An 1868 article about the KKK captures the ethical paradox of talking about terrorism today

After troubling violence around a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia this weekend, photos of protestors wielding torches and making the Nazi salute quickly spread online. Reddit users shared a picture of a shirt reportedly worn in Charlottesville that quoted Hitler, and bystanders’ videos of a car attack on pedestrians were embedded by news organizations. But our ability to share such terrifying imagery creates a paradox: Sharing photos spreads awareness and helps defend against a social danger, and simultaneously also gives racist groups free publicity, fueling the fire.

After troubling violence around a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia this weekend, photos of protestors wielding torches and making the Nazi salute quickly spread online. Reddit users shared a picture of a shirt reportedly worn in Charlottesville that quoted Hitler, and bystanders’ videos of a car attack on pedestrians were embedded by news organizations. But our ability to share such terrifying imagery creates a paradox: Sharing photos spreads awareness and helps defend against a social danger, and simultaneously also gives racist groups free publicity, fueling the fire.

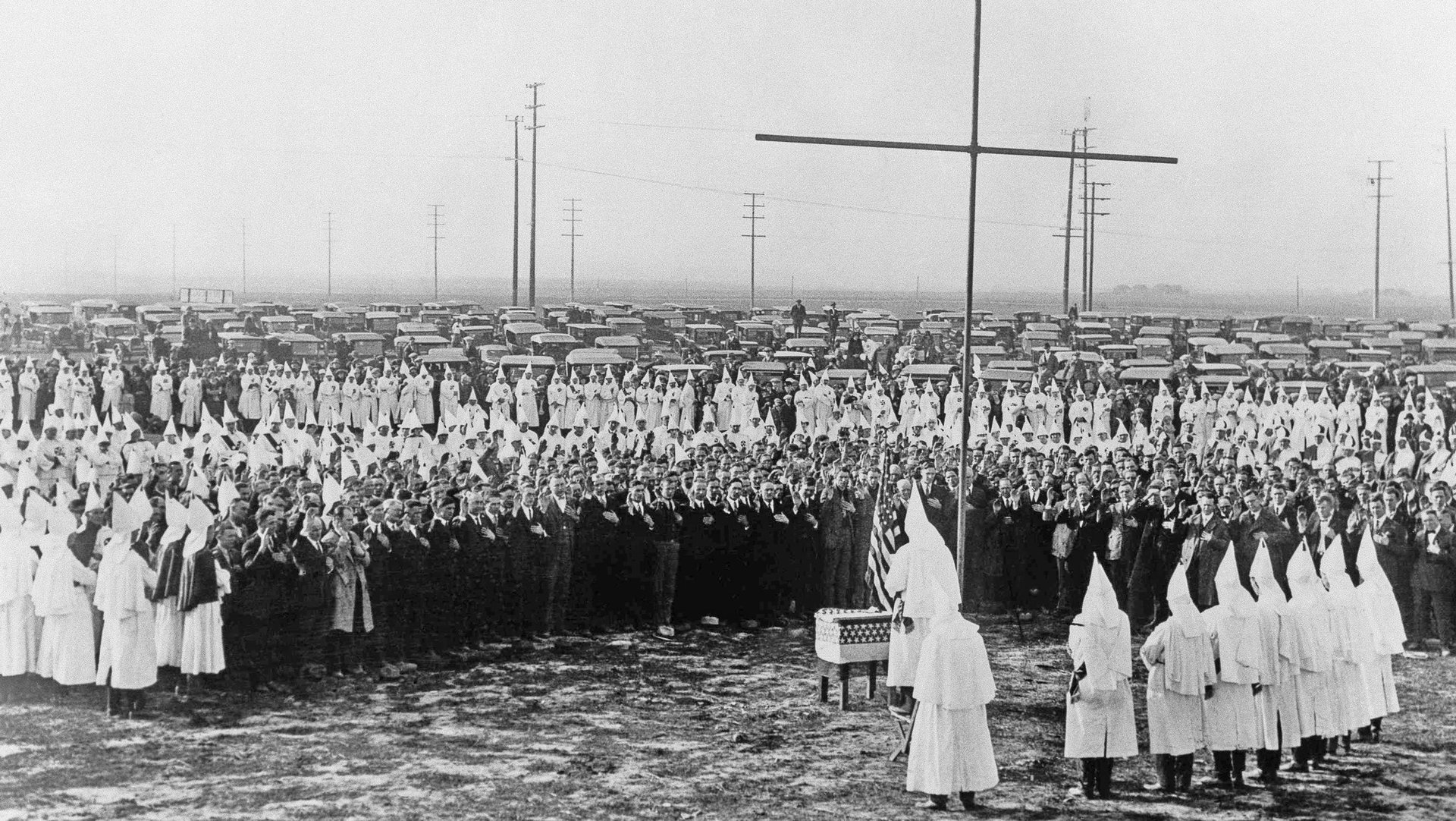

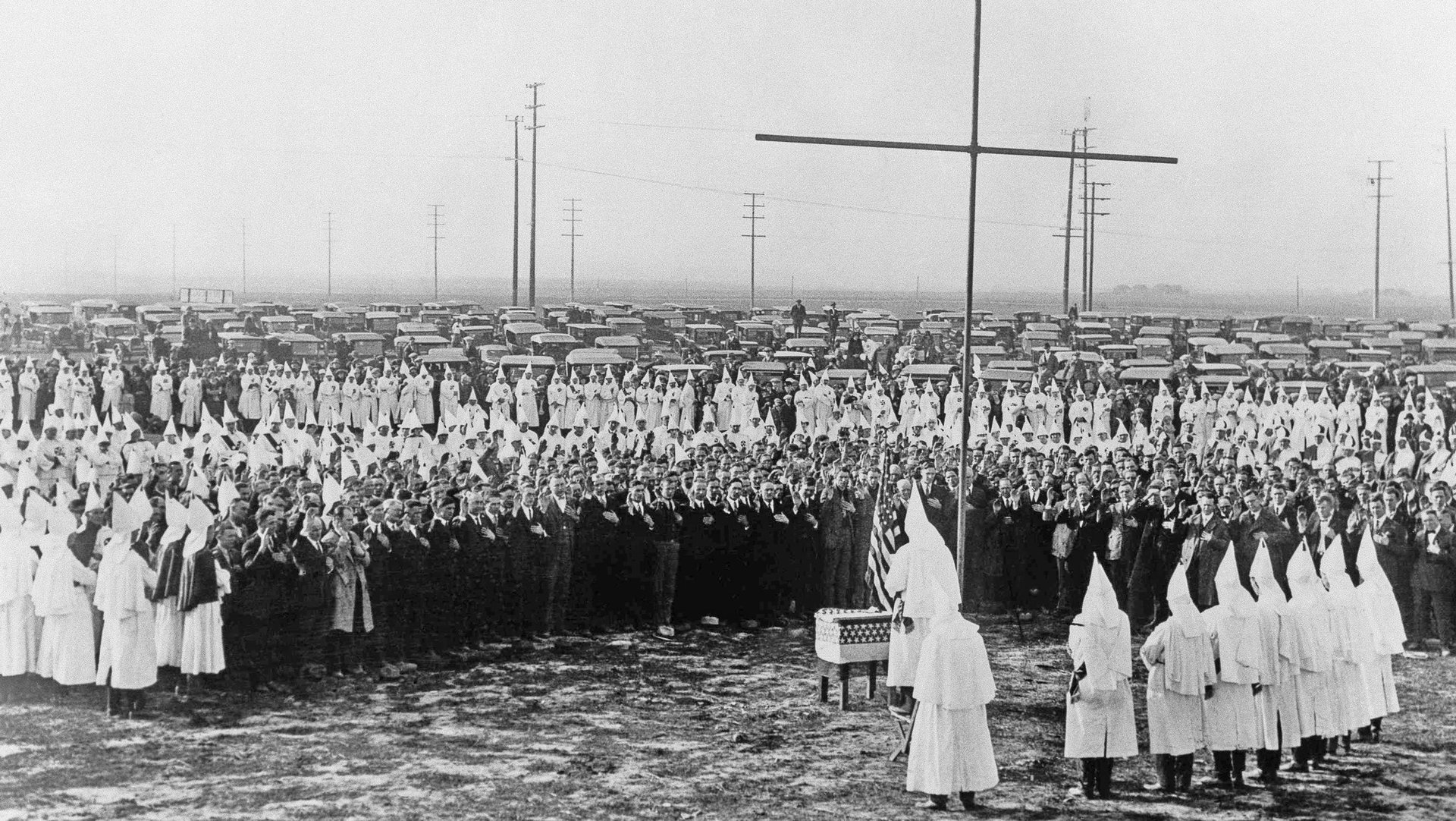

In March 1868 (pdf), a New York Times correspondent in Tennessee writing about the nascent Ku Klux Klan captured the same problem. When the very first KKK formed in Tennessee in 1868, its objective was to terrorize black Americans and prevent them from exercising their right to vote. Like today, people weren’t sure how seriously to take the fringe group: Was the KKK a military threat? Were they a political party? An outrageous hate group threatening progress? Or was it nothing more than bluster?

Controversial Tennessee governor William Gannaway Brownlow raised an early alarm about the newly formed KKK in his state, describing the group as an armed rebellion. The Times writer, “Omega,” responded sharply, calling Brownlow a demagogue and taking him to task for exaggerating the threat. It was precisely this alarmism, Omega wrote, that would give the Klan its power:

I have means of information quite reliable enough to warrant me in contradicting these alarming, sensational, political canards, even though indorsed (sic) by the terrified demagogues of the State, who are fit subjects for the ingenious, mysterious and wicked devices of the KuKlux Klan.

With racist condescension, the writer also blamed black Americans for spreading fear about the group that hated them. The supremacists’ “mysterious and horrible midnight demonstrations prove that its founders have a thorough and perfect knowledge of the negro character,” Omega wrote. “On the streets, in the fields and in their churches this mysterious organization and its midnight revelations are discussed by the blacks, and exaggerated accounts of its horrors repeated.”

What Omega forecast was, indeed, the power of the KKK’s spectacle of costumes and burning crosses to make headlines and spread whispers. But what he didn’t predict then at the group’s onset was the actual horror and death that the Klan would spread by the next year. It would inspire thousands of deaths by lynching by the turn of the century. By talking about terror, even if it carried misinformation or fear-mongering, people could prepare for a real danger.

In his plea for level-headedness, Omega underestimated the possibility that the Klan’s initial publicity stunts could empower and inspire far more horrific crimes. And his reaction to the rising terror illustrates the challenge that the US faces now as it tries to parse how big the growing white supremacist, or neo-Nazi, or alt-right movement is—or indeed what to call them—and what they’re really capable of.

The author dismissed the actual racism of the KKK and the hate they used, criticizing instead the justifiable fear of their targets.

Telling Americans, in essence, to “calm down” in the face of hostility of the highest order, lays the blame squarely at the feet of the wrong mob. In this tense national moment, do we remain measured, and wait for something truly catastrophic to happen, or risk action with all the rage and fear that it requires?