How urbanization leads to obesity and malnourishment

Last week there was news of a rare victory—if you can call it that—in Americans’ decades-long battle against bulge: We’re no longer number one in obesity, it turns out, we’re number two. The dubious distinction of fattest country now goes to Mexico, where 32.8% of the population is obese, and where rates of obesity and overweight have tripled since 1980.

Last week there was news of a rare victory—if you can call it that—in Americans’ decades-long battle against bulge: We’re no longer number one in obesity, it turns out, we’re number two. The dubious distinction of fattest country now goes to Mexico, where 32.8% of the population is obese, and where rates of obesity and overweight have tripled since 1980.

But another thing happened in that same time period: Mexicans have been moving to cities. The urban population in Mexico increased by 36% between 1965 and 2000, and it is estimated that more than 82% of Mexicans will live in cities by the year 2030.

A new report from the Food and Agriculture Organization shows that the two trends might be connected.

There are many things that go wrong when you don’t eat the right kinds of food, but the one of the most serious problems is stunting—put simply, kids don’t grow like they should when they don’t eat enough. Another is micronutrient deficiency, or a lack of vitamins and minerals, which can lead to ailments like anemia or goiter.

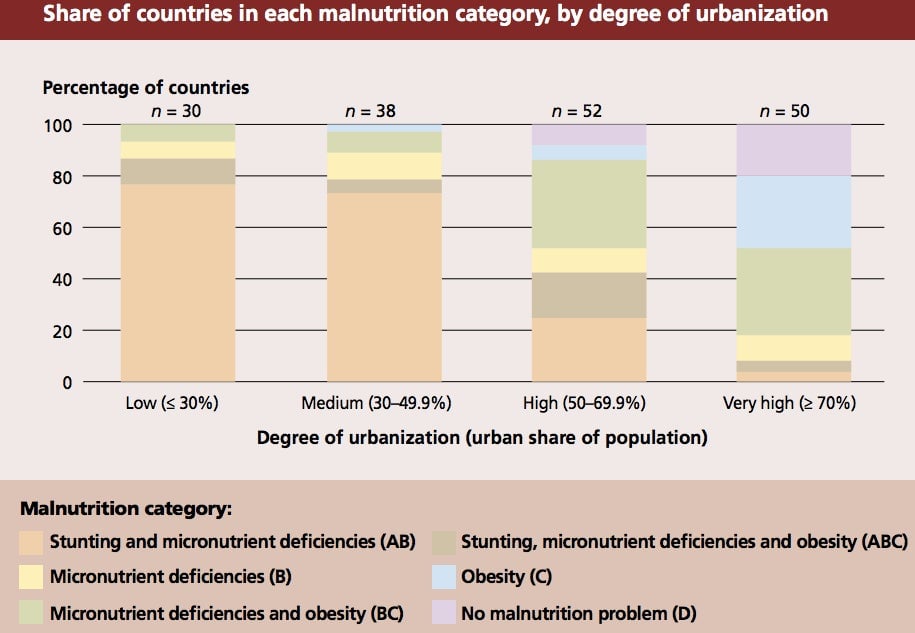

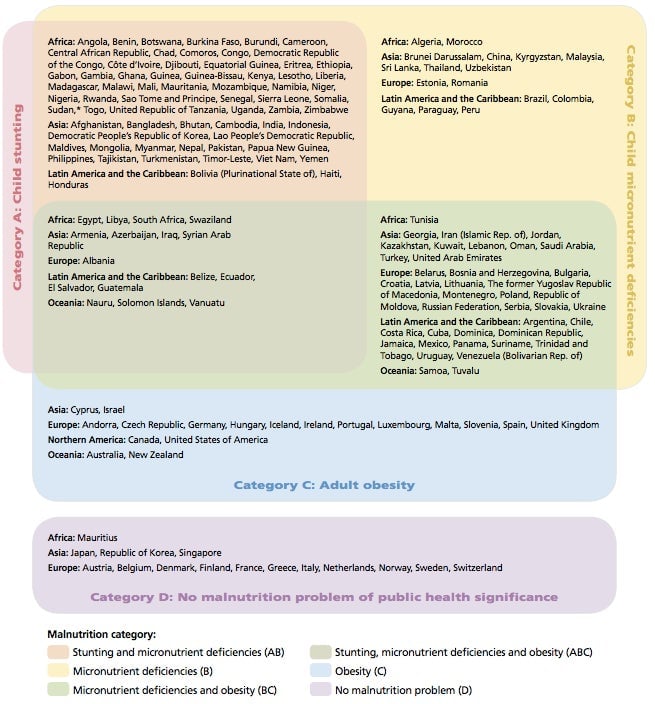

In any given country, as more people move to cities, the prevalence of stunting diminishes. Meanwhile, micronutrient deficiencies persist, even among obese people. Then, gradually, micronutrient deficiencies also decline, and you’re left with just very urbanized, very fat countries.

Here’s how it works: Urbanization leads to new, more sedentary types of jobs, as more people start slinging expense reports instead of hay bales. And as more women move into white-collar work, they have less time for cooking and rely more heavily on prepared food, which tends to be less healthy. Children, too, don’t play outdoors as much and spend more time sitting.

When we get richer, the report found, our diets get more diverse—but not necessarily healthier, which is why even people in rich countries often don’t take in enough vitamins.

“Evidence at the global level strongly suggests that rising household incomes lead to greater variety in the diet. At higher incomes, an increasing share of the household’s diet comes from animal products, vegetable oils and fruits and vegetables, that is, non-staples. Meat and dairy consumption increases strongly with income growth; fruit and vegetable consumption increases also but more slowly, and consumption of cereals and pulses declines.”

The most interesting part of this is that there are still a number of countries that have high levels of stunting, malnutrition, and obesity—all at the same time:

This can happen when there’s a high degree of income inequality, so there are both many rich (obese) people and many poor (malnourished) people, but also when a country gets rich incredibly fast, allowing households to buy food they never before were able to afford, according to Terri Raney, a senior economist at the FAO.

Sometimes, the problem is that the parents themselves are overweight, but they either aren’t able or don’t know how to feed their children the right kinds of food. Raney provides one possible example:

“When the child is weaning, in many places the most common weaning foods are not very nutritious, such as a rice gruel that consists of rice mixed with milk,” she said. “Unless that weaning food is supplemented with more diverse or more nutrient-rich foods, it can be a problem.”

The good news? Stunting and anemia have gone down across almost all the world’s regions. The problem most areas have now is too much of the wrong kind of food.