Witnessing an eclipse is so overwhelming it has created a global community of “addicts”

Asking an eclipse chaser why they go to such great lengths to spend a minute or two beneath a darkened sky is like asking a person why they bothered to fall in love. Words, they stress, are mere approximations; it’s impossible to actually describe the feeling. But they try anyway:

Asking an eclipse chaser why they go to such great lengths to spend a minute or two beneath a darkened sky is like asking a person why they bothered to fall in love. Words, they stress, are mere approximations; it’s impossible to actually describe the feeling. But they try anyway:

I didn’t have a choice, it just happened.

You won’t get it until you see one.

Unlike anything else.

Gobsmacking.

It takes us to another place.

It really is a sort of high without ingesting anything.

I hear the words “overwhelming” more times than I can count from this group of people who proudly self-identify as addicts. In some cases, the confirmation comes even before I finish asking: “Oh, absolutely,” says Glenn Schneider, an astronomer at the University of Arizona, practically interrupting my question. “I warn people that eclipse chasing is addictive. It is. It’s an affliction as well as an addiction. I really am an addicted eclipse chaser. You see one, and it gets under your skin.”

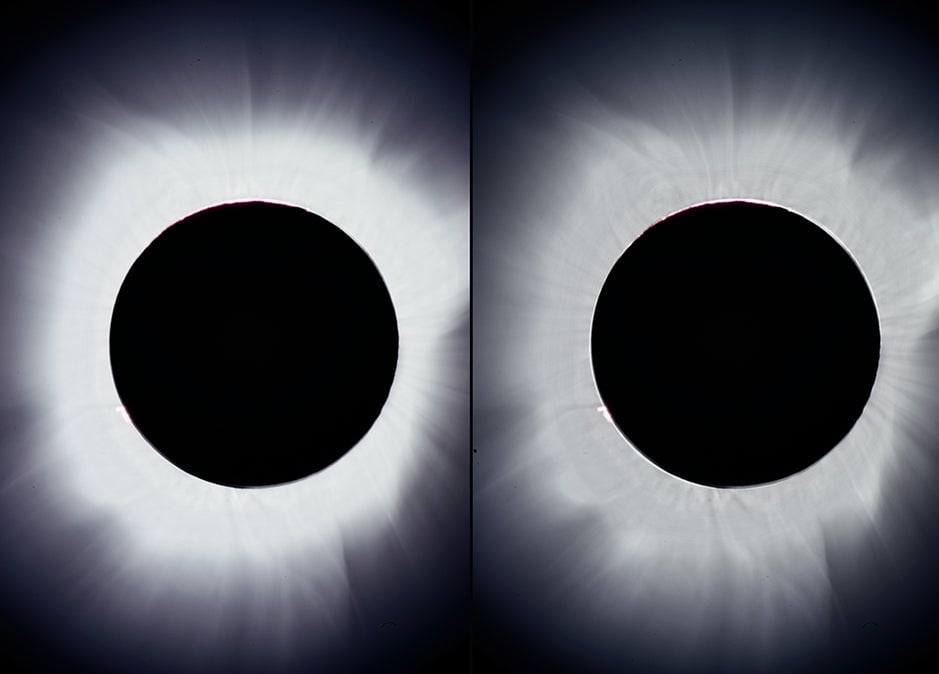

He calls the affliction “umbraphillia” and himself an “umbraphile,” a lover of the moon’s shadow (“umbra” is Latin for “shadow”). In grand, absorptive prose he logs on his website each of his moments under “totality,” the climax of eclipse viewing when the moon moves completely in front of the sun. Schneider has seen totality 30 times. The number of total minutes he’s spent in the moon’s shadow puts him nearly at the top of an international online leaderboard where hardcore eclipse chasers record their stats. “I remember all of them like it was yesterday,” says Schneider.

“You’re feeling celestial mechanics happen around you,” Schneider continues, his voice becoming full of an urgency I rarely hear in interviews, especially from scientists. He wants me to understand how phenomenal this is: “The moon’s shadow is stretching back a quarter of a million miles back up to its origin—it’s like a giant baseball bat with you at the end of it, being hit. It gives you a direct personal experience.”

It’s a lifestyle

The experience of a solar eclipse itself may be personal and even solitary. But the shadow addicts have formed a close-knit community of likeminded souls. It’s not competitive, because you can’t exactly stage a catch-up; you just have to wait for the solar system to line up again. Instead, they cheer each other on, discuss logistics, commiserate over cloud cover (what one chaser called “the c-word”) and plan trips over an email chain that Schneider estimes goes out to 1,000 people from all over the world.

They run into each other in remote regions, and eventually become friends. They’re a mishmash of professions: physicians and lawyers, a proofreader, a sculptor, a musician. Then there’s the reindeer farmer from Romania. “Yes, I’m serious,” says Schneider. “Catalin Beldea—he’s an excellent eclipse photographer.”

Eclipse chasers talk about the future of their lives with the absolute certainty of a devotee: “I know I will be chasing eclipses my entire life,” says Kate Russo, a clinical psychologist who has seen 10 total eclipses and has written three books on the phenomena. “The way it makes me feel is unlike any other experience I’ve really had. It’s become a part of who I am. It’s not an activity that I do or a hobby I engage in; it’s a way of life. It’s something I just feel absolutely compelled to do.”

Is missing an eclipse an option? “No. Absolutely not.”

Total solar eclipses happen roughly once every 16 months, and every eclipse in the next few hundred years has already been calculated out. All the eclipse chasers I spoke to said the only vacations they ever take are eclipse trips; many plan their expeditions several years in advance. Still, this is an expensive addiction—the trips frequently take eclipse chasers to opposite ends of the Earth. None of them knew, or wanted to say, exactly how much money they’ve spent.

“In total? I have no Earthly idea,” says Clint Werner, a San Francisco-based chaser who has 14 total eclipses under his belt. “We paid many thousands of dollars each for a cruise out of Darwin, Australia, to Borneo, Indonesia last year. My husband blanched when I told him the cost. But I said, ‘Next year it’s in America, so if you prorate it, it’s not as bad.’”

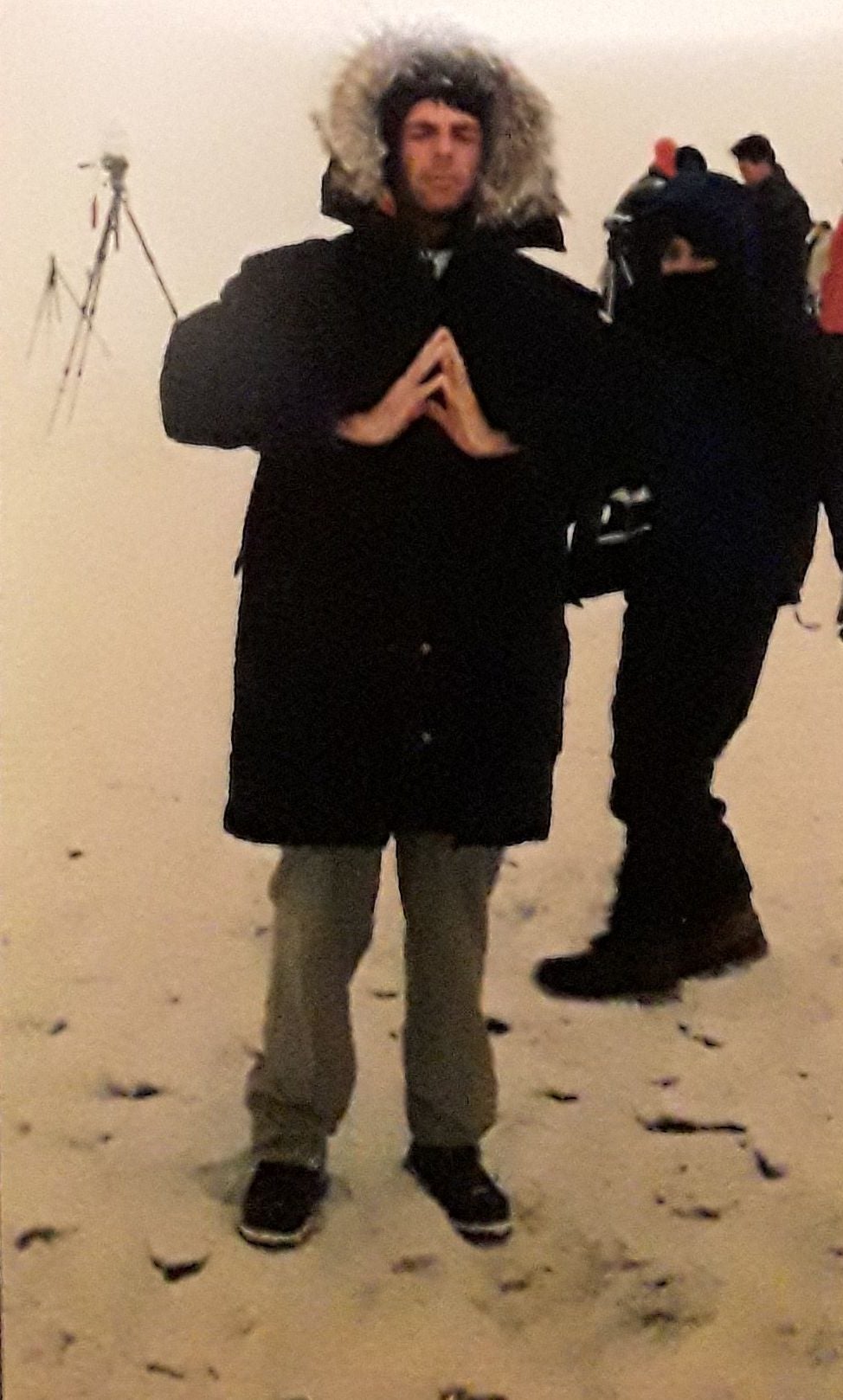

Werner and his husband have been to Zambia, Svalbard, the remote Alaskan Aleutian islands, and to the South Pacific (three times) to see eclipses. On their first date, Werner came out as an eclipse chaser: “He was trying to impress me by talking about having frequent flier miles,” Werner says. “I said okay, ‘let’s go to Chile for the next eclipse.’” They did.

“Donald screamed when we saw our first one,” Werner says. They’ve been married for 23 years.

A literally awesome experience

As a solar eclipse begins, the shadow comes swinging in. “If you have a view of the western horizon, an edge of deep indigo will appear towards the horizon. And it rushes up towards you. It’s like a wall moving—like a silent thunder storm. That’s the shadow of the moon,” Werner says. Then the light changes: “It’s unlike any light you’ve ever seen. Underneath trees there are these crescent patterns, like a pinhole camera of the sun. And the light has almost a metallic quality.”

And then totality itself, that black hole in the sky, with the sun’s aura of plasma emanating out in pearly wisps from behind it: “It’s so strange, and also a little threatening because it’s such an inversion of what you expect. You get a little scared. Your hair stands on end.”

Schneider, the astronomer, has been addicted since his first eclipse in a college football stadium in North Carolina in 1970. He was 14. “I had a well-rehearsed and practiced program of how I’d spend every second of totality,” alternating between cameras and telescopes and binoculars to get different views, he said. But at the critical moment, he was frozen. “I couldn’t do anything other than stand and stare at it. It was an overpowering and overwhelming experience. The binoculars stayed hanging around my neck.”

That is is what emotion researchers would call awe; Russo, the clinical psychologist, is especially interested in the emotional effect of eclipse-watching, and collects the experiences of other eclipse-viewers by way of long, extensive interviews. She’s come up with the acronym “SPACED” to describe the stages of emotion a person goes through as they watch totality: A Sense of wrongness, Primal fear, Awe, Connection, Euphoria, and the Desire to repeat the experience. Over and over, she says, this sequence holds true.

Other researchers have studied the effects of awe experiences and found that they can produce a sense of well being, and an altered experience of time: “Experiences of awe bring people into the present moment, and being in the present moment underlies awe’s capacity to adjust time perception, influence decisions, and make life feel more satisfying than it would otherwise,” a 2012 Stanford University study concluded.

In short, Russo says, it forces mindfulness, a mental state of being aware of the present that has been associated with health benefits in clinical studies time and time again. “You’re in a situation where you’re completely at one with the world, grounded, in that moment at that point in time. You have no concerns about your everyday life. You are so awestruck that you can’t avoid it.”

As a clinical psychologist, Russo has worked with people who are dying, and people who have just lost a loved one. Those patients, she says, “seem to understand how precious life is in that moment, that we really have to live the life that’s important to us.”

“During totality we can have those same feelings. I find that whenever I see an eclipse it gives me the life insights that I don’t normally get,” she says. “I feel that the world would be a better place if everyone could experience a total eclipse. You feel a part of something greater.”

Werner agrees: “It takes us outside ourselves and makes us think about the universal,” he says. “I believe [Carl] Jung said that if you don’t have the experience of awe in your life, you’re very susceptible to a number of pathologies.”

It’s true—Jung did say that. He wrote extensively on the idea of the “numinous,” a term brought into use by German philosopher Rudolf Otto to describe the ineffable feeling of fear and awe behind the experience of religion; Jung felt strongly that numinous experiences and their “peculiar alteration of consciousness” were vital to a healthy life. Jung would probably love eclipses.

Celestial Coincidences

“I think most eclipse chasers are pretty rational and understand the phenomenology as physics playing itself out on a celestial scale,” says Schneider. He is, too, for the most part. But then there are the coincidences.

For starters, the moon is 400 times closer to Earth than the sun. But the moon is also 400 times smaller than the sun, Schneider explains. That means that from Earth, the sun and the moon appear to be the exact same size. Without those exact proportions, total eclipses wouldn’t exist; either the moon wouldn’t appear large enough to blot out the whole sun, or it would appear too large, blotting out the sun’s halo of plasma called the corona, which is what makes a total eclipse so beautiful.

And actually, this is a unique period in history of the universe, the only era, in celestial time scales, when a total eclipse has been possible here on Earth. “The moon’s orbit is gradually moving outwards,” Schneider explains. “In the future—in a few hundred millions of years—we won’t have total eclipses any more.”

It’s also possible that in a few hundred millions of years, humans won’t exist either. “When you think of things on evolutionary time scales, it took us 4.5 billion years for us to get here,” he says. At that scale, a few million years in either direction is pocket change. “We’ve evolved as a species at the right time and right place in the solar system” to see this perfect alignment of moon and sun, says Schneider. “We’re pretty lucky.”

The big day

On August 21st, the day of the 2017 eclipse, Clint Werner will be in the high desert of eastern Oregon. “I’m hopeful that we will have perfect or good conditions. But there’s always the “c” word—I heard someone once say ‘eclipse chasers live in mortal dread of clouds that have not formed.’”

In the minutes leading up to the totality, Werner will wear an eye patch over one eye, like he always does, so at least one pupil is dilated and ready when the darkness of totality hits.

Kate Russo will be in Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming, surrounded by thousands of eclipse first-timers (the park is planning for the busiest day in its history). She’s excited for them all. “Maybe it opens a door they might never have opened,” she says.

Glenn Schneider will be in Madras, Oregon, just southwest of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. “I’ve had plans for that particular location for three years now. It was picked based on climate statistics over a number of years,” he says. “We play the odds like gamblers.”

This year’s eclipse will be the first in 99 years to cut a path all the way through the continental United States—tens of millions of people who may never have sought out an eclipse will see one practically from their backyards.

Every eclipse chaser has the story of their first eclipse, and that first inexplicable urge to see it again. The 1970 eclipse that got Schneider hooked as a teenager cut through much of the American Northeast; he says from what he can tell, much of his generation of hardcore eclipse chasers were “born” that day. “We may see that again,” he says. This year’s event could create a fresh wave of addicts, or reorient people to new life trajectories. Perhaps a child looking up at the sky on this fateful Monday will be aghast, and a seed of something will begin to grow. Perhaps they will become an astronomer.

In the middle of my conversation with Schneider, I mentioned I hadn’t made plans to see the eclipse. There was a pause.

“I need to stop the interview for a minute to say you can’t miss this,” Schneider says.

That was the message I got over and over: Just find a way to get to totality.

I booked a trip as soon as I got off the phone.