When a business should not follow Steve Jobs’s advice

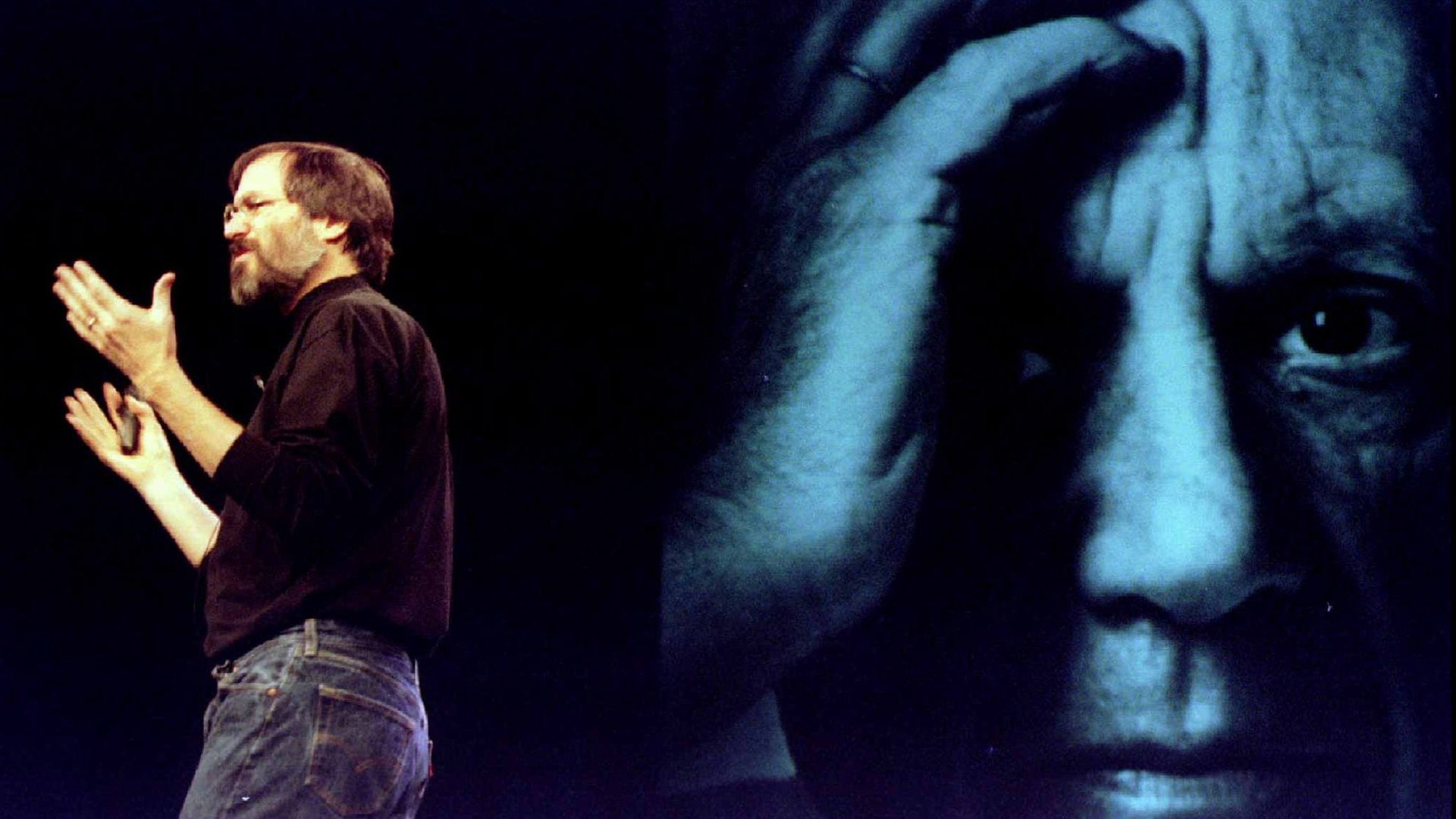

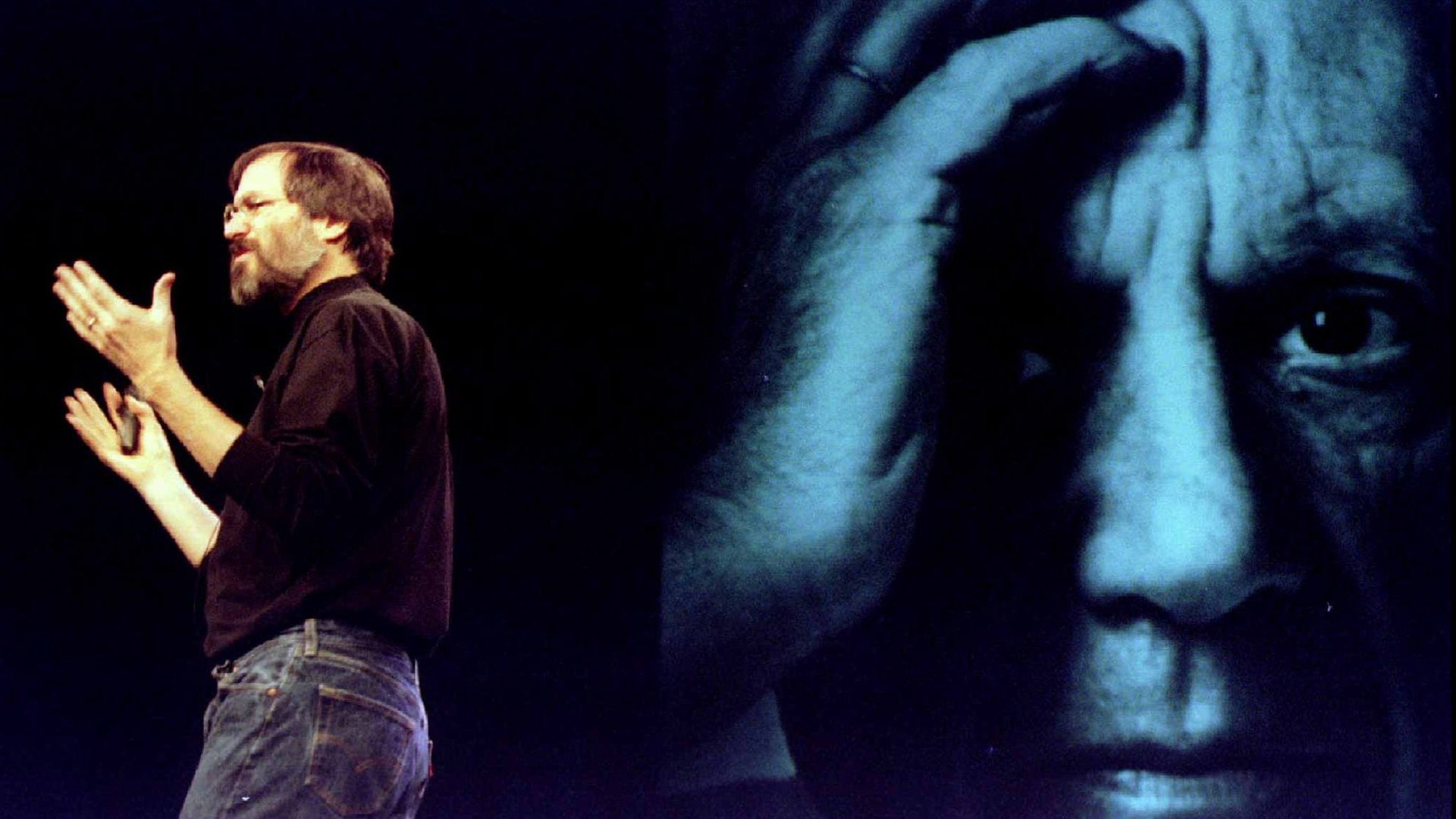

Even before his untimely death, Steve Jobs found his place—or maybe elbowed his way—onto the Mount Rushmore of business gurus, joining Henry Ford, Jack Welch, and Warren Buffett as a management sage.

Even before his untimely death, Steve Jobs found his place—or maybe elbowed his way—onto the Mount Rushmore of business gurus, joining Henry Ford, Jack Welch, and Warren Buffett as a management sage.

But companies that blindly follow his precepts can easily lose their way.

The leaders of Big Ass Solutions, makers of really large ceiling fans and other appliances, were burned when they embraced Jobs’s philosophy of selling customers products they don’t know they want, as CEO Carey Smith recounts in Harvard Business Review.

Jobs famously trusted his gut over market research, believing he knew what was best for users. “A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them,” he told Businessweek in 1998. Jobs was right often enough—he popularized once-unconventional innovations like on-screen graphics, one-button devices, and touch-screen phones—that his disdain for customer preference started to sound like wisdom.

Jobs indeed had an uncanny knack for understanding his customers, but often overlooked is that his successes at Apple were the product of enormous research-and-development efforts, supported by a world-class team of designers and engineers. Every new device or feature, for example, required 10 different prototypes, built to the exacting standards of an Apple final product, giving the company insight into what would and wouldn’t work. Jobs could trust his gut because he had digested all the alternatives.

Big Ass Solutions, on the other hand, rushed into the market for internet-enabled devices, after pouring over research that predicted an explosion in the “internet of things”—one analysis predicted a trillion IoT devices by 2015—and conducted its own market studies. The company’s own surveys indicated that people wanted “automated comfort,” Smith wrote, but “what we overlooked in our excitement at the time was the much smaller percentage of consumers who found an app appealing.”

The company designed fans that could connect to the internet, and be controlled via phone, but still worked conventionally. As it turns out, about half of its customers ignored the new technology, never bothering to create an online account to enable the app. Far from the predicted stampede toward IoT products, Smith notes that only 10% of households have connected appliances, and fewer actually use them.

“Looking back, we were probably guilty of some ‘Jobsian’ thinking, convinced that people don’t know what they want until you show it to them,” and confused the enthusiasm its employees had for the new devices with their wider appeal, Smith wrote.

In the end, most consumers don’t have the patience required to program their ceiling fans; they just want them to look good and work.