In the 1980s, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe an American photographer, wanted to document the contributions of black female photographers in the United States. She dug through US Census reports and business directories to track down women like Jennie Louise Van Der Zee Welcome, who photographed the Harlem renaissance, or Elizabeth “Tex” Williams, the first black photographer in the Women’s Army Corp during World War II. Moutoussamy-Ashe finally published Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers in 1986, updating it in 1993. Since then there has been no other comprehensive compilation of the work of black women photographers.

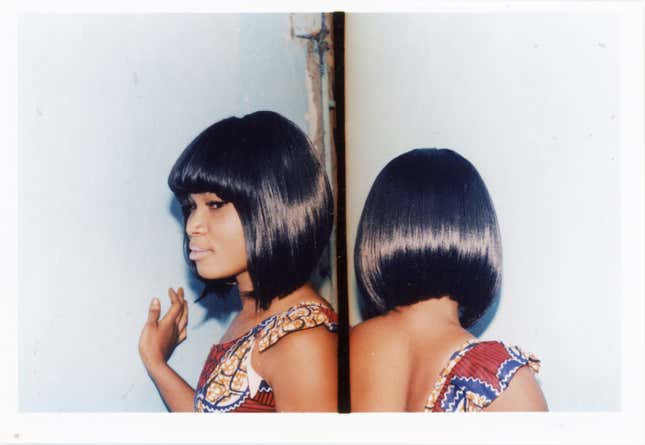

More than 30 years later, Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, a photographer based in Brooklyn, is publishing an anthology of work by black women photographers descent, Mfon: Women Photographers of the African Diaspora. Barrayn’s book, funded by a grant from the Brooklyn Arts Council as well as a crowdfunding campaign, features 100 female photographers of the African diaspora, including those based in the US, Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean. It’s named after Mmekutmfon ‘Mfon’ Essien, a young Nigerian-American photographer who passed away in 2001.

The book is the beginning of what will be an annual publication. Barrayn and her partners will also be offering a grant later this year to a woman photographer of African descent. Quartz spoke to Barrayn about Mfon, which will be available later this month.

Quartz: Why did you name the book after Mmekutmfon ‘Mfon’ Essien?

Laylah Amatullah Barrayn: I thought it would be really fitting to have it be in honor of Mfon, who was someone that I wanted to meet as an aspiring photographer back in the 1990s. I loved her sense of self and pride as a woman and as a Nigerian-American woman. She faced her illness, breast cancer, head on. She created art around her mastectomy and was a muse for many of the visual artists in New York City at the time. She died right before the opening of her seminal work, ”The Amazon’s New Clothes,” part of the “Committed to the Image” exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

How does Mfon diverge from Viewfinders, which you have described as an inspiration for the project?

LB: The major difference between that text and our book is that I wanted to do something international and make a real statement. That’s why I wanted to include 100 photographers. We also have a few essays from art critics, and the book is photo heavy. We have a range of genres represented from fine art and abstract to documentary and photojournalism.

How different is the world for black female photographers now compared to when that book was published?

LB: Black women photographers have more exposure than they did in 1986, but nothing compared to our counterparts, white women photographers, who have much more exposure and opportunity. Black women photographers are grossly underrepresented across the board, unfortunately. I’m doing my small part to add to this conversation by creating this document. But it is the gatekeepers, the editors, and curators, who really need to do examine their processes of inclusion.

What are the biggest challenges for female black photographers? What about for female African photographers, from the continent or in the diaspora? I deliberately tried to include African Americans and continental Africans in the book to really bring home the fact that this is a global black community. The challenges for us is that editors, curators, and gatekeepers are committed to only engaging with a select few that, I suppose, maintain their comfort level.

Can you tell us about how you chose the photos for the book?

There are several photographers in the book that I’ve admired for a while. I was on Instagram a lot. When I was in Africa, I tried to go to exhibitions and check out the scenes in cities like Cairo, Adis Ababa, Dakar, and Cape Town. I did tons of Google searches. I had tons of conversations on and offline.

What do you hope the book achieves?

I think it’s important to create a record. I would hate for another 30 plus years to go by and virtually nothing about the work that women photographers of African descent goes documented. I want aspiring photographers to be inspired by the work, effort, and sacrifice these women have made to become storytellers and photographers.