Setting goals around tasks, not outcomes, is the best way to improve performance, a study shows

The importance of setting goals is well-established.

The importance of setting goals is well-established.

Athletes routinely use goals as motivation. Corporate boards set goals for CEOs to create incentives. Scarcely a middle-school assembly or motivational speech goes by without a speaker exhorting the audience to set goals.

But some goals are more effective than others. A new study of US undergraduates suggests students who set task-based goals—such as taking a certain number of practice tests—will outperform students who set performance-based goals, such as a letter grade for the course. The findings, from economics professors at the University of California at Irvine, Purdue University, and the University of Florida, have been released in a working paper (pdf) by the National Bureau of Economic Research, and so hasn’t been peer reviewed yet.

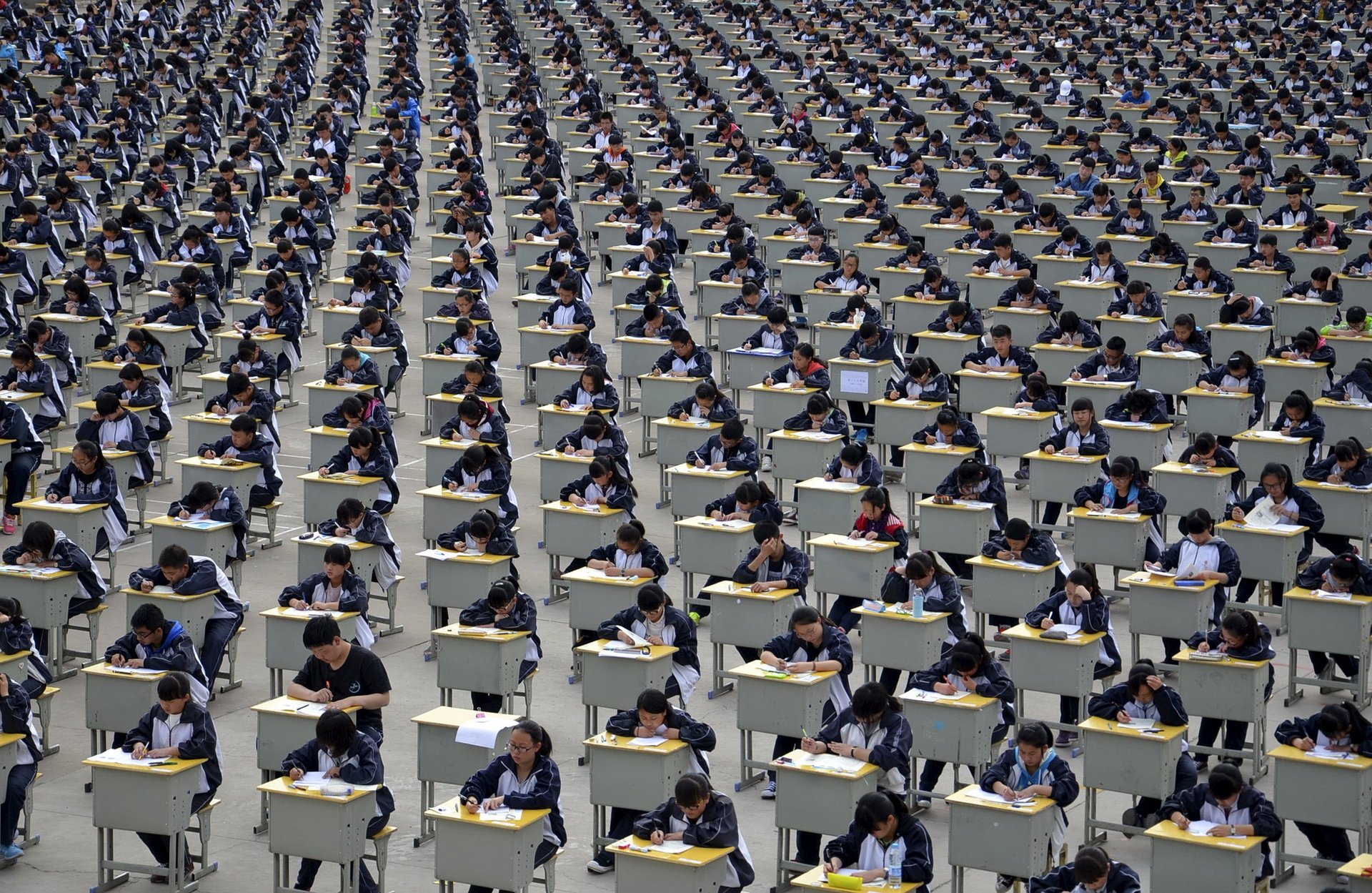

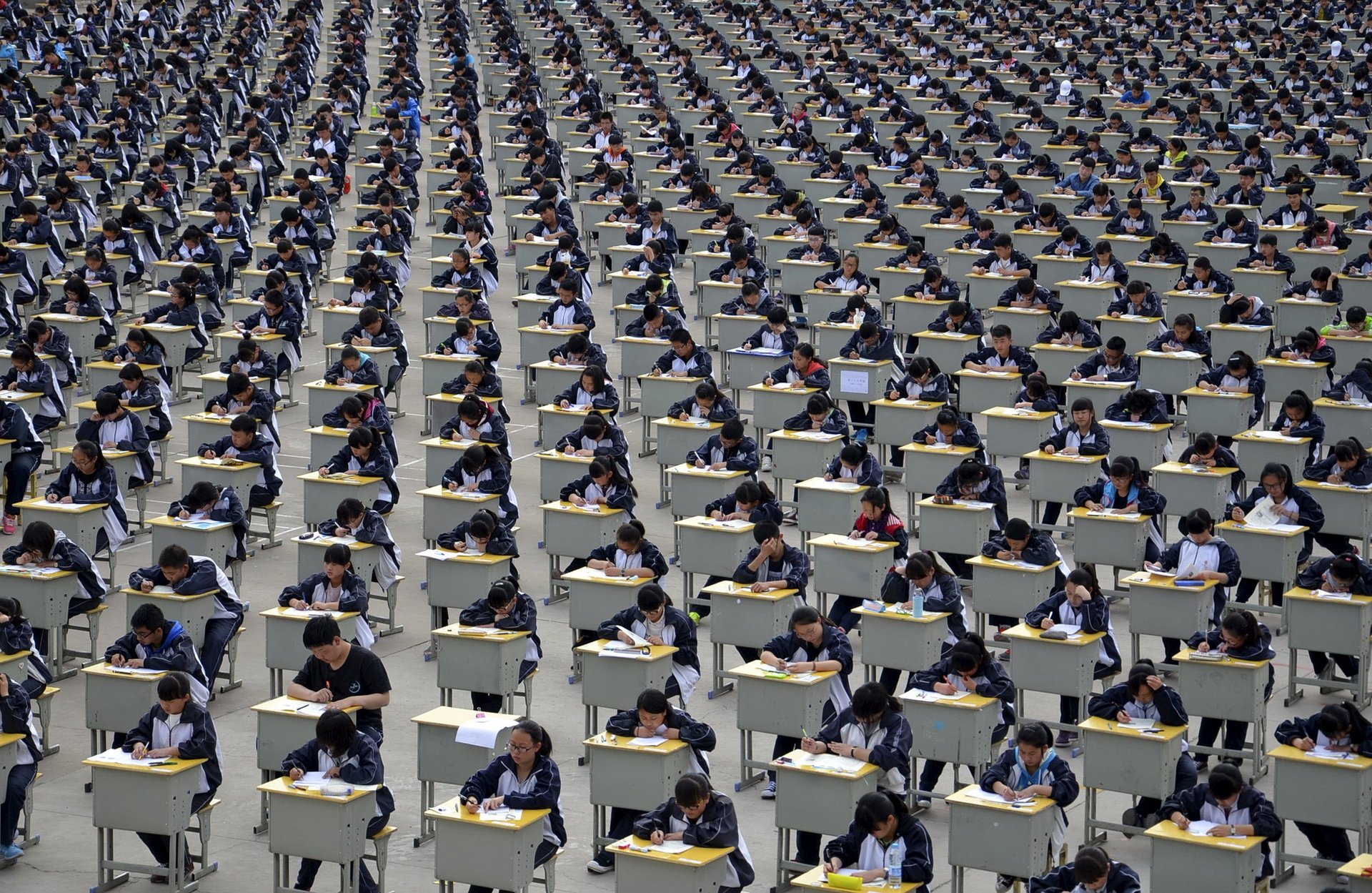

The researchers ran two experiments with a total of nearly 4,000 students in an introductory course at a public university. In one, students who set a goal of taking a fixed number of online practice tests were 5% more likely to get a B+ grade or better than those in a control group with no set goal. In the other experiment, students who set a letter grade as a goal were no more likely to get a B+ or better than those who set no goals.

Because the researchers didn’t directly test the two styles of goal setting against the other, they can’t say with certainty that task goals are superior to performance goals, but they do know they work, said UC Irvine’s Damon Clark, one of the study’s authors.

The study suggests three possible reasons why task-based goals could work better than performance goals. First, the students may have been more attuned to the present than future, so a goal where the results won’t be realized for months would have less urgency. Second, students are likely overconfident of their abilities, and so they may feel they are doing the work to meet their longterm goal without realizing they’re falling short. Lastly, they said, most students tend to view the relationship between effort and performance as inherently random, “which makes performance-based goals risky and therefore less effective.”

Male students, in particular, did better with task-based goals. The researchers argue that men are more “present-biased,” and less able to direct themselves toward long-term goals.

The study has clear implications about how to better motivate college students, but it also holds lessons for the rest of us. Intuitively, most of us know that small, bite-sized goals are easier to attain than big ones, yet we’re often still focused on results i.e., setting a goal to close two sales a week. It’s better to focus on accomplishing the tasks that will yield the results, such as making 10 sales calls a day. In theory, if you put in the work, the results will follow.