The island Bangladesh is thinking of putting refugees on is hardly an island at all

Since late August, Rohingya have been fleeing their homes in Myanmar and crossing into Bangladesh following a spate of sectarian violence targeting the Muslim minority. The latest round of military-led reprisals, which followed after an attack on Myanmar police posts by militant Rohingya, is among the worst the community has seen in years. Nearly 600,000 people have sought safety in Bangladesh, more than half of them children.

Since late August, Rohingya have been fleeing their homes in Myanmar and crossing into Bangladesh following a spate of sectarian violence targeting the Muslim minority. The latest round of military-led reprisals, which followed after an attack on Myanmar police posts by militant Rohingya, is among the worst the community has seen in years. Nearly 600,000 people have sought safety in Bangladesh, more than half of them children.

Each time the Rohingya flee Myanmar’s western Rakhine state—and there have been numerous such flights in recent years—Bangladesh, one of the world’s most congested countries, has to figure out how to best support them on its limited land.

There are temporary camps in the country’s southeasternmost areas, Nayapara and Kutupalong, set up in the 1990s and now housing about 30,000 registered residents, according to the UNHCR, the United Nations’s refugee agency. But these are longtime Bangladesh residents—the majority of them were born in the country or came as children. Newer arrivals have set up temporary shelters, and the situation is unsustainable.

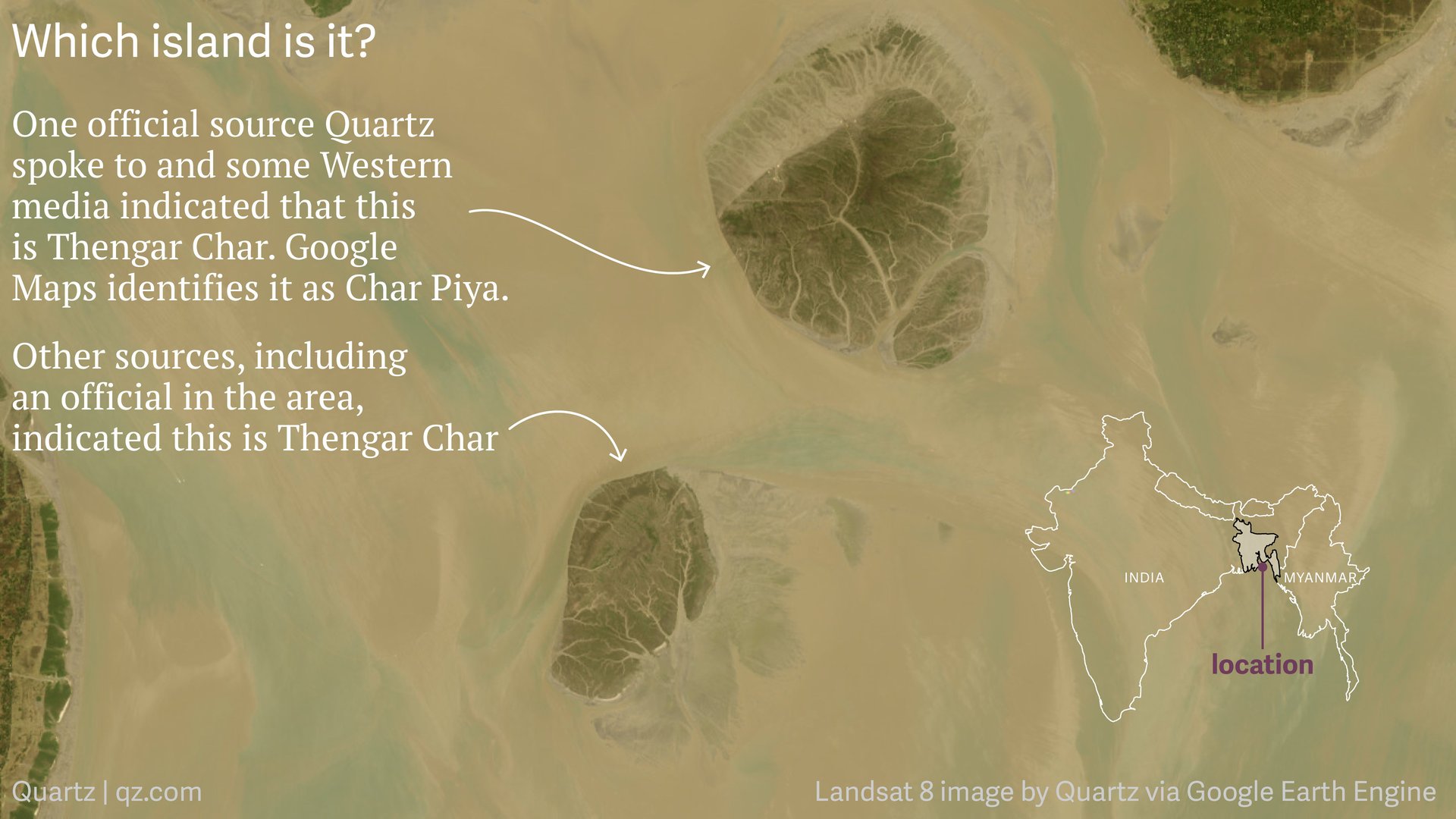

Plans to build a giant new camp have been announced, while one proposal floated publicly two years ago has surfaced again—resettle people on a brand-new island in the Bay of Bengal. In late September, the country said that if repatriation moved too slowly, it would take steps to move people there. Called Thengar Char, the island Bangladesh is considering using has appeared only recently as Himalayan sediments carried to the sea by the Meghna River collected and settled, forming a land mass. Bangladesh calls these newly surfaced land accretions char (pdf, p4)—and some of them are so new that even identifying them on a map can be difficult.

A geographer at a reputed Bangladesh university, a senior district official for the area in question, and a local media report point to the smaller island, to the left, being Thengar Char (Google Maps satellite imagery—a composite based on multiple years of images—doesn’t show it). Geographic coordinates provided by a source at the Navy point to the slightly bigger island to the right, but that is identified in online maps as Char Piya.

Geomorphologist Maminul Haque Sarker, of Dhaka’s Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services, also identified the island to the left as Thengar Char, and told Quartz that Char Piya is an older island. He explained that it can be difficult for any but locals to know which char is which since the newer accretions don’t show up on official maps for many years. It doesn’t help that changing water levels continually alter a char’s appearance when seen from above, and recent name changes add to the confusion. Char Piya is being rechristened Vashan Char, local officials said.

Satellite images show the rapid changes in size and shape in the years since Thengar Char first surfaced, as well as in its neighbor.

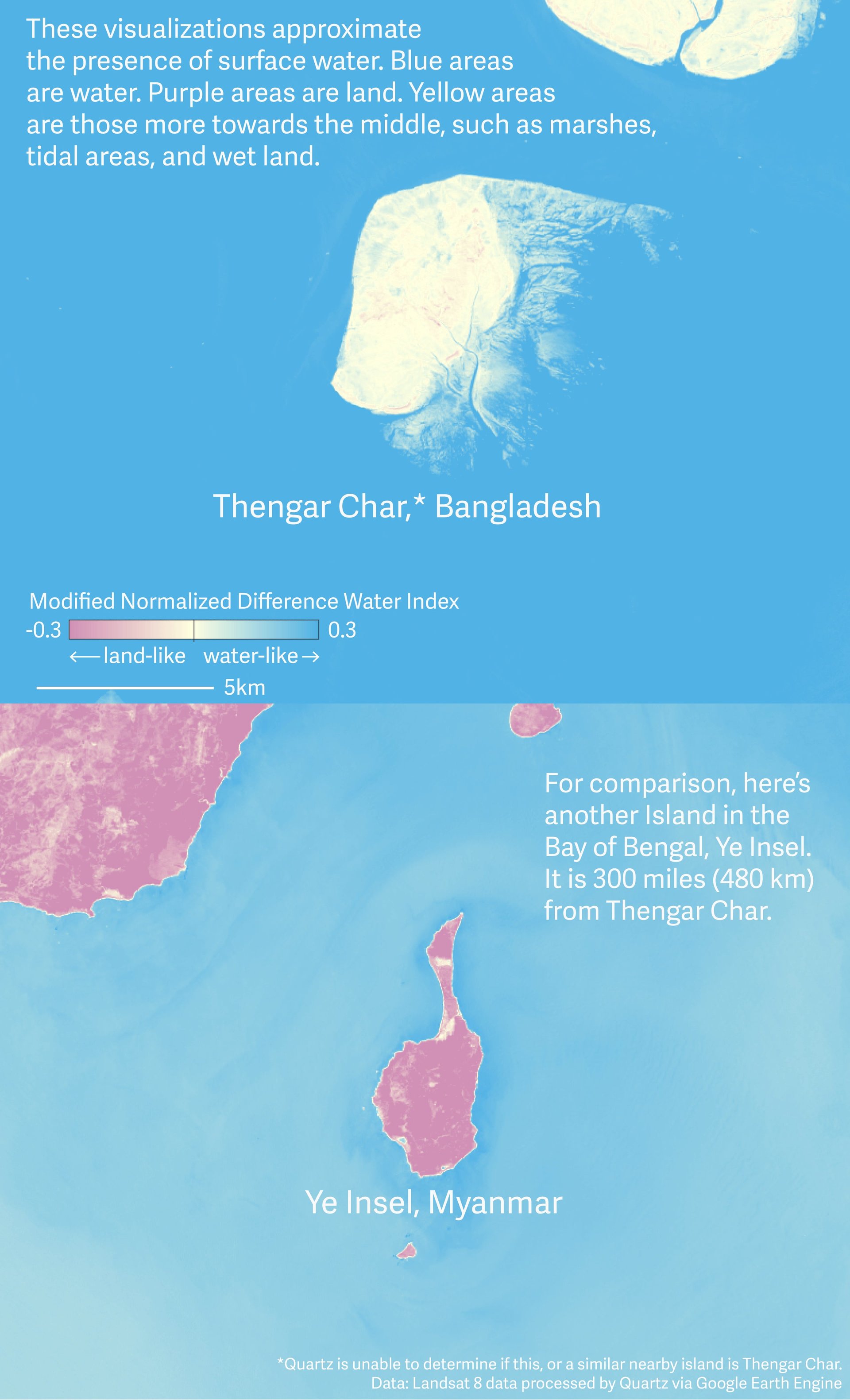

The young age of the low-lying island on the left, combined with the rainy and stormy seasonal conditions of the bay make it uninhabitable in the eyes of many. Much of the island is much wetter than islands that are typically habitable.

Compare the Bangladeshi island with Ye Insel, an island in Myanmar, using a measure known as the Modified Normalized Difference Water Index. Thengar Char, with index values near zero, reveals how wet the area is. Ye Insel, with index values less than zero, is solidly land.

Bangladesh’s ministries of foreign affairs, disaster management, and home affairs didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment from Quartz. In April, Sajeeb Wazed, the country’s information technology adviser (and also the prime minister’s son), wrote a defense (paywall) of the Thengar Char plan in The Diplomat, vowing conditions would be much better than those that refugees presently experience:

Some news reports have falsely claimed that Thengar Char is completely submerged for part of the year, a baseless allegation that subjected the government to unwarranted criticism. Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina dispatched a team of researchers to Thengar Char to closely examine its condition. The truth is that, as in any tidal region, waters rise and fall daily. As a result, a small percentage of Thengar Char—the coastline—is under water half of each day, at high tide, then exposed again at low tide. The vast majority of Thengar Char is never submerged.

The Bangladesh government will not build Rohingya settlement facilities in those areas of Thengar Char that are subject to tidal fluctuations. It is also doing its best to handle the influx of Rohingya people in the most humanitarian way.

The country could certainly take measures to re-enforce the island’s extent—currently around 20 square kilometres (8 square miles)—and build flood mitigation efforts. The Bangladesh Navy is supposed to be in charge of that, with a brief to build temporary housing for up to 70,000 Rohingya in the next two years, according to a report in the Dhaka Tribune. The Bangladesh Navy referred Quartz to Bangladesh media reports on navy responsibilities in the area. The decision to transfer refugees there or not ultimately rests with the government.

The plans for Thengar Char aren’t so different from measures Bangladesh has been taking on behalf of its own citizens. (A Reuters report quoted a village leader on a nearby island who said locals who have lost land to erosion should be given consideration for moving to Thengar Char ahead of the Rohingya.)

The country is currently in a seven-year joint project that began in 2011 with the Netherlands and the International Fund for Agricultural Development to improve life for people settling on five new char in the same district that Thengar Char is located in. The plan involves, among other components, building something called “polder embankments”—polder being the Dutch equivalent of char—to protect from storm surges. Bangladesh has been building these since the 1960s and 1970s, but recent research suggests that these earthen dikes may be making matters worse in the long-term by causing elevation loss since new silt can’t be deposited.

In the short-term, a report this year on the char development project noted that shifting tidal flows caused erosion (pdf, p8) that destroyed 8 km of newly built embankments in 2016, and that future shifts and erosion will be hard to predict or prevent.

As climate change threatens many parts of the country, Bangladesh has to make the most of the land it can recover from the water, whether on behalf of its own citizens, or those rejected by its neighbor. But making char suitable for anything beyond bare subsistence is easier said than done.

“No island is stable in the Meghna estuary,” said Sarker, the geomorphologist. “Erosion and accretion are very common phenomena.”