98% of murders in Mexico last year went unsolved

The capture of Mexican drug lord Miguel Angel Treviño Morales earlier this week has brought Mexico’s crime scene into the limelight, but its criminal justice system is perhaps what most deserves scrutiny.

The capture of Mexican drug lord Miguel Angel Treviño Morales earlier this week has brought Mexico’s crime scene into the limelight, but its criminal justice system is perhaps what most deserves scrutiny.

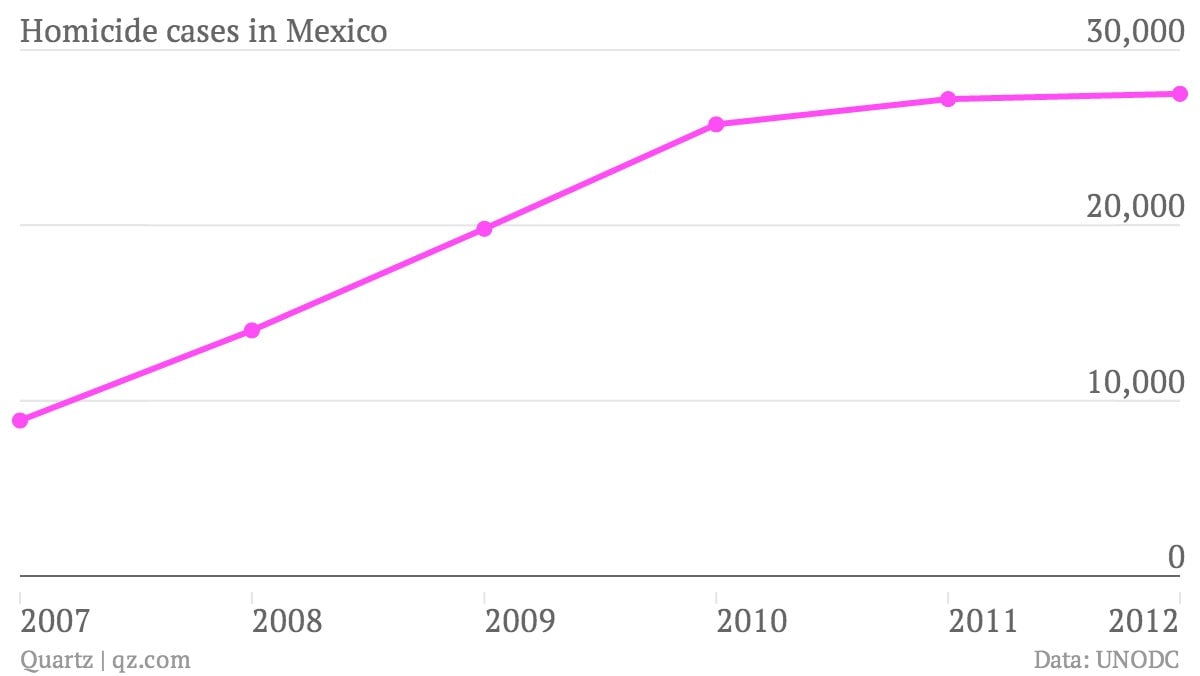

Some 27,500 people were murdered in Mexico last year. That’s more than Colombia and Venezuela—combined. It’s more than twice the number of murders in China, and nearly twice the number in the US. In fact, it’s more than every other country in the world save for Brazil and India.

But the most alarming fact about the homicides that occurred in Mexico last year is that a paltry 523 have resulted in a sentence, according to a new report from Mexico’s central statistics bureau (INEGI). That means 98% of the 27,500 murders in Mexico last year went unsolved.

In two Mexican states, Hidalgo and Tlaxcala, not a single homicide case resulted in a sentence, and in some of the country’s most violent states, the numbers are only marginally better. In San Luis Potosi, 99.6% of homicide cases have not been resolved; in Sinalao, 99.2%; in Chihuahua, 98.3%. Even in the state with the highest rate of sentencing, Mexico’s Federal District, 81.4% of murders still remained unsolved.

There are many reasons for Mexico’s inability to hold its criminals accountable. Local police are famously negligent when it comes to identifying, pursuing, and reporting crimes. A study in 2011 (link in Spanish) found that Mexican police investigated a mere 4.5% of crimes. Even when detained, criminals are rarely convicted. Only 31% of those arrested on drug charges between 2006 and 2011 were actually convicted, according to a report (link in Spanish) released by Mexico’s Attorney General’s office last year.

In 2008, Mexico’s National Rights Commission put the impunity rate at 99% (link in Spanish). Many of Mexico’s homicide cases are drug related—at least 60,000 are believed to have been killed between 2005 and 2011—but that doesn’t excuse the impotence of Mexico’s justice system.

The US has been trying to help Mexico on this problem for years. A series of reforms are meant to be implemented by the end of 2016, but as of last year, less than a quarter of Mexico’s states had even begun to implement them.