Luckily, the countries worst hit by the euro crisis are the least susceptible to depression and suicide

October is depression-awareness month in Europe and the press is abuzz with stories about how sad we all are. One in ten Europeans have taken time off from work for depression, according to a survey by Mori for the European Depression Association, with people from Britain, Denmark and Germany being the most likely. The association says that 11% of EU citizens suffer from depression at some point in their lives.

October is depression-awareness month in Europe and the press is abuzz with stories about how sad we all are. One in ten Europeans have taken time off from work for depression, according to a survey by Mori for the European Depression Association, with people from Britain, Denmark and Germany being the most likely. The association says that 11% of EU citizens suffer from depression at some point in their lives.

Meanwhile experts tell us what we might have already guessed: Depression is rising because of the euro crisis, just as health services to combat mental illness are being cut back.

But a closer look at the numbers reveals a more nuanced story. The Mori study shows that the British are more than twice as likely to have been diagnosed with depression as the Italians, who have been harder hit by the euro crisis. Strangely, too, workers from Germany, Denmark and Britain are more likely to take time off work because of depression than workers in France, Spain and Italy, where the impact of the crisis is most severe.

How to interpret these data? It might be that the Brits are also more willing to seek help or their doctors are better at diagnosing depression. In southern Europe people may have different cultural views on depression, or be less willing to admit problems, especially at work. (And maybe, when unemployment is as high as it is in France, Spain or Italy, people don’t dare leave their jobs, even for sickness.)

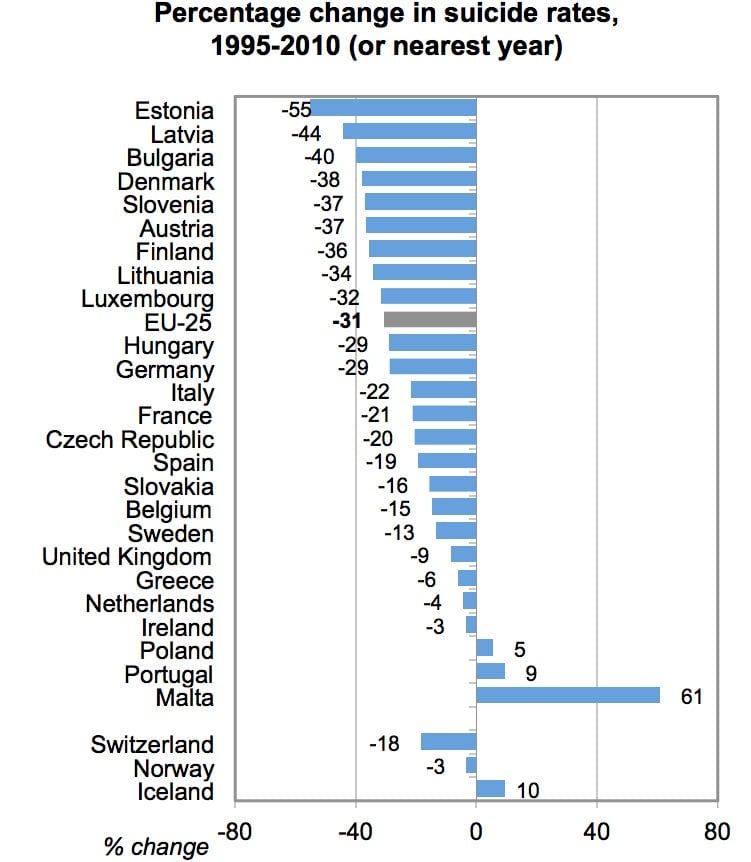

But there is a clue, perhaps, in numbers due out soon from the OECD about suicide rates. They show that rates have declined across Europe 31% between 1995 and 2010. Over the last ten years they dropped by more than 20% for 14 countries, with Estonia, Latvia and Bulgaria declining by more than 40%:

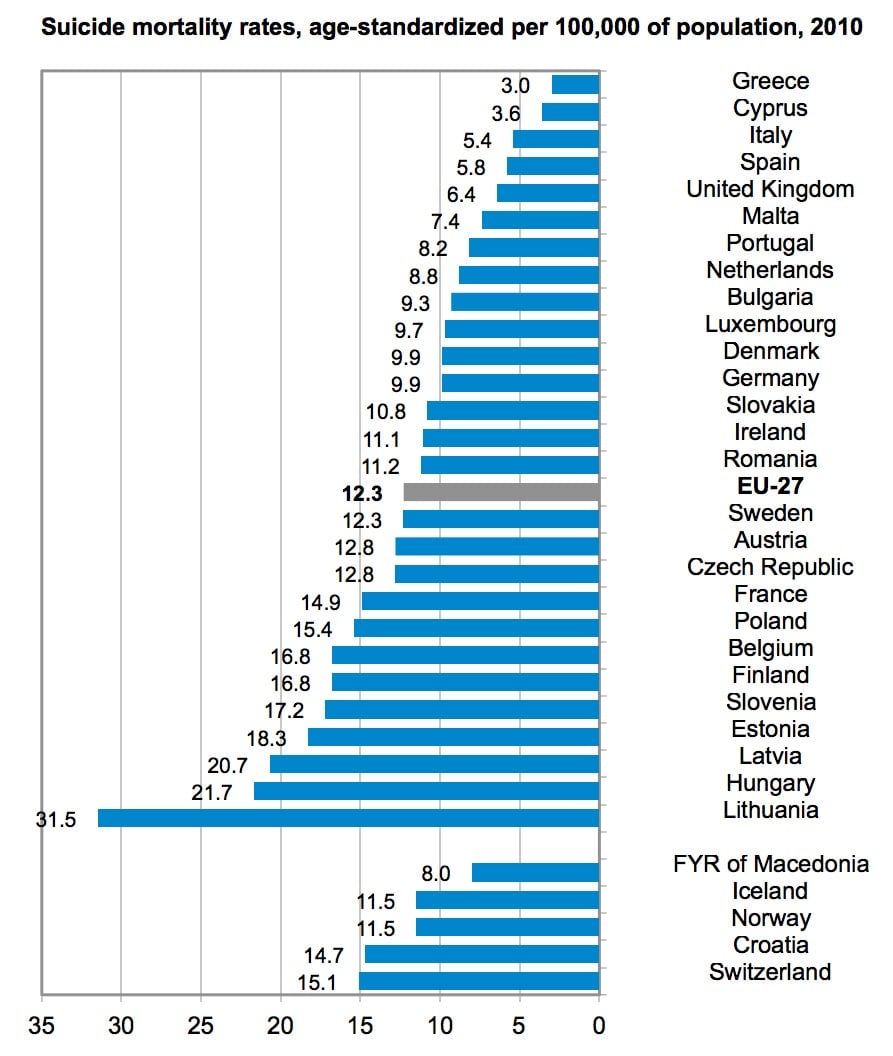

What’s more, the lowest actual suicide rates are found in the economically ravaged southern European countries: Greece, Cyprus, Italy, and Spain:

“From the evidence we have, at least on a national level, we can’t see any indication that the crisis is leading to large increases in suicide,” says Michael de Looper of the OECD. The numbers don’t cover the past year and nine months of the crisis, he adds, but even if they did they are unlikely to show big changes, particularly in Greece where the suicide rate is the lowest in Europe.