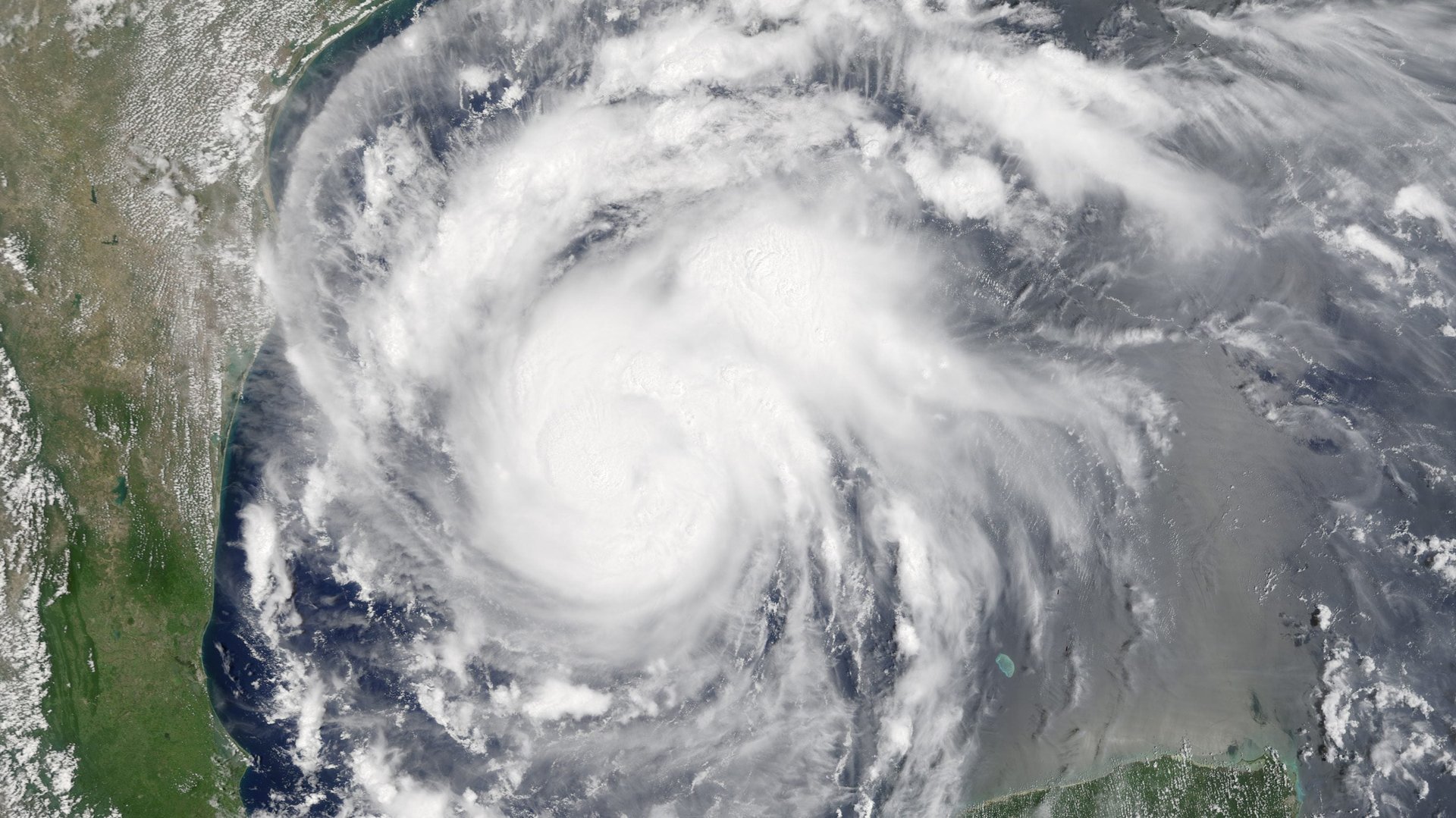

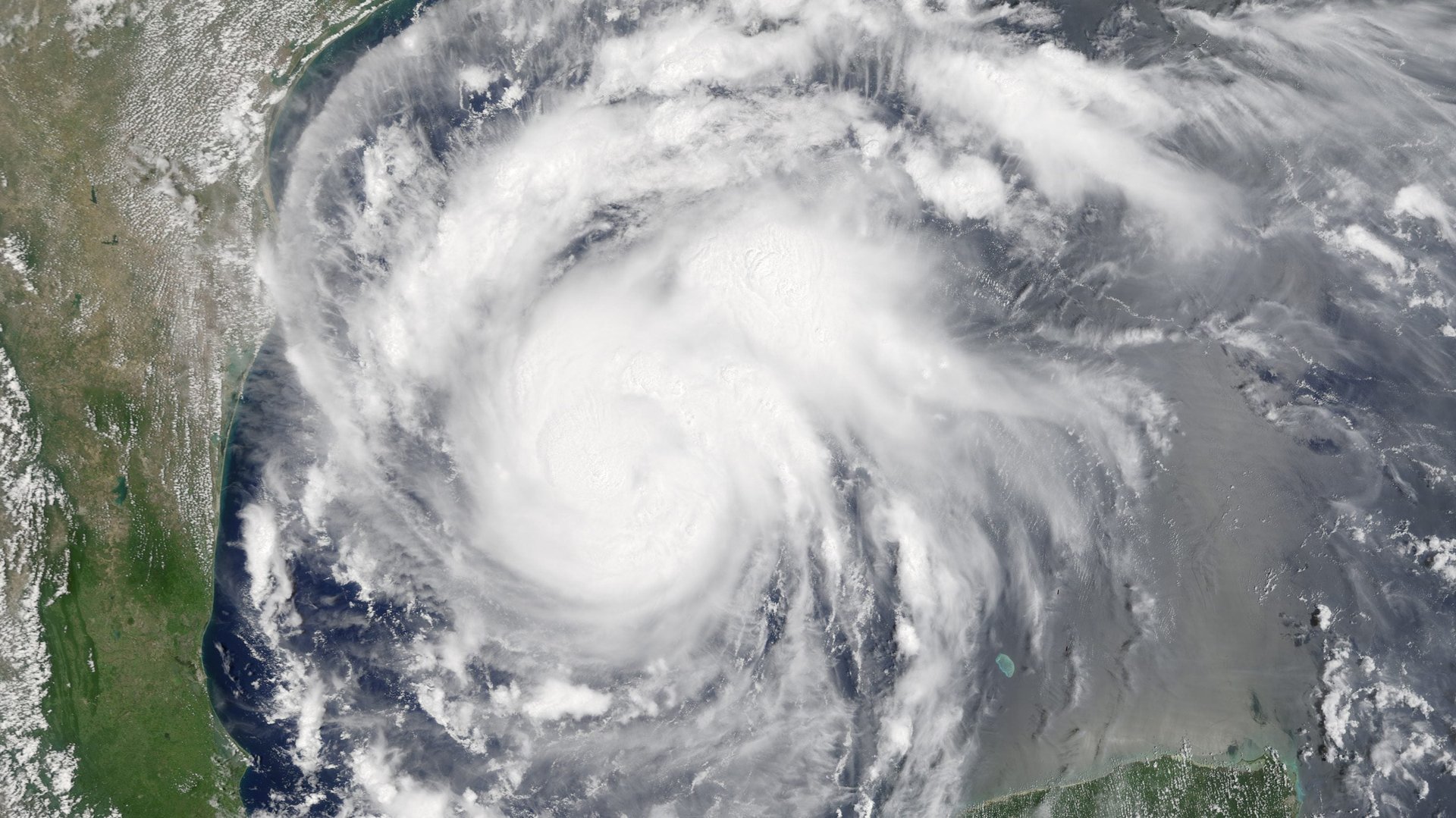

Hurricane Harvey developed so fast it took national forecasters by surprise

Hurricane Harvey intensified overnight, becoming a Category 2 storm as it gathered force over the Gulf of Mexico. The speed at which it developed shocked national forecasters.

Hurricane Harvey intensified overnight, becoming a Category 2 storm as it gathered force over the Gulf of Mexico. The speed at which it developed shocked national forecasters.

“It happened faster than expected. I was lead forecaster 24 hours ago. I didn’t know it’d be this fast,” Eric Blake, a hurricane specialist at the National Hurricane Center, said over the phone Thursday. Blake shares the rotating post of “lead forecaster” with 10 other hurricane experts at the Center’s Miami, Florida headquarters.

Storms in the Gulf are, by nature, fast-forming. “You don’t have the lead time, you can’t make predictions several days in advance,” says John Nielsen-Gammon, Texas’ state climatologist. “The Gulf of Mexico is so small that when something forms it’s only so long before it hits something.”

But the ingredients for a big storm were lined up; the waters of the Gulf of Mexico have been warmer than average this year, with bathtub-like temperatures breaking heat records all last winter. “That could be a contributing factor,” Blake says. “The hurricane extracts the energy from the ocean—there’s fuel there.”

There was also very little “wind shear,” says Nielsen-Gammon. “Shear” is a meteorological term for wind at different heights that are moving in different directions. “A hurricane extends all the way from sea surface to about 10 miles above the surface,” Nielsen-Gammon says. If the wind up top is blowing at a different direction from the bottom (i.e., there is more wind shear) it is hard for a storm to organize itself and develop into a cohesive, and therefore more destructive, formation. If the wind shear is low—meaning the direction of the wind is more uniform from top to bottom—a strong storm can coalesce much faster.

“But sometimes all these conditions [are there and still] don’t cause this to happen,” Blake says. There is no explanation yet for why the storm developed as fast as it did, he says.

For now, Blake and his colleagues will be watching the storm around the clock, and trying to get details about its severity out to the public.

“It’s busy, it’s exciting, it’s scary. It’s something like a newsroom when a big story is happening, I imagine,” Blake says. About 50 experts at the National Hurricane Center in Miami were tracking the hurricane when we spoke, collecting data and coordinating all the national offices that have a hand in storm tracking and response. It’s a fast-moving job. “We’re going to have aircraft in there continuously, and we’ll monitor temperature, wind, pressure. We’ll feed that into the models.”

Blake and his colleagues are also receiving data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s most advanced weather satellite ever built—the GOES-16 satellite, launched last year, can take far higher resolution images of the developing storm than any of its predecessors.

Hurricane prediction is a tricky business. But with more detailed information from the new satellite, Blake and other officials can more accurately warn the public about where, and how destructive, Hurricane Harvey will be.