Lessons from a poor multi-ethnic school can heal a divided nation

Joe Lawrence started his first day of high school in east London with his head down the toilet. It was 1969 and the initiation ceremony— called “ducking”—frightened him. But he took comfort in knowing the same thing was going to happen to his entire freshman class.

Joe Lawrence started his first day of high school in east London with his head down the toilet. It was 1969 and the initiation ceremony— called “ducking”—frightened him. But he took comfort in knowing the same thing was going to happen to his entire freshman class.

And how bad could it be? Sure, it could be rough, but Barking was a town where everyone knew everyone else, including the milkman and the postman, a place where no one bothered to lock their doors (not that anyone had much to steal anyway). You lived among your people. One evening, Joe and his friends snuck to the pub. Their hearts stopped when they saw their economics teacher. He bought them all a beer, and offered some advice. “Drink them and then fuck off. I never want to see you in here again.”

Today, Barking looks nothing like the community Joe grew up in. Joe pauses after laughing about his encounter with the teacher. “It has changed as life changes.”

At his school, Barking Abbey, the proportion of ethnically white Brits has more than halved. The number of Bangladeshi students, who are now the largest ethnic group in the school, has increased five-fold. When it comes to winning academic awards, white kids are nowhere to be seen.

“To find a white British name like John Smith would be very, very difficult,” said Anthony Maloney, head of the 11th and 12th grades and a senior teacher at the school since 1995. The highest-achieving students in 2016, grades nine to twelve? Rokas Povilonis, Imran Haque, Tega Ayerume and Jeevan Fernando.

Barking Abbey is a microcosm of Barking itself, which has transformed since the 1990s from a predominately white community to a far more racially diverse one. Over the same period, this one-time bastion of working class Britain has become poorer, and life has become harder for its residents. Waiting lists for public housing (or council housing as it’s called in Britain) used to be six months long; now it takes 50 years. Entire families used to attend the school; now they can’t get in due to overcrowding. From 2010 to 2015, Barking and Dagenham jumped from the 20th poorest borough in the country to 9th: 30.2% of children in the borough live in poverty, compared to the average of 23.5% in London, and 30% in the UK (pdf). For two years in a row, Barking and Dagenham has been voted the least happy area in the country.

When the UK went to the polls to vote on whether to stay in the European Union (EU), Barking was resolute: 62% voted to leave. Margaret Hodge, the local member of parliament who campaigned for the country to stay in the EU, wasn’t surprised. “I couldn’t deliver what white people wanted, which was to turn the clock back to the white community I came into in 1994,” she said.

Just as the election of Donald Trump revealed America’s gaping inequality and deep pockets of despair, Brexit revealed an island of angry people whiplashed by rapid and far-reaching changes. For millions, being part of the EU had not delivered jobs. Or better wages. Or a higher standard of living. It only delivered more people.

Says Joe: “It wasn’t about people saying we don’t want foreigners anymore. I think it was about people saying we’ve got enough. Our community cannot support any more people coming in.”

I, Aamna Mohdin, was one of those people who came in. I was born in Somalia soon after the civil war erupted in the early 1990s. I travelled to the UK as a seven-year-old refugee. I was behind academically when I first attended Barking Abbey. I read To Kill a Mockingbird, and feared my teacher would know it was over my head. She quizzed me on it and gave me more: Pride and Prejudice, The Great Gatsby, Of Mice and Men, Emma, and Jane Eyre. I didn’t notice how the student body was changing, or the neighborhood; only that my teachers had exceedingly high expectations of me and that I should meet them.

Britain has opted to leave the EU, but the people (both newer migrants and more established immigrant communities) are still here, of course. And unlike before the vote, it is harder for politicians to ignore us. That means the UK faces the daunting task of rebuilding hundreds of deeply fractured communities, and finding solutions that bridge race, culture, religion and history.

That’s where Barking Abbey could have a role to play. It has faced down the one-two punch of austerity and changing demographics to continue producing top-performing students with a strong sense of community. I wonder, does my school offer clues that might benefit the rest of the country?

The way things used to be

When Hodge moved out of central London in the mid 1990s, the inner city she was leaving was diverse. Barking, on its eastern fringes, was not. “What hit you when you got out of the station at Barking was how white it was,” she said. “I’d never met so many great grandmothers who lived within ten minutes of their great grandchildren.”

Barking and Dagenham grew out of a wildly successful social experiment in the 1920s, an example of the modern welfare state created under prime minister David Lloyd George. At its core was the Becontree Estate, the largest single council housing estate ever constructed, according to Justin Gest, an assistant professor of public policy at George Mason University and author of The New Minority:White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality.

In the 1920s and 30s, the British government moved tens of thousands of families out of London’s congested inner city into new council homes in the outer London borough. These homes were a step up for many working-class families, boasting indoor plumbing, privet hedges and front and backyards. “We actually had a bathroom for the first time,” said Joe.

Ford Motors opened a large plant in Dagenham in 1931, providing dependable jobs and security. At its peak in the 1950s, Ford employed more than 50,000 people.

“It was easy to get a job,” recalls Joe. “You would go down to Ford’s, and you would do a tour of the factory and they go, ‘What do you wanna do’, and you go ‘I want to be an electrical engineer.’ ‘Okay, fine, here’s a three year apprenticeship, no problem. Start next Monday.’” He didn’t know anyone who went to university.

Pubs and churches were an integral part of the community. “We knew all the shop owners and they knew us, and our parents,” says Adam Moss, who attended Barking Abbey between 1975 and 1979. There were bowling leagues and billiards leagues; the Barking Power House electricity supply station supported a horticultural society, a staff magazine and a superannuation fund, according to Gest.

But starting in the mid 1970s, the once dependable jobs began to vanish from mainstays like the Power House and May & Baker’s, a chemical plant. By 2002, all but a small part of the Ford factory had closed. Ford Dagenham now employs less than 4,000 people.

Meanwhile, in 1980, the government introduced a program called “right to buy,” which gave long-term council housing tenants the opportunity to buy their homes at a huge discount. The supply of available public housing vanished, leaving the next generation with fewer and more expensive options. “If you go back to the 1970s, you’d be on the list for maybe six months and then there would be a house. And now there’s no point in even trying,” Joe says.

Come one, come all

Barking’s population explosion did not mirror London. It led it.

From 2001 to 2011, the borough’s population increased by 13% (pdf) and is expected to grow by another 10% (pdf) from 2015 to 2020. Barking and Dagenham is the epicenter of Britain’s most recent baby boom, with almost 50% growth in the number of kids aged 0 to 4 years old, between 2001 and 2011. Barking is home to the largest primary school in the country. It has built classrooms in parking lots to accommodate the growing student population.

From 2015 to 2020, the number of residents aged 10-14 is expected to increase by 30%, presenting a unique challenge for schools like Barking Abbey.

As Barking and Dagenham grew, its ethnic makeup changed dramatically. In 2001, black Africans made up 4.4% of the population, but by 2011 that figure jumped to 15.4%. The Bangladeshi population increased from 0.4% to 4.1% of the total population in the same period. The white British population, on the other hand, fell from 80.86% in 2001 to 49.46% in 2011.

The number of Muslims in the borough increased from 4.36% in 2001 to 13.73%. All other religious groups—except for Christian and Jewish—also increased. Mosques, Hindu temples, and gurdwaras were popping up throughout the borough as churches shuttered.

As a Black-African Muslim, I fit a couple of these categories. But at Barking Abbey my skin color or religion was always a strength, one that was understood and welcomed. I was never ostracized for it. When I was 12, my head of year and biology teacher, Maloney, selected me as one of a dozen or so “gifted and talented” students out of the whole grade. I was flustered, confused, and excited. (It involved a weekend away with my peers at a camp where I’d take part in a number of activities including abseiling and climbing). My mum was initially reluctant to let me go (“Why do you need to go sleep God knows where when you have a perfectly good bed here, at home?” she said), but she finally relented. It was during that trip that I realized that Maloney didn’t expect me to be good. He expected me to be the best.

Outside the school walls, not everyone was so welcoming to the influx of people. Residents complained about the new evangelical churches (they were “happy clappy churches”), and the smells from curries and other ethnic dishes wafting from kitchens along the high street. Clashes between the far-right and Muslim extremists spilled out into the streets. The accusation? We were not assimilating.

Political fallout

Starting at the turn of the century the far-right British Nationalist Party, with its message of returning immigrants to their home countries and preferential treatment for indigenous British citizens, started gaining traction. When in 2005, it won a staggering 12 council seats in Barking, Hodge realized she had to start having a more honest conversation about what was happening.

“No one was talking about immigration,” she said. “People were losing their jobs, they weren’t getting access to homes, their neighbors were changing, the children in the school were changing, the foods sold in the shops were changing,” she explains.

This created a huge issue for social cohesion in the borough. Desperate to have their frustrations heard, traditional Labour voters migrated to the BNP, which some viewed as racist and others saw as the only hope to stopping the tide of immigration. “The BNP was the only way to have a voice,” Lucy Iverson, a long-term resident in the borough told Gest, the author of The New Minority. “It had nothing to do with being racist. We were just bursting at the seams.”

And then, the global financial crisis rocked the world. Barking and Dagenham’s local government, which relies on national government funding, was told to halve its spending from £150 million to £80 million a year over the next five years. That meant less money for schools, hospitals, and the community—and more anger. (Barking Abbey’s long-awaited refurbishment plans were put on hold.)

“The number 1 issue for the people of this borough and the rest of the country is immigration. Mass, uncontrolled immigration,” says Peter Harris, leader in Barking and Dagenham of Britain’s other far-right nationalist party, UKIP. Like others, he insists the problem isn’t with the race of immigrants, but the numbers.

Gest has dubbed areas like Barking and Dagenham “post-traumatic” cities. Struck with deindustrialization and demographic change, these urban centers have responded by embracing far-right, nationalist leaders.

“They are consumed by loss—a loss of economic stability, a loss of political clout. They are consumed by a loss of social status,” said Gest, who listened to dozens of people explain their rage, and sometimes, their racism. “They feel they barely matter to the future of Britain and its power brokers.”

Barking Abbey

Amidst this tidal wave of change, Barking Abbey has remained a consistent safe haven.

On a cold and rainy Wednesday in March, students in one of Barking’s eighth-grade English classes are grappling with a narrative writing project. Humpty Dumpty, the main character in a well-known English nursery rhyme, is their starting point:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again

One group of boys decide Humpty Dumpty is a Mexican immigrant on the run. “Let’s call him Pablo” one boy shouts. Another sets the scene: “Let’s go into the future where Trump builds the wall and makes Mexico pay for it.” The students debate whether the character should be a called an immigrant, an asylum seeker, or a refugee.

They decide Pablo is an undocumented migrant suddenly faced with Trump’s border wall and present it to the class. When the teacher asks the genre of the narrative, one boy says it’s set in a dystopian future. The teacher corrects him; their narrative fits in today’s political landscape, perhaps with more detail and nuance than one might find in a US presidential debate, or a small island nation’s decision to leave the EU.

Barking Abbey should not be thriving. It has faced successive budget cuts. “We’ve got roofs that are leaking, we’ve got buildings that we’ve had to shut down because they are not safe for students or staff to be in,” said Jo Tupman, the acting head of school. Portable cabins that act as classrooms are scattered around the school yard. They were only meant to have the cabins for two years; they’ve been there for 15 years.

And yet Barking Abbey shines bright. Its students are among the best-performing in the borough, consistently outpacing the national average. In 2016, 63% of students achieved a pass in English and maths (two core subjects in the UK), compared with 60% in the borough and 59% in England overall.

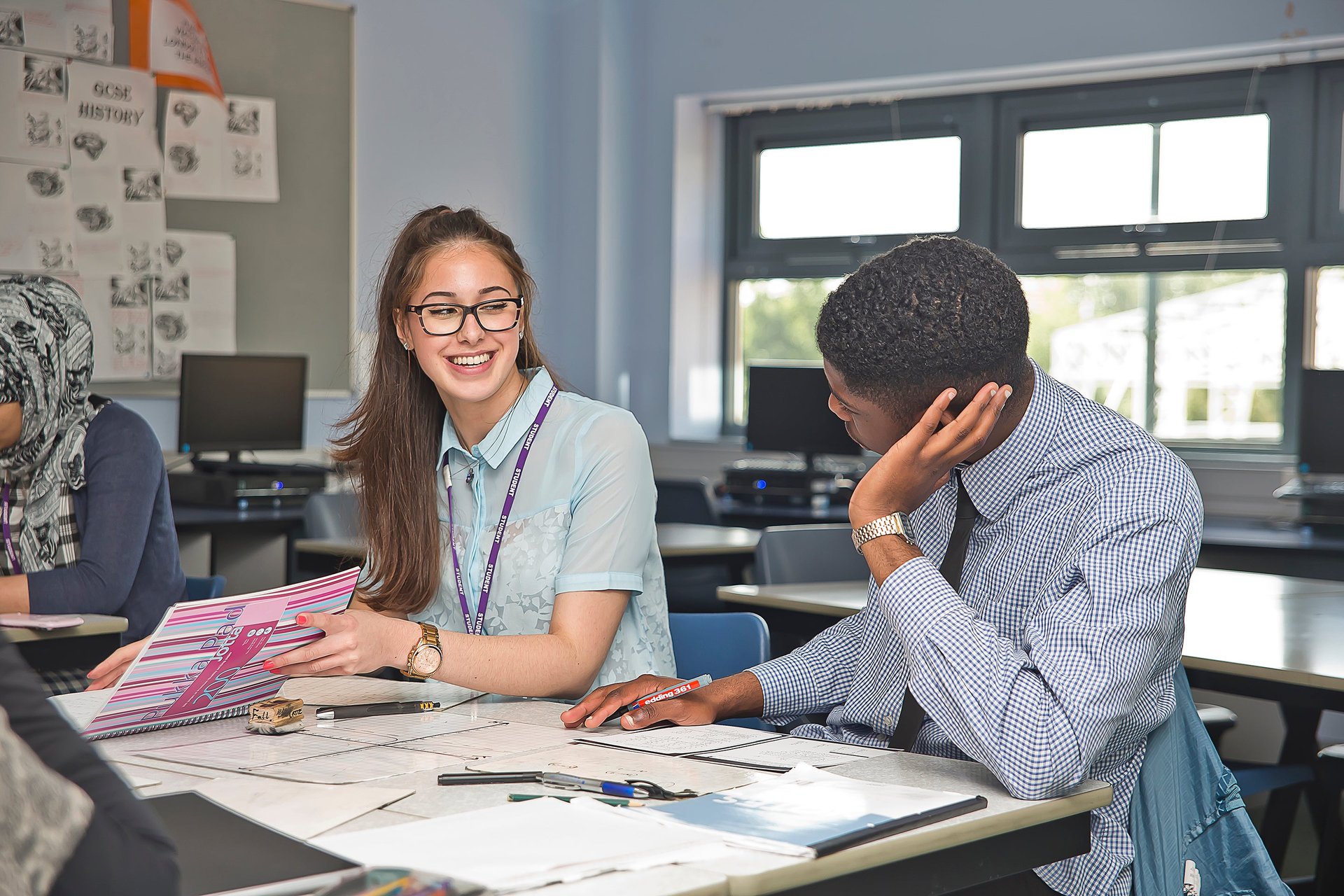

The cafeteria is a sea of students in black blazers and red and gold ties, where headscarves mingle freely with braids and buzz cuts. The only racist incident that any teacher could recall was a white family angry at all the immigrants. The family started yelling at the school receptionist using racist language. They were promptly removed from the school grounds.

If there is tension, it is from older, more established, immigrant families resentful of newer immigrants for taking up so many places. And then there’s the awkward fact that white working class British students are underperforming, and not just at Barking Abbey: 2015 research using UK census data showed only 13% of them go to university compared with 53% of the poorest Indian kids and 30% of the poorest black Caribbean kids.

“All of a sudden you have this influx of very determined and very focused [students],” Maloney, the head of pastoral care, explains. White British students were not only overwhelmed, but were quickly overtaken.

The students reflect that when they discuss their own experiences. Do parents put pressure on them? Speaking with students, one white 11th grader replies: “My parents will motivate me, but they understand my grades aren’t my worth.” Another student, whose parents were African migrants, immediately grumbles, “I wish my mum understood that.” She studies all the time, she said, and is constantly stressed out.

The students are uncomfortable talking about race (“Can I say black?” one white girl asks. Another bursts into laughter when he says “Asian” and “white”), but don’t pretend to be post-racial. They all agree that growing up in such a multicultural school is a huge asset to them. It makes them “more tolerant,” one student says. She goes on to explain why: “Every day we see the whole range. You get to know them,” adding that, “I don’t think we have those pre-judgements here…You just think that’s another student in this school.”

The secret sauce

The best schools create communities to insulate their students against braying social, political, and economic forces.

In recent years researchers have homed in on the importance of belonging in determining kids’ ability to stay in school and succeed there. Researchers from Stanford University conducted a one-time intervention in five diverse California middle schools to help teachers empathize with students. Suspension rates halved and kids reported feeling more connected at school, the study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed.

In a separate experiment, Geoffrey Cohen from Stanford and Julio Garcia, from the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropologia Social in Mexico asked a group of underachieving seventh graders at a suburban middle school in New England to write an essay describing a personal hero. Teachers corrected the essays with comments in the margin. Then the class was divided in two groups, with each group given the option to revise their papers. One group got a Post-it note that said: “I’m giving you these comments so that you’ll have feedback on your paper” and the other received a Post-it that said: “I’m giving you these comments because I have very high expectations and I know that you can reach them.”

White students, who did not face any threat of being stereotyped, performed slightly better in the “high expectations” group. But the gap between black students was huge: 17% of those who received the standard Post-it revised their work, compared with 72% of those in the “high expectations” group. Cohen told EdWeek, “The simple act of answering, ‘Do you believe in me?’ can do wonders for a kid who believes he might not have a place in the class.”

Belonging permeates Barking Abbey. Everyone refers to the “Barking Abbey family” —including the students. “Students coming in are facing terrible austerity,” said Pete Flaxman, whose title—acting deputy head teacher, inclusion, safeguarding and community—underscores the issues the school prioritizes. He also teaches geography. “Some families are terribly deprived. Those students are really cared for. School is a haven to them.”

Barking Abbey teachers understand how poverty works. They see how it grinds us and they find ways to ameliorate the pain. They understand the struggle of living in cramped, overcrowded housing, and think to provide us with classrooms to study in after school, or point us to the town’s local libraries. Where the rest of the world saw no hope for us, Maloney took us on tours to the best universities in the country.

As a refugee, the chaos in our hearts and minds doesn’t suddenly stop when our parents settle and plant roots. We have to carve out a place for ourselves with little-to-no instructions. There’s a constant battle of remembering and grieving for the world our parents left behind, helping them pick up the pieces, all whilst not being overwhelmed and washed away by our new world. It’s a juggling act, trying to find a way to straddle both histories and identities, knowing you don’t really fit in either. Barking Abbey changed the narrative by giving us a place to belong.

That has not changed today. All the teachers seem to wear multiple hats around the school. As well as teaching biology and looking after the wellbeing of 300 students, Maloney oversees a language program taught after school and works with a group of high-performing senior students—many of whom have to deal with poverty—to raise their aspirations. Over the years he has devised programs to lower teen pregnancy rates and confront tuberculosis outbreaks.

Several teachers raised concerns about gang violence. “The police are under-resourced to tackle it,” Tupman says. So, during their own time, this group of committed teachers regularly patrol local shops after school to ensure their students have gone home and are not prey to local gangs in the area.

Somehow with an ever-dwindling pool of resources, and the challenges of more diversity (never mind an ever-changing set of curriculum guidelines), Barking Abbey has created a place where students can thrive. The Barking Abbey family has changed, but it’s still a family.

Britain now faces a similar task. Leaving the EU may signal a new trade environment, or even alter the free movement of people. But for the millions of people of varying ethnicities, income brackets and religions, Brexit will not magically create a sense of belonging, or restore fractured communities. That work will fall to schools and churches, community organizers and local politicians who must lead with unwavering commitment. Jobs are essential, and the most vulnerable need to be protected. People can set their expectations high, but they also need to be prepared for honest conversations about race, and loss and identity. Gest says that there is a temptation to dismiss legitimate grievances about economic inequality and immobility as illegitimate grievances about demographic change. “Because of your cultural anxiety I will disregard your economic anxiety.” If Brexit and the election of Donald Trump has taught us anything, it’s that the two are intimately woven, and both demand attention.

“They don’t experience it on a day-to-day basis,” said Tupman, referring to Barking Abbey students’ exposure to xenophobia and racism. “When they watch the news and see that people have very different views they find it very hard.” More than one teacher noted that Trump seemed to rankle them more than Brexit.

The school’s teachers don’t downplay the enormous challenges they face—and will continue to face—integrating a radically diverse group of students, but they’re confident they can keep doing it. The students have not been shielded from the debate surrounding them; they live it, and see the many nuances to it. In many ways, they seem savvier than the politicians spewing vitriol from all sides of the political spectrum.