addictive drug and cigarettes are the ultimate nicotine delivery device; that nicotine addiction can be perpetuated and even enhanced through cigarette design alterations and manipulations; and that ‘health-conscious’ smokers could be captured by low-tar, low-nicotine products.”

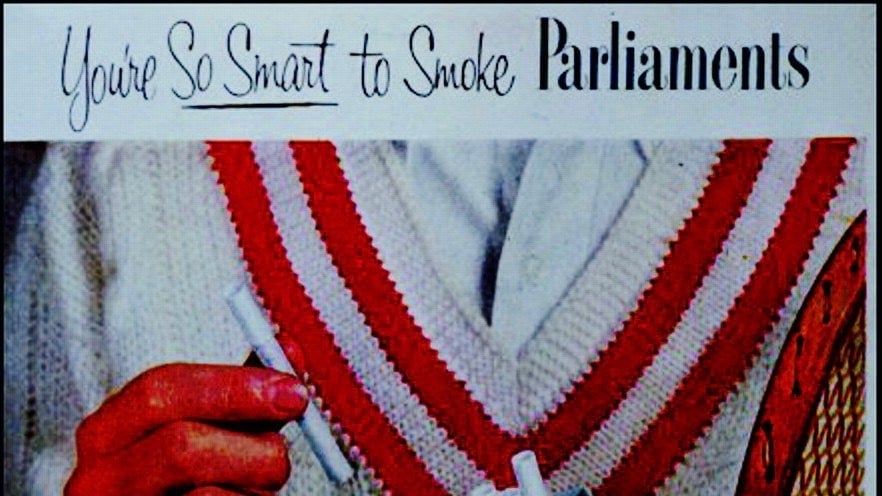

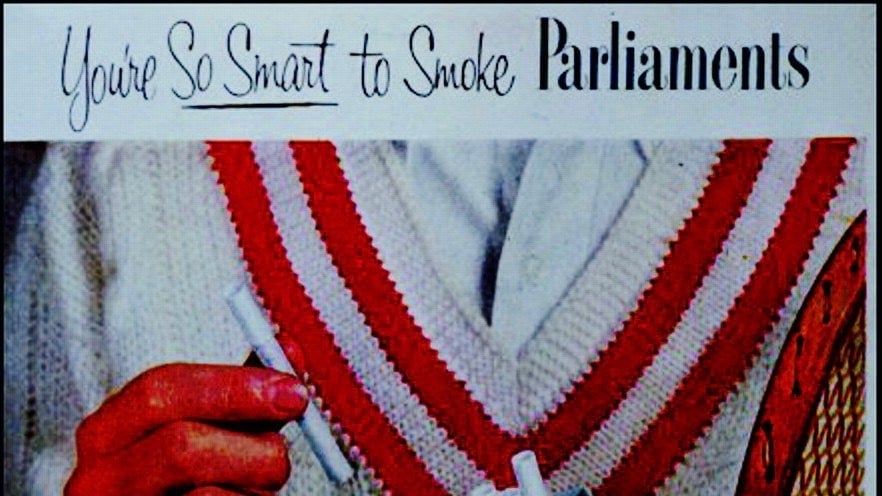

Tobacco companies began working on “safer” cigarettes half a century ago. It was a little awkward, though, as developing “healthier” cigarettes could be seen as a roundabout way of saying smoking is no good; marketing a “safer” product would present a public-relations conundrum.

But it was obviously a very lucrative possibility. The Minnesota trial also surfaced documents from Phillip Morris executives saying—as early as 1958—that ”the first company to produce a cigarette claiming a substantial reduction in tars and nicotine…will take the market.”

Now, the FDA is planning to make low-nicotine cigarettes the new standard. Although the intention behind this are no doubt admirable, the plan does present an ethical dilemma—and a possible hitch—cigarette makers have long considered. As a 1978 document from the Lorillard Tobacco company addressing safer cigarettes asks, “Is it morally permissible to develop a safe method for administering a habit forming drug when, in so doing, the number of addicts will increase?’”