The most overlooked market for sex robots is women

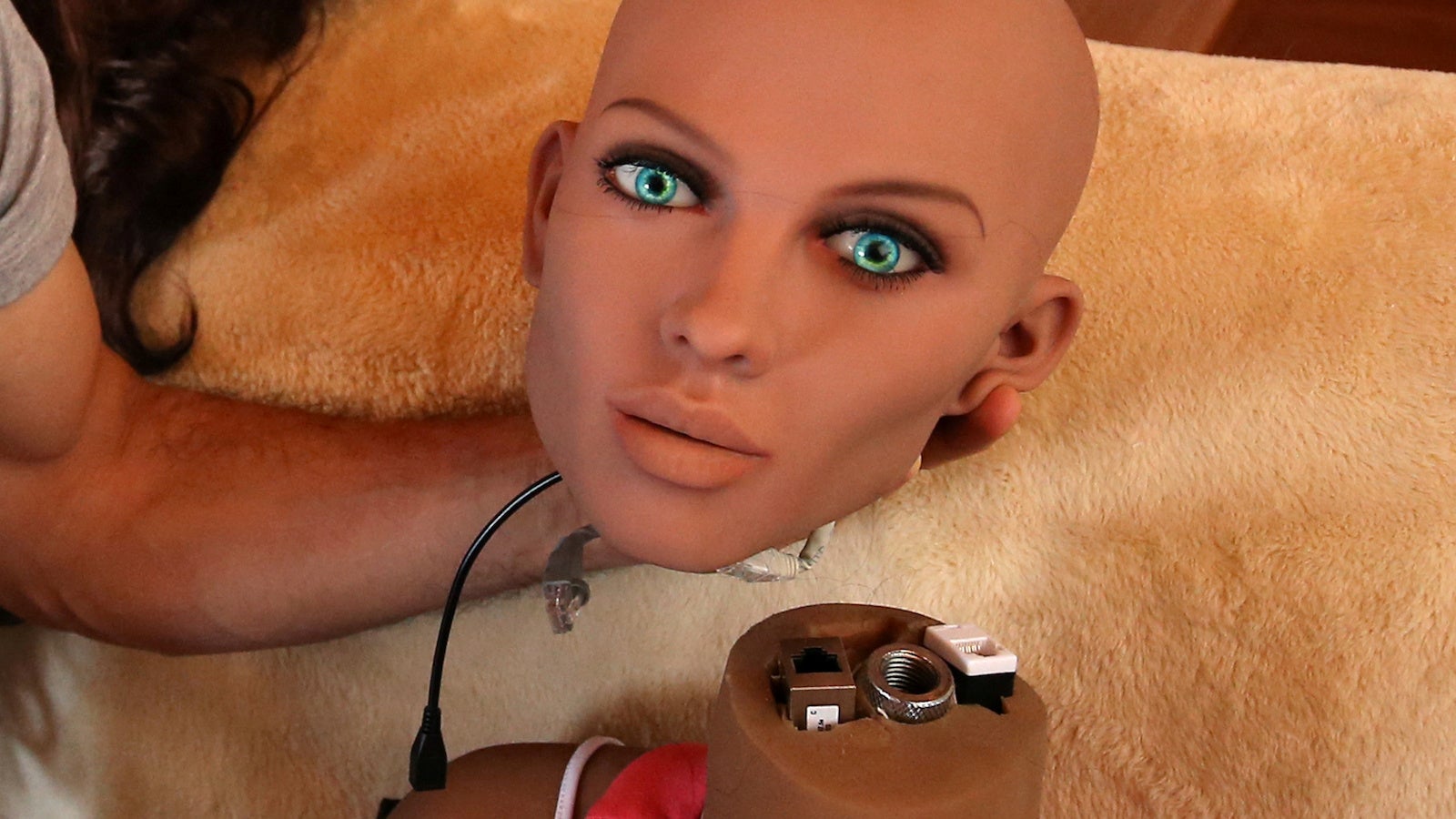

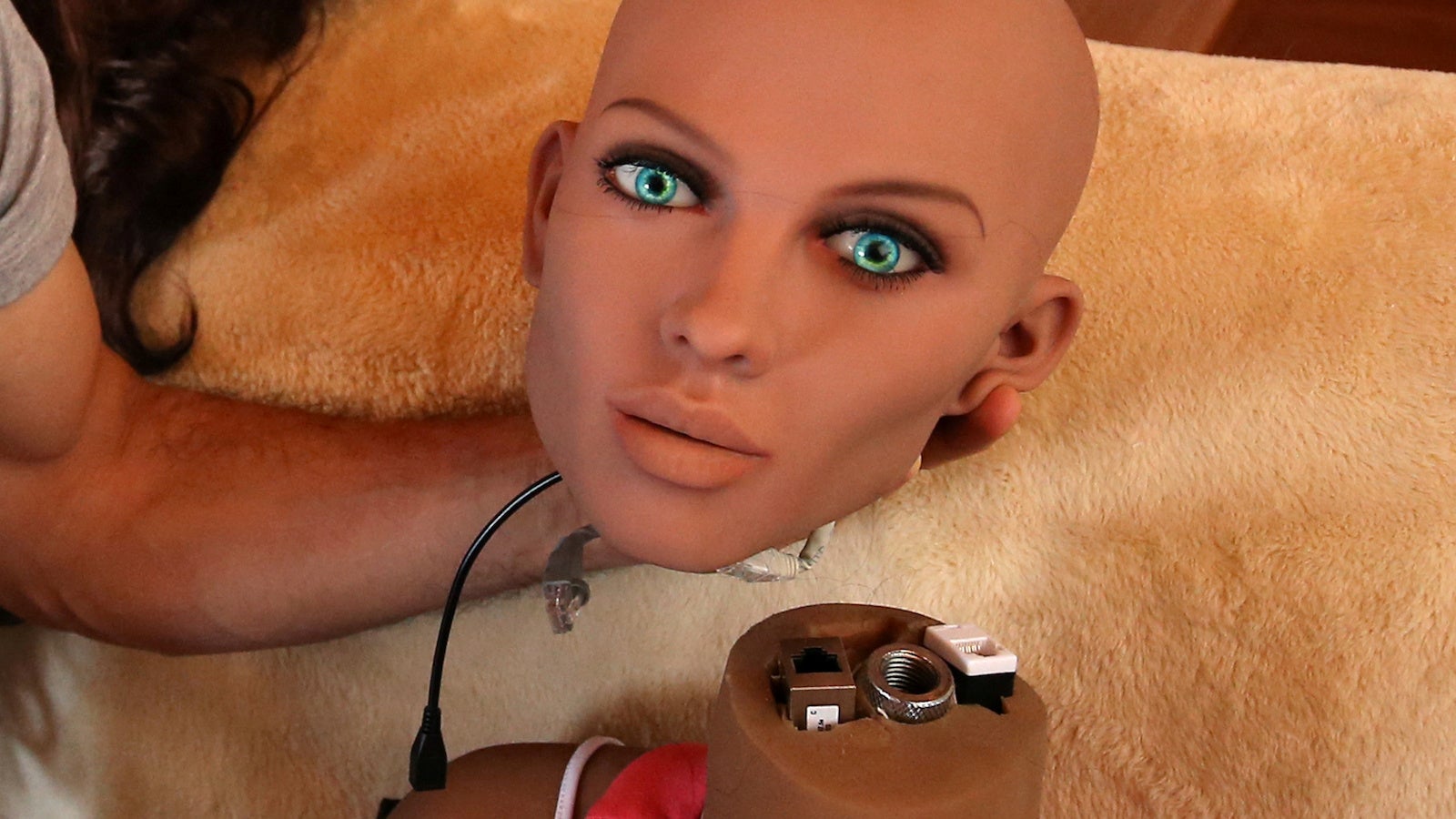

Sex robots, long a staple of science fiction, have begun receiving a lot of real-world attention. Unlike sex dolls, their inanimate counterparts, sex robots blend lifelike silicone with animatronics to simulate movement, and embed their mechanical brains with artificial intelligence to feign conscious behavior. They seek to emulate a real-life partner that is capable of responding and adapting to its partner, not simply a life-size replica to be used—and abused.

Sex robots, long a staple of science fiction, have begun receiving a lot of real-world attention. Unlike sex dolls, their inanimate counterparts, sex robots blend lifelike silicone with animatronics to simulate movement, and embed their mechanical brains with artificial intelligence to feign conscious behavior. They seek to emulate a real-life partner that is capable of responding and adapting to its partner, not simply a life-size replica to be used—and abused.

But where are the sex robots for women?

Simply: There aren’t any. And although a couple of companies claim to be developing male robots, no evidence has substantiated these claims. At first blush, this may not seem too surprising, especially coming from an industry so often criticized for its depiction and objectification of women. However, the sheer size of the sex-tech market—believed to be around $30 billion—would lead you to expect that at least something is being produced for women. Even if only a small fraction of women were interested in the technology, that’s still a very large sum of money for only a sliver of the pie.

Evidence in other areas of the adult industry suggests that quite a large number of women may be just as interested in exploring these technologies as their male counterparts. Though data is—understandably—hard to come by, one study puts sex-toy purchases at an even split between men and women. That means there’s a huge, untapped potential market for sex robots.

Why the gap? The history of technology (the non-sexual type) is largely products made by men, for men. Smartphones often fit uncomfortably in the smaller hands of women, especially some of the newer, larger models. Cars were designed to be safe for men, with seatbelts and airbags much more likely to fail for women. And new artificial hearts are only suitable for 20% of women, as opposed to 86% of men. When questioned by Motherboard as to the development of a smaller model for women, a representative said there were no plans because this “would entail significant investment and resources over multiple years.”

The fact sex robotics relies on developments in artificial intelligence magnifies the problem; the AI field is notorious for its gender bias, even compared to others in the tech industry. Microsoft researcher Kate Crawford decried this as AI’s “White Guy Problem” in an op-ed for the New York Times, and Margaret Mitchell, a former researcher at Microsoft who is now at Google, described AI as a “sea of dudes.” It’s unsurprising, then, that sex robots are being developed largely for straight men.

The gendered headlines are illuminating—“New sex robots with ‘frigid’ settings allow men to simulate rape”; “A rape-able sex robot makes the world more dangerous for women, not less”—but in spite of recent media hype, sex robots are still very much in the early stages of development. Kate Devlin, a lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London, is an expert in sex robotics. She took to Twitter to voice her objection to the media hype: “There are no actual sex robots in production yet—just dolls.” And, as Devlin clarified via email, of those companies that are mixing animatronics and AI with their dolls, the products still appear to be very much in development. “There’s far too much scaremongering,” she said. “We need to debate the ethics—but not from a hyped-up moral standpoint.”

The ability to fake-fornicate with something—“someone”—that can give the illusion of consent has raised a number of moral issues. A report from the Foundation For Responsible Robotics recently examined a number of these concerns: Do sex robots pose a threat to women? Should we allow “rapeable” robots? What about child-size robots?

“What we’re seeing with sex robots is simply an evolution of sex dolls,” Devlin goes on to explain. “We have amazing technology to play with, and yet sex robots are going down the ultrareal humanoid route.” Devlin thinks that this isn’t the correct route to be exploring. Because of the uncanny valley effect, which is the indescribably creepy feeling we get when we interact with a realistic-looking robot, she believes that many people will not want to interact so intimately with what they’re subconsciously aware is just mechanics and silicon. Because of this, Devlin believes the current direction of sex-robot production is “doomed to fail.”

Instead of just trying to replicate real people to explore our desire with, we should get more creative. While the sex robots in development are targeted primarily at straight men, the wider range of products—including apps, digital content, and sex toys—are far more inclusive. Male sex toys are typically modeled on reality, while those aimed at women are much more diverse in creation. So maybe, Devlin wonders, the key to changing this market could be imagining sex robots as “embodied, interactive sex toys.” Perhaps women just don’t want sex bots.

But it’s tricky to open up discussions on diversity in a field that remains fairly taboo. Nevertheless, Devlin remains optimistic. “Diversity and equality is absolutely terrible in the tech world—not just in terms of representation in employment but also in terms of the technology itself. Let’s keep fighting to change that.”