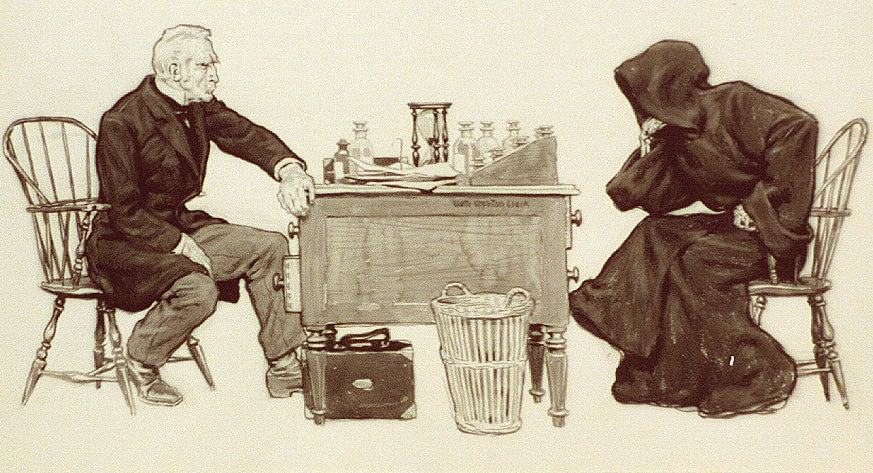

The first drugs designed to fight aging are ready for human testing

Earlier this week, doctors at the Mayo Clinic and the Scripps Research Institute published a review article in the Journal of American Geriatrics calling and outlining designs for human clinical trials on the first class of drugs developed specifically to treat aging.

Earlier this week, doctors at the Mayo Clinic and the Scripps Research Institute published a review article in the Journal of American Geriatrics calling and outlining designs for human clinical trials on the first class of drugs developed specifically to treat aging.

The “geroscience hypothesis” is relatively new to the world of accepted science. It states that targeting the fundamental mechanisms of aging can help treat or delay the onset of age-related diseases like type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, and various forms of cancers. The idea is to increase healthspan: the years in which people are viable, active members of society. The subtext though, is that these treatments also have the potential to delay aging itself.

Drugs like metformin and rapamycin have made headlines for their youth-giving potential, but were developed for other purposes, to treat diabetes and prevent surgical implant rejection respectively. Senolytics, developed at the Mayo Clinic, is the first class of drug developed from the ground up to delay or treat aging.

Senolytics target a known mechanism of aging, cell senescence. Normally, cells die a “complete” death known as apoptosis. Senescence is when a cell sort of zombifies: After senescence, the cell is essentially empty, and doesn’t replicate or do anything useful. What it does do, is hang around and secrete inflammatory chemicals which disrupt the functions of healthy cells adjacent to it. Why exactly some cells enter senescence instead of apoptosis is not fully understood, but one theory is that senescence is a defensive response that prevents a cell from becoming tumorous: it halts unchecked growth, stopping a cell from becoming cancer.

That said, concentrations of senescent cells can cause health problems, too. Even small accumulations of these cells are associated with failing heart health, osteoporosis, general run-of-the-mill frailty, and even cancer. The new senolytic drugs target a specific gene that once triggered, convince these undead interlopers to finally go quietly into that good night, to start apoptosis, the normal cell death. Most importantly, some of the senolytics tested have displayed an ability do this without harming otherwise healthy cells.

For example, in a study published in 2015 in the journal Aging Cell researchers irradiated mice legs to simulate the ravages of age. One application of a senolytic to the affected legs, and they showed a return to pre-radiation performance, a result that held up over the next seven months. The senolytics appeared to reverse the effects of aging.

The authors of the recent review argue that these drugs hold enough promise that human testing should be aggressively pursued. “If what can be achieved in preclinical aging animal models can be achieved in humans,” they write, “it may be feasible to alleviate dysfunction even in frail individuals with multiple [diseases], a group that until recently was felt to be beyond the point of treatment.”

But they also urge caution, knowing full well there’s a long way to go from animal models to humans. We don’t yet know whether or not there are side effects of senolytics in humans. There doesn’t seem to be a one-size-fits-all senolytic for every bodily cell type, so many drugs may need to be developed. And maybe most important, effectively testing a drug meant to extend already-long lifespans presents a unique logistical problem: to prove that drugs are preventing people from aging, enough time needs to pass to show that they haven’t.

But Kirkland and his team outline some options for overcoming those hurdles then finish by advocating immediate progress into human testing. “[Once] clinical trials are completed and the potential adverse effects of senolytic drugs are understood fully,” they write, “it is conceivable that the rapidly emerging repertoire of senolytic agents might transform medicine as we know it.”