Google has some complicated lessons to learn from the James Damore case

The so-called “anti-diversity” memo leaked from Google this week has tech commentators (and beyond) in an uproar. One view is Google’s reaction puts it in a no-win situation. Another, more hopeful, is the commotion will force the company to reexamine its ideas and practices.

The so-called “anti-diversity” memo leaked from Google this week has tech commentators (and beyond) in an uproar. One view is Google’s reaction puts it in a no-win situation. Another, more hopeful, is the commotion will force the company to reexamine its ideas and practices.

When software engineer James Damore’s ten page objection to Google’s diversity initiatives became public on Aug. 7, I was struck by an impish thought: A ten page essay? You’re fired—for logorrhea. Also I hope you comment your code with as much detail! (Believe or not, the naughty spark predated the Aug. 8 firing.)

I then considered writing a lampoon of the situation: Perhaps we heard but one side of what was meant to be a Socratic argument. What if, in the spirit of an attorney who is able to defend either side of an issue, Damore had penned a second thesis that argued the opposing position?

In this fantasy alternative essay, Damore puts forth a blessedly simple thesis: Google products are made for people and by people. Among other skills, females have a gift for empathy and cooperation, thus a higher proportion of women at Google would help the company empathize with their customers, which would lead to better designs. Internally, life at Google would become both more productive and pleasant. Damore then reminds readers of the many female heroes in math and computer science. One can think of Emily Noether, author of a beautiful, deep theorem, seen by Einstein and other luminaries “as the most important woman in the history of mathematics.” Or the recently deceased Maryam Mirzakhani, Stanford mathematics professor, “the first and to-date only female winner of the Fields Medal.” In computer science, we have many heroes such as rear admiral Grace Hopper—the inventor of COBOL—or the women at Nasa’s Langley computer pool. Damore reinforces his point by citing studies that incontrovertibly establish an absence of gender difference in those fields. The conclusion would be inescapable: For Google, an affirmative action drive to hire more women would be enlightened selfishness. Do well by doing good.

Continuing the conceit, Damore sends the essays to a high-level Google executive who, misunderstanding Damore’s dialectical intentions, forwards the first of the two versions for publication on the company’s bulletin board.

But as I was amusing myself with the juicy made-up details that would embroider the tale, news of the actual essay spread. The real world took a humorless turn: Tempers flared, the mediasphere exploded, and Damore was fired. According to CEO Sundar Pichai’s Aug. 8 memo to the troops, Damore had violated the company’s code of conduct.

Out of curiosity, I looked up the company’s code of conduct. Interestingly, it concludes with [as always, edits and emphasis mine]:

And remember… don’t be evil, and if you see something that you think isn’t right—speak up!

Last updated August 7, 2017

Aug. 7, 2017…the day the media explosion started. Perhaps because I’m not a lawyer, I couldn’t put my finger on the specific articles that Pichai said Damore had violated. And yet, in view of the seriousness of the situation, I’m sure Pichai’s invocation of the code of conduct had been carefully vetted by company attorneys, by HR aka “people operations” experts, as well as staff in the recently hired diversity VP Danielle Brown’s organization.

Once fired, Damore easily found his way to the Wall Street Journal pages where he wrote a much shorter essay (presumably he had an editor this time) titled “Why I Was Fired by Google.” Denouncing his ex-employer’s “ideological echo chamber,” Damore poses in a provocateur’s Goolag t-shirt. (How that t-shirt advances Damore’s cause evades me. Unless what he really wants now is a money-making media persona. For that, he needs to pour code-words on the fire.)

From there, the fracas became more intense. We even saw the conservative David Brooks, author of the thoughtful The Road to Character, pen a New York Times opinion piece titled “Sundar Pichai Should Resign as Google’s CEO.” The normally even-keeled Brooks makes uncharacteristically strong accusations:

Pichai, the supposed grown-up in the room, could have wrestled with the tension between population-level research and individual experience. He could have stood up for the free flow of information. Instead he joined the mob. He fired Damore and wrote, “To suggest a group of our colleagues have traits that make them less biologically suited to that work is offensive and not OK.”

That is a blatantly dishonest characterization of the memo. Damore wrote nothing like that about his Google colleagues. Either Pichai is unprepared to understand the research (unlikely), is not capable of handling complex data flows (a bad trait in a CEO) or was simply too afraid to stand up to a mob.

Regardless which weakness applies, this episode suggests he should seek a nonleadership position. We are at a moment when mobs on the left and the right ignore evidence and destroy scapegoats. That’s when we need good leaders most.

Brooks’ op-ed serves as a measure of the trouble Google finds itself in, pointing to the company’s unresolved tensions over the roles, status, and pay of women in tech.

As the week continued, the controversy raged. Damore declared that he intended to sue his ex-employer, a Google company-wide meeting to discuss the firing was canceled (ostensibly because of online threats), more opinion pieces were published, polls were taken…

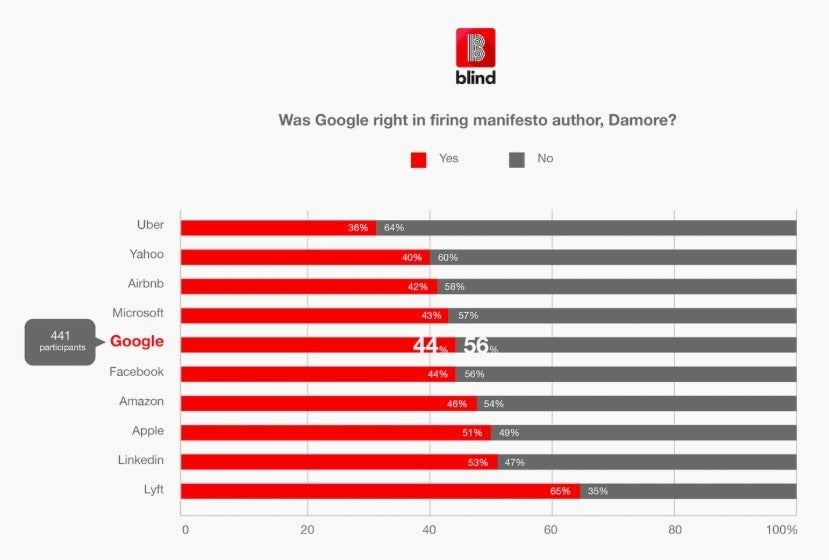

One such survey, run by Blind, an anonymous corporate chat app, canvassed more than 4,000 people in Valley companies and found that the decision to fire Damore wasn’t met with uniform approval… far from it (as reported by Business Insider):

At Google, 56% of those polled disapproved. At Uber, where CEO Travis Kalanick was recently deposed, negative sentiment reached 64%, but only 35% of Lyft employees disliked the decision to fire Damore. Apple employees were pretty much evenly split with 51% approving Google’s action. (We don’t know how scientific the poll actually is.)

As an eternal optimist, I hope the commotion will push Google’s management to take a calm and considered look at the reality beyond its established homiletic pronouncements of equality and opportunity, and its all-encompassing Don’t Be Evil goodness.