Forced to comply or shut down, Cambridge University Press’s China Quarterly removes 300 articles in China

Update: Cambridge University Press said in a statement on Aug. 21 that it was reinstating the 315 China Quarterly articles it had previously pulled from China “so as to uphold the principle of academic freedom on which the University’s work is founded.”

Update: Cambridge University Press said in a statement on Aug. 21 that it was reinstating the 315 China Quarterly articles it had previously pulled from China “so as to uphold the principle of academic freedom on which the University’s work is founded.”

China’s crackdown on academic freedom has reached the world’s oldest publishing house.

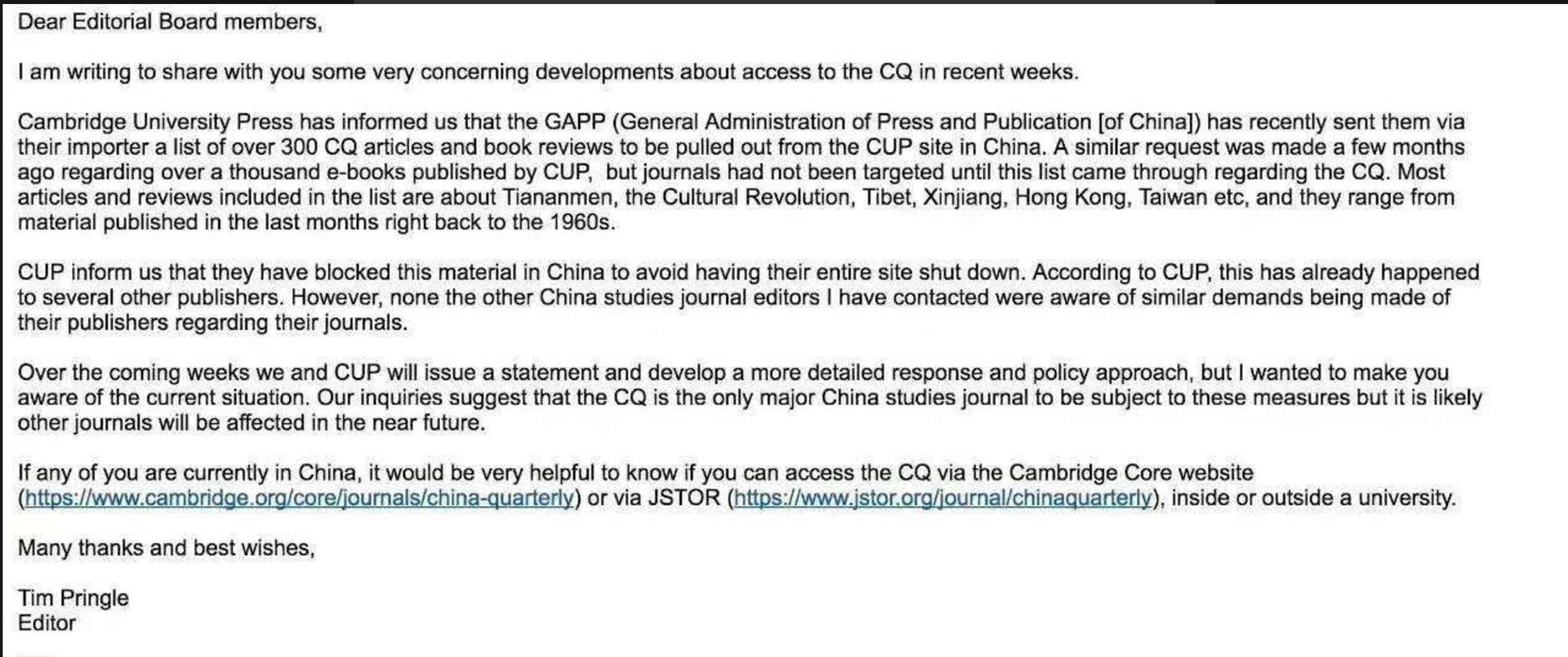

Cambridge University Press (CUP) said it has pulled over 300 articles and book reviews on its China site from the China Quarterly (CQ), one of the most prestigious journals in the China studies field, at the request of the government’s General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP). The news came to light after an undated screenshot of an email to CQ’s editorial board from the journal’s editor, Tim Pringle, went viral on social media today (Aug. 18).

According to Pringle, CUP complied with the request so as to prevent the shutdown of the entire CUP site. Most of the articles in question relate to topics deemed sensitive to the Chinese Communist Party, such as the Cultural Revolution, Tiananmen Square, Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, and date back to the 1960s, wrote Pringle, adding that CUP had received a similar request to take down more than a thousand e-books a few months earlier.

Yang Guobin, a sociology professor at the University of Pennsylvania who is also a CQ editorial board member, wrote on social networking site Weibo (link in Chinese) yesterday (Aug. 17) after he received Pringle’s email: “This is one of the most important international publications in contemporary Chinese studies, yet it’s subject to such restrictions… This is unheard of. Isn’t the Chinese government trying to promote contemporary Chinese studies?”

James Leibold, an associate professor at Australia’s La Trobe University whose research focuses on Xinjiang, called CUP’s decision “shameful” in a tweet.

CUP said in an emailed statement:

Freedom of thought and expression underpin what we as publishers believe in, yet Cambridge University Press and all international publishers face the challenge of censorship.

We can confirm that we received an instruction from a Chinese import agency to block individual articles from China Quarterly within China. We complied with this initial request to remove individual articles, to ensure that other academic and educational materials we publish remain available to researchers and educators in this market.

We are aware that other publishers have had entire collections of content blocked in China until they have enabled the import agencies to block access to individual articles. We do not, and will not, proactively censor our content and will only consider blocking individual items (when requested to do so) when the wider availability of content is at risk.

However we are troubled by the recent increase in requests of this nature, and have already planned meetings to discuss our position with the relevant agencies at the Beijing Book Fair next week.

We will not change the nature of our publishing to make content acceptable in China, and we remain committed to ensuring that access to a wide variety of publishing is possible for academics, researchers, students and teachers in this market.

China signed up to the International Publishers Association last year, and one of the body’s guiding principles is that of freedom to publish. The issue of censorship in China and other regions is not a short-term issue and therefore requires a longer-term approach. There are many things we can’t control but we will continue to take every opportunity to influence this agenda.

Rowan Pease, editorial manager of CQ, referred Quartz to a list of the articles blocked in China. China’s GAPP couldn’t be reached for comment.

A Chinese academic based in Hong Kong, who asked not to be named for fear of repercussions from speaking publicly, said the academic community was “totally shocked” by Pringle’s comments, and noted that there is a broad deterioration in academic freedom in China. What is more worrying, the academic added, is that the long arm of Beijing’s censorship apparatus is clearly extending beyond its own borders, citing the recent case of the detention of Feng Chongyi in China, a professor working at the University of Technology Sydney.