A drug company schemed to push opioids designed to treat cancer on cancer-free patients

Even hardened cynics may wince over the findings of a new report from US senator Claire McCaskill outlining a drug company’s elaborate scheme to get paid for a cancer pain medication by faking disease diagnoses.

Even hardened cynics may wince over the findings of a new report from US senator Claire McCaskill outlining a drug company’s elaborate scheme to get paid for a cancer pain medication by faking disease diagnoses.

The Arizona-based pharmaceutical maker Insys Therapeutics allegedly falsified patient files, manipulated insurer approval processes, and bribed doctors into prescribing the opioid fentanyl to patients who didn’t need it, according to the Sept. 6 report titled “Fueling an Epidemic: Insys Therapeutics and the Systemic Manipulation of Prior Authorization.” McCaskill, who is a Democratic senator from Missouri, investigated Insys as part of a greater effort to understand the role that drug makers played in driving the current US opioid addiction crisis.

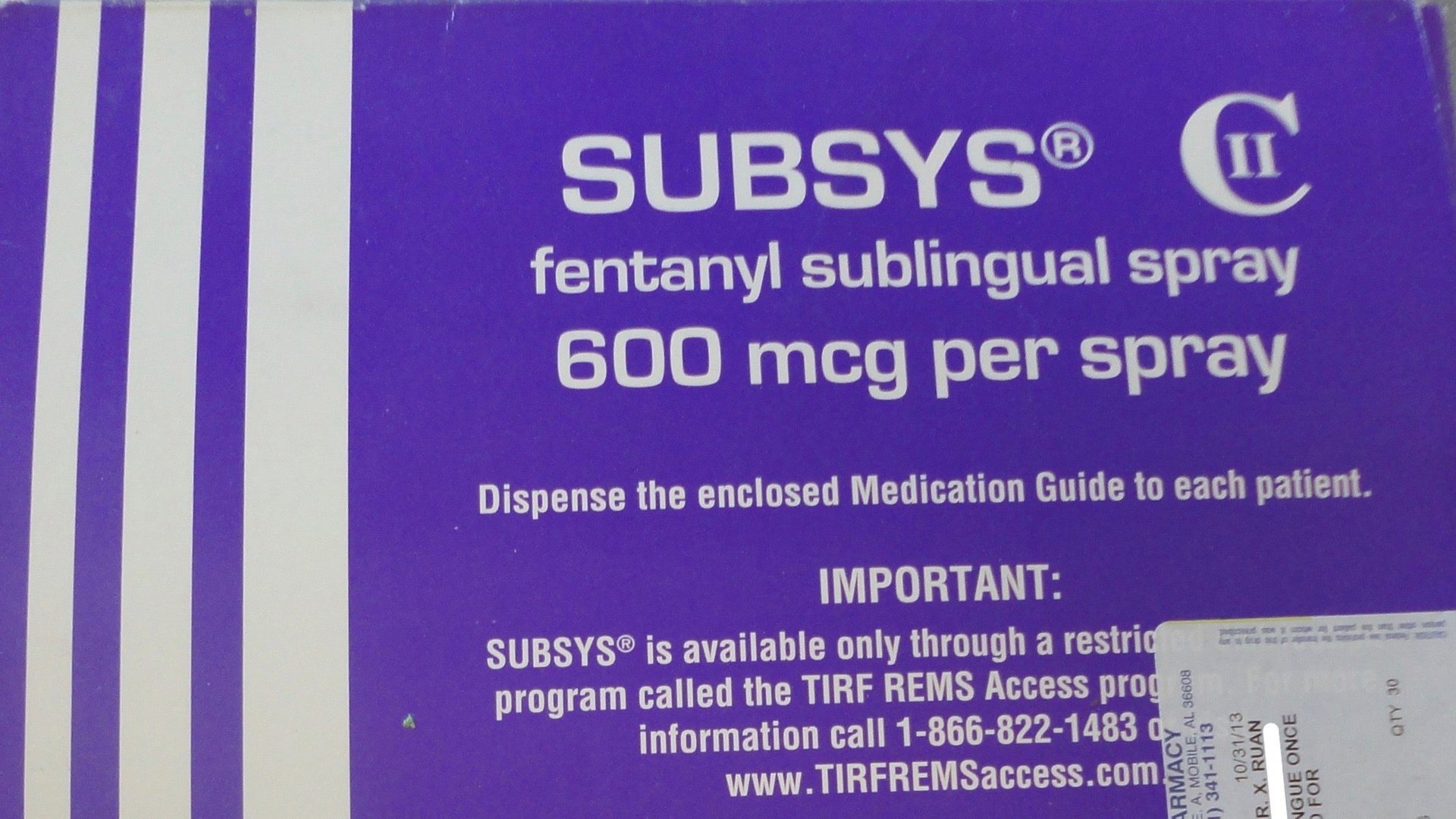

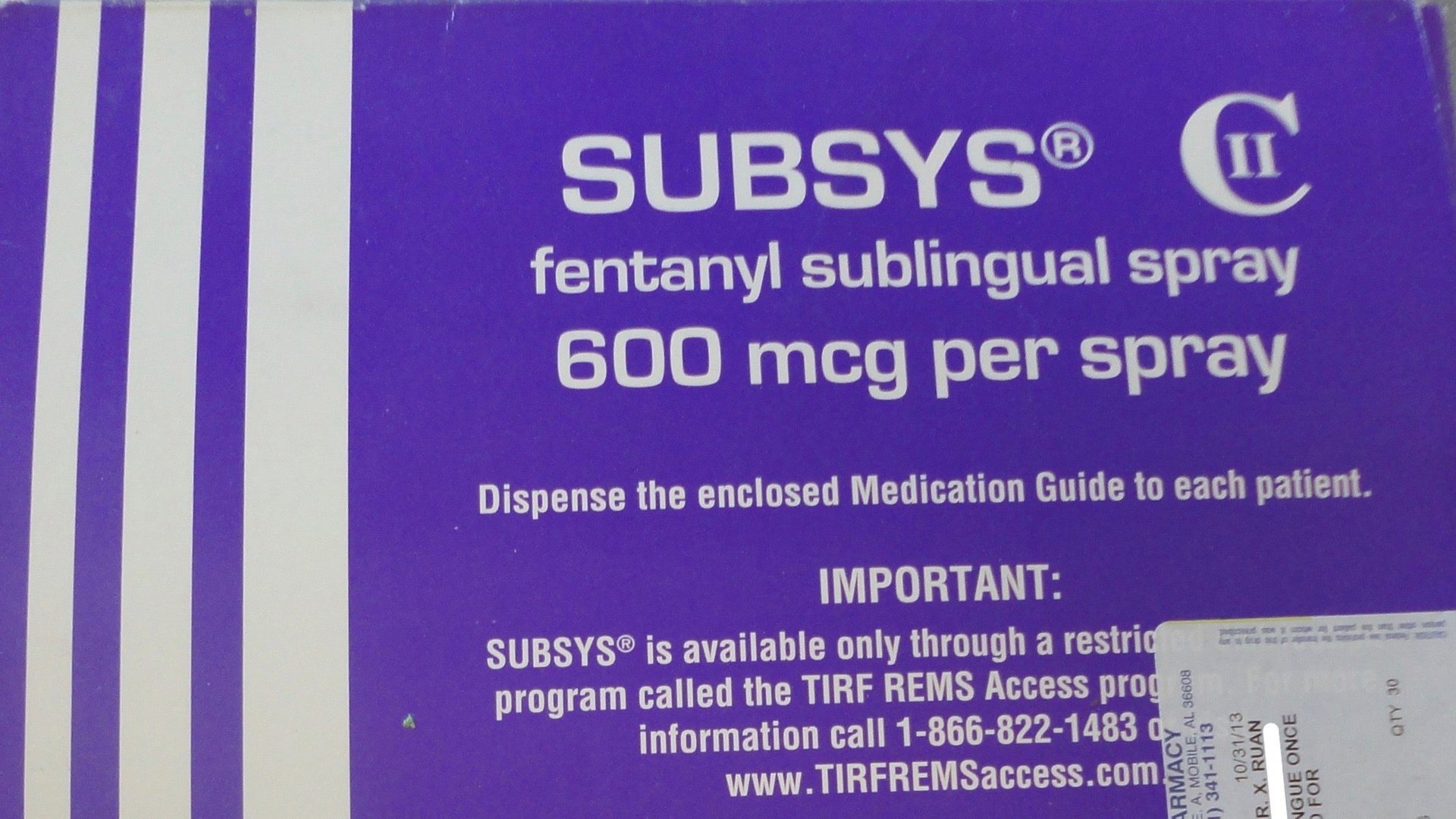

The report compiles information from civil and criminal lawsuits and investigations of Insys Therapeutics sales activities for the opioid fentanyl in a spray form, called Subsys. The drug was approved for cancer patients over 18 with acute, persistent pain by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2012. It’s an expensive medication that requires prior approval from insurance companies before doctors prescribe it.

“According to public reporting, lawsuits from Subsys patients, and criminal indictments, Insys Therapeutics has repeatedly employed aggressive and likely illegal techniques to boost prescriptions for its fentanyl product Subsys,” the report states. These activities seem to have begun around 2014, according to the report.

The “prior authorization” system in the US is a process by which doctors obtain insurance-company approval for expensive medication before prescribing it to a patient. The system is intended to ensure that alternative treatments are explored, if feasible; doctors’ offices traditionally call insurance companies to obtain the needed approval.

To get that approval for Subsys, doctors’ offices must confirm that the patient in question has an active cancer diagnosis, is being treated with an opioid (so is opioid tolerant), but that drug isn’t quelling ”breakthrough pain.” Breakthrough cancer pain is persistent pain resulting from cancer specifically which persists despite attempted treatment with other opioid medications. If any one of those factors is not present, authorization is denied and insurers won’t reimburse patients for the drug.

According to McCaskill’s report, Insys created a special internal unit tasked with contacting insurance companies directly in order to get prior authorization. Working with crooked doctors, drug company representatives allegedly led insurers to believe that patients did indeed have breakthrough cancer pain even when they didn’t have cancer. They avoided saying the word “cancer” while implying that was the diagnosis. Insys even used a phone number that blocked caller ID so insurers wouldn’t suspect the approval process was being manipulated by the drugmaker .

A recording of one such fraudulent call was provided by McCaskill’s office with the report. In the 2015 recording below, the Insys employee never reveals that she works for the pharmaceutical company, instead pretending to be calling the insurer from a doctor’s office.

On the call, the Insys employee refers repeatedly to “breakthrough pain” when asked about the patient’s diagnosis, avoiding use of the word “cancer.” The patient in question, Sarah Fuller, wasn’t diagnosed with cancer; she died in 2016 of a Subsys overdose.

In December 2016, federal prosecutors in Boston indicted former Insys executives on racketeering charges for a “nationwide conspiracy to bribe medical practitioners to unnecessarily prescribe a fentanyl-based pain medication and defraud healthcare insurers.” Those cases have not yet resolved. In a separate case in July 2016, Karen Hill, a former regional sales manager for the company, pled guilty to conspiring to pay illegal kickbacks to doctors in exchange for their prescribing Subsys.

Insys Therapeutics president and CEO Saeed Motahari submitted a letter to congressional investigators on Sept. 1 in response to the government investigation, which CNN obtained. In it, he reportedly wrote of McCaskill’s findings, “These mistakes and actions are not indicative of the people that are currently employed at Insys.”