With tensions over North Korea mounting, China is testing antimissile systems of its own

In late July, US forces in the Pacific practiced shooting missiles out of the sky, with North Korea very much in mind. That’s not surprising, perhaps, given the tension between the two nations. But China, too, is looking nervously at the Korean Peninsula, and this week it tested antimissile systems of its own.

In late July, US forces in the Pacific practiced shooting missiles out of the sky, with North Korea very much in mind. That’s not surprising, perhaps, given the tension between the two nations. But China, too, is looking nervously at the Korean Peninsula, and this week it tested antimissile systems of its own.

In the small hours of yesterday morning (Sept. 5) local time, a unit of China’s air force shot down missiles from a “sudden attack” during a drill over waters near North Korea, according to a report from (link in Chinese) the Chinese military’s official news site.

The exercise simulated a real battle scenario, the report said, with soldiers being challenged to carry out orders while dealing with unexpected events, for instance needing to protect themselves from chemical weapons. The unit intercepted the low-flying missiles on its first attempt, the report said. It didn’t give details about the antimissile systems used in the drill, but noted they were displayed in a massive military parade recently overseen by president Xi Jinping.

The drill came two days after North Korea conducted its sixth and most powerful nuclear test. At the time of the blast, Xi was hosting an annual gathering of the leaders of BRICS nations, including Russia and India, in a southern Chinese city. The timing was not likely accidental on the part of North Korea. Pyongyang is unhappy with China for (among other things) implementing UN sanctions against it and has timed previous weapons tests to be awkward as well.

Beijing, predictably, issued a brief statement (link in Chinese) to “strongly condemn” the test.

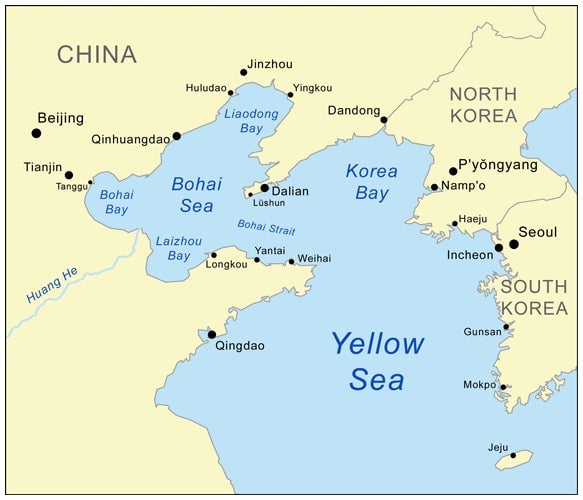

China’s antimissile drill occurred in Bohai Bay, southeast of Beijing and across from the Korean Peninsula. The bay has hosted several military drills recently, one after North Korea launched its second intercontinental ballistic missile in late July—from near its border with China.

Clearly China was practicing defending itself. But against which potential enemy? The answer is likely “whichever.” While most analysts believe the likelihood of conflict breaking out on the Korean Peninsula remains small, if it did occur, the nature of Beijing’s involvement would depend in part on how the fighting started.

An editorial last month in the Global Times, a nationalist Chinese tabloid that often reflects the thinking of the nation’s leadership, stated:

“China should also make clear that if North Korea launches missiles that threaten US soil first and the US retaliates, China will stay neutral. If the US and South Korea carry out strikes and try to overthrow the North Korean regime and change the political pattern of the Korean Peninsula, China will prevent them from doing so.”

China would “never allow chaos and war on the peninsula,” its UN ambassador, Liu Jieyi, said on Monday.

Earlier this year, China proposed a “double suspension” approach to defusing the tension on the Korean Peninsula. Under it, North Korea would suspend its nuclear and missile activities, and the US and South Korea would suspend large-scale military exercises. The US rejected that idea and proceeded with drills, while North Korea kept testing weapons.

In May, China announced that it’s developed a new type of missile interceptor capable of bringing down targets tens of kilometers above the ground flying 10 times faster than a bullet, saying the only other nations to have developed comparable technology were the US and Russia.

China is not alone in gearing up for possible conflict around the Korean Peninsula. South Korea, for its part, has conducted several military drills in recent days. It also agreed to the fuller deployment of the US’s Thaad antimissile defense system on its soil despite strong opposition from Beijing, which fears the powerful radars involved could be used against its own programs.