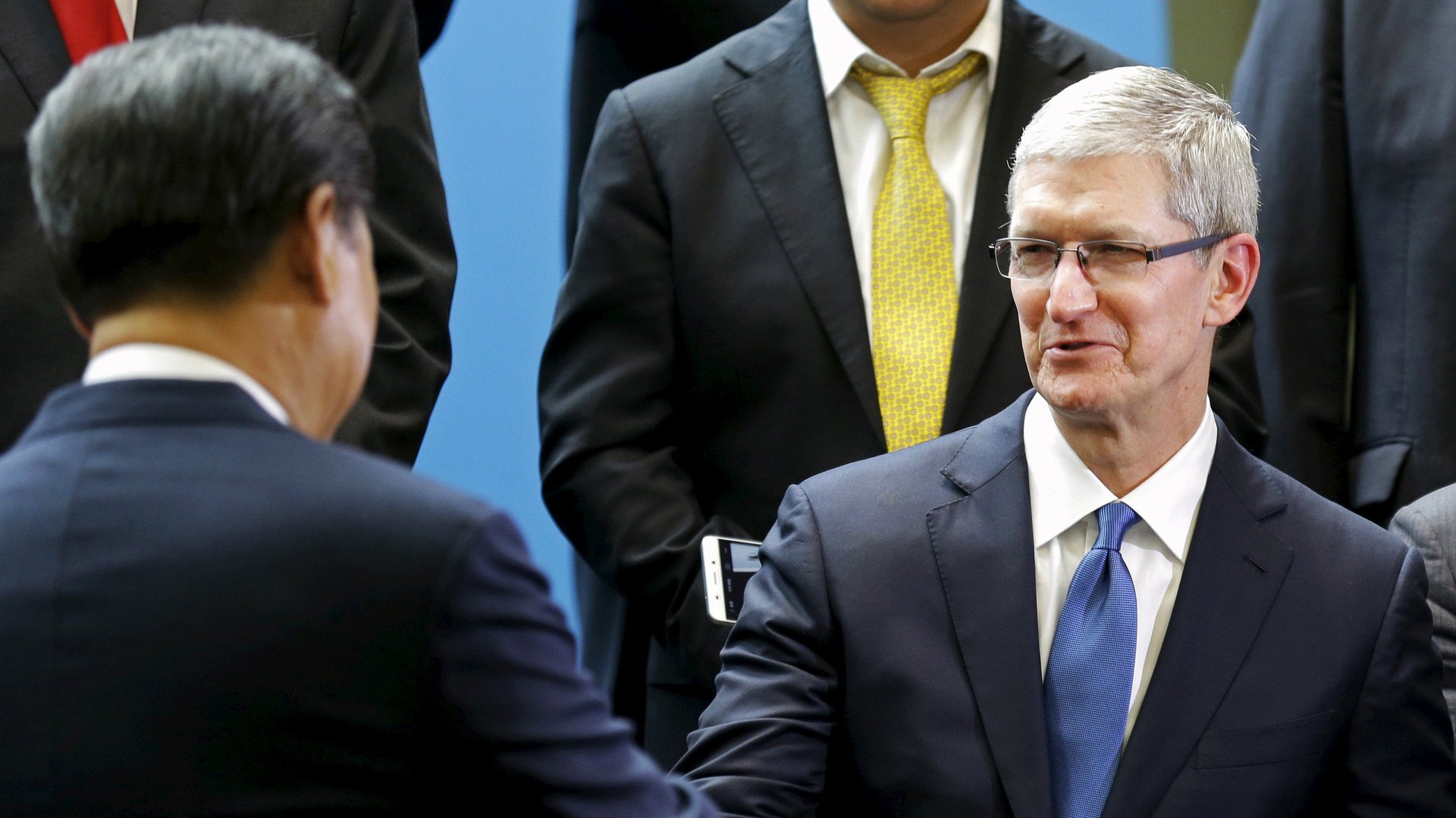

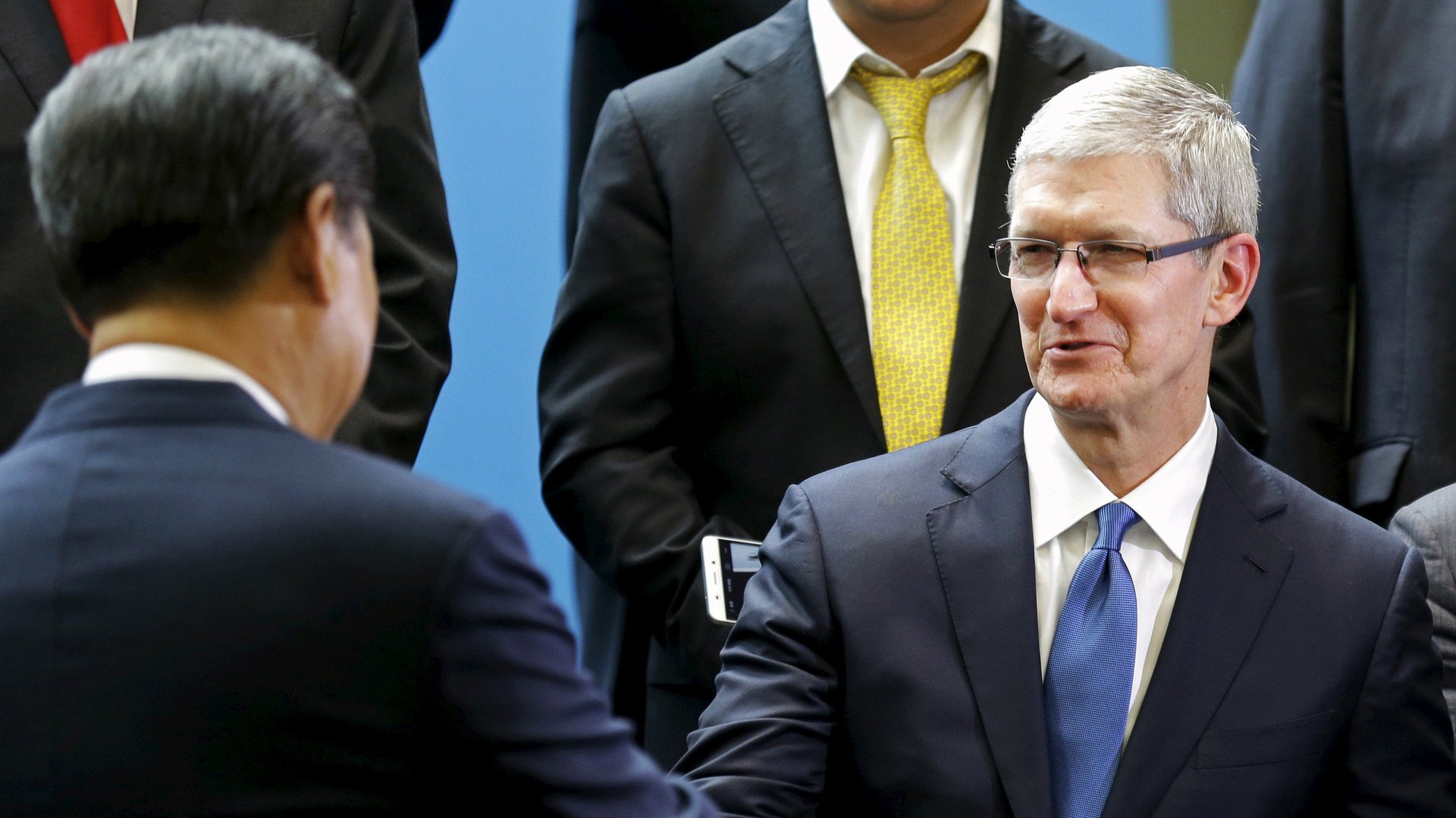

Tim Cook is defending Apple’s removal of VPN apps from its Chinese app store with a familiar refrain

Over the weekend Apple removed dozens of virtual private network (VPN) apps from its Chinese app store, depriving many users of tools that are critical to jumping the country’s Great Firewall. The move marked a major capitulation to China’s censorship regime, and follows similar requests to block various apps and content in the country.

Over the weekend Apple removed dozens of virtual private network (VPN) apps from its Chinese app store, depriving many users of tools that are critical to jumping the country’s Great Firewall. The move marked a major capitulation to China’s censorship regime, and follows similar requests to block various apps and content in the country.

When news of the removal first broke, Apple remained relatively tight-lipped, issuing only a brief statement through its press team confirming the decision. According to one compilation, some 200 apps that allow users to access sites blocked by China appear to have been removed, including services from major providers like Express VPN.

But in the middle of Apple’s earnings call for its most recent quarterly financial report, Tim Cook addressed the issue in more detail. And his defense falls back on a familiar refrain for Western businesses wrestling with the political ramifications of doing business in China. His statement reads:

Let me just address that head on. The central government in China back in 2015 started tightening the regulations associated with VPN apps, and we have a number of those on our store. Essentially, as a requirement for someone to operate a VPN, they have to have a license from the government there. Earlier this year, they began a renewed effort to enforce that policy, and we were required by the government to remove some of the VPN apps from the App Store that don’t meet these new regulations. We understand that those same requirements are on other app stores, and as we checked through that, that is the case.

Today there are actually still hundreds of VPN apps on the App Store, including hundreds by developers that are outside China, and so there continues to be VPN apps available. We would obviously rather not remove the apps, but like we do in other countries, we follow the law wherever we do business. And we strongly believe that participating in markets and bringing benefits to customers is in the best interest of the folks there and in other countries as well. And so we believe in engaging with governments even when we disagree.

And in this particular case, now back to commenting on this one, we’re hopeful that over time the restrictions that we’re seeing are loosened because innovation really requires freedom to collaborate and communicate, and I know that that is a major focus there. And so that’s what we’re seeing from that point of view.

Some folks have tried to link it to the U.S. situation last year, and they’re very different. In the case of the U.S., the law in the U.S. supported us, which was very clear. In the case of China, the law is also very clear there. And like we would if the U.S. changed the law here, we’d have to abide by them in both cases, that doesn’t mean that we don’t state our point of view in the appropriate way. We always do that. And so hopefully that’s a little bit probably more than you wanted to know, but I wanted to tell you.

By “the case of the US,” Apple is referring to the company’s successful fight against the FBI’s request to unlock the iPhone of one of the shooters in the 2015 San Bernardino, California, terrorist attacks.

Cook’s lengthy statement is an excellent example of the talking points Western CEOs turn to when justifying questionable political choices, in China or elsewhere. They go something like this—reiterate that the law is the law (“we follow the law wherever we do business”), highlight that the company believes the benefits of engagement outweigh the costs of withdrawal (“we strongly believe that participating in markets and bringing benefits to customers is in the best interest of the folks there and in other countries as well”), and then gently voice opposition to the policy, just enough to appease the finger-waggers (“we’re hopeful that over time the restrictions that we’re seeing are loosened because innovation really requires freedom to collaborate and communicate”).

LinkedIn, which has offered a censored version of its social-networking site since 2014, once said (paywall) that while it “strongly support[s] freedom of expression,” it “would need to adhere to the requirements of the Chinese government in order to operate in China.” Mark Zuckerberg, meanwhile, has defended his company’s compliance with censorship requests in countries like Pakistan and Thailand by arguing that it serves citizens’ best interests to “continue operating” rather than risk getting shut down for not blocking content.

Of course, just because this refrain is common doesn’t mean it is insincere. Cook and other executives can plausibly argue that iOS, in spite of following censorship orders, can serve Chinese consumers better than Android because it is more secure, and that those qualities alone justify sticking around in spite of political qualms. Apple commentator John Gruber, for example, notes that Facetime and iMessage, which remain accessible in China, effectively give millions of Chinese consumers easy access to end-to-end encrypted chat apps.

If Apple stood up to Beijing over the content it makes available in China, it would be unusual—but it wouldn’t be the first company to do so. In 2010, Google effectively withdrew from China’s consumer-facing market when it shutdown its Google.cn, a censored search engine its executives felt deeply ambivalent about. Google’s decision followed a hack of its systems originating in China that appeared to be aimed at accessing the Gmail accounts of Chinese activists. In a statement just before its official “exit” from China, Google spokesperson David Drummond described getting burned by the precise compromise that Cook weighs on in his statement.

“We launched Google.cn in January 2006 in the belief that the benefits of increased access to information for people in China and a more open Internet outweighed our discomfort in agreeing to censor some results,” he stated. “These attacks and the surveillance they have uncovered—combined with the attempts over the past year to further limit free speech on the web—have led us to conclude that we should review the feasibility of our business operations in China,” he added.

For Apple, doing anything that would jeopardize its business in China could cause a big blow to its balance sheet and stock price. The company earns almost 20% of its revenue from greater China (which includes Taiwan and Hong Kong). But sales there have been slowing for some time now, and this quarter, the region was once again the only region to suffer from negative year-on-year revenue growth.

Meanwhile, China’s overall smartphone market has reached saturation. That means a return to revenue growth now depends on the kind of transition Apple’s making more broadly, as apps and subscriptions become a growing share of global revenue. Apple has real skin in the China game, and it can’t afford to lose its shirt over politics.