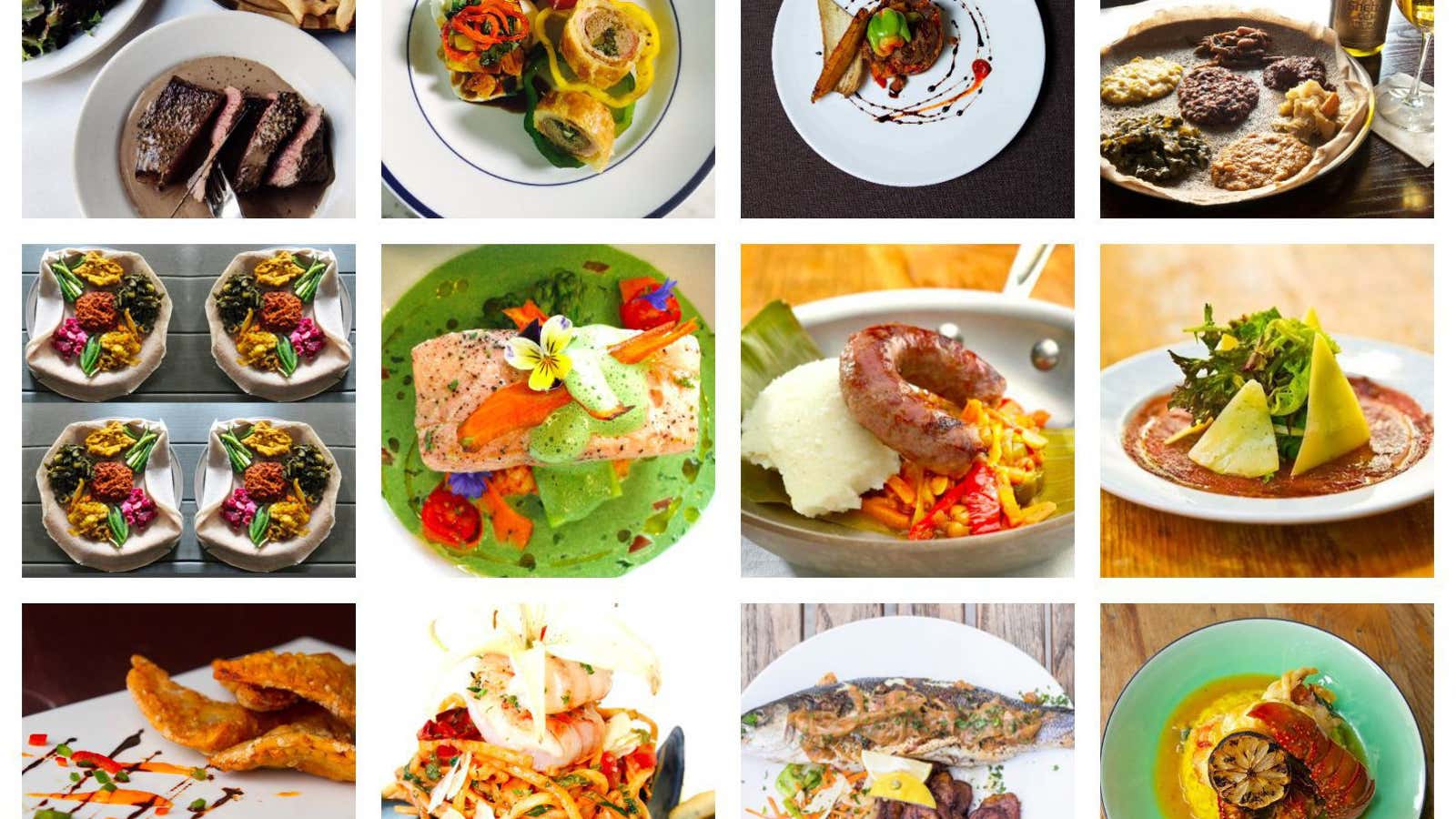

The question of which African cuisines will enter the Western mainstream is one of those debates that happens with experts looking to spot the latest global food trends.

The migration of Africans to Europe and the US has introduced a range of African products and dishes to the world. Ethiopian and Moroccan food have already made their mark with popular restaurants in urban hubs like London, New York, Paris, and Washington DC.

But the question of whether dishes from other parts of Africa can enter the mainstream depends on how that culture and country is viewed in the West, according to Krishnendu Ray, a professor of food studies at New York University. In his book, The Ethnic Restaurateur, Ray argues that assumptions about a group of people or nation can influence the popularity and pricing of their cuisine.

For African cuisines, this means overcoming assumptions about the continent and countries proving their worth as an economic and cultural force. “Our Western assessment of Chinese culture will be drifting towards the way we think of Japanese and Korean food and culture. But I haven’t seen that with Africa,” Ray said. “For the longest time, Africa was promising, Africa was rising but that hasn’t produced a major economic star. I think its foods breaking into the mainstream depends on how the economy does. This is a question of modern prejudice and a barrier for African cuisines to tackle.”

Ray believes the “Mediterranean and French connection” of Ethiopian and Moroccan food has led to them being viewed as more cosmopolitan, accessible, and sophisticated. But that’s changing. In London, one of the newest top restaurants, Ikoyi, serves West African fusion cuisine in the upmarket surroundings of St. James Park.

Street food culture

A solution to this obstacle, Ray suggests, is tapping into street food culture which has leveled up to haute cuisine as a movement in the culinary world. Akin Akinsaya, founder of New York African Restaurant Week (NYARW), saw the potential for African foods to gain attention through this model when he started the event eight years ago.

“I’ve always been proud to identify as African, but I wanted to create something to showcase what we do and give people a platform to elevate their culture,” Akinsaya said. “It became clear to me that we needed to do something for the New York African restaurants whereby we pull the restaurants together, and give New Yorkers a taste of Africa. If there’s a New York restaurant week, there has to be a week where we can showcase our own restaurants.”

The event, which takes place over three weeks in October, brings together 25 African restaurants in the city. People can sample food from vendors, receive private dining experiences with acclaimed chefs, and attend a day dedicated to educating people on foods from a certain part of the continent.

“More and more New Yorkers and restaurant owners are saying, ‘this is for us,’ or ‘we want to learn about Africa,'” Akinsaya said. He estimates that about 70% of people who attend the event are non-African.

Street food culture can be a valuable way to introduce a piece of the continent to the rest of the world. Recently, DF Nigerian, a food truck based in Manhattan’s Midtown, won The Vendy Awards, a yearly competition which selects the best food trucks in New York City. The food truck, started by Nigerian couple Godshelter and Bisola Oluwalogbon in 2015, serves popular Nigerian dishes like jollof rice, sautéed gizzards, and suya. In the same way taco and kebab food trucks are go-to food stops for people in large cities, African cuisines could benefit from the ease and convenience that this model offers.

The power of fusion

For African cuisines that aren’t well-known or don’t have a large immigration group, associations with haute cuisines can be a way to appeal to Western tastes.

“You climb the system by partly latching on to elements of the system which are on the higher end,” says Ray. “In a sense, you have to break into a domain. The way African art enters into cubism, the way Japanese water colors enters into French impressionism…you have to use the idioms of your cuisine to latch onto something that already has prestige.”

This is what Cafe Rue Dix, a restaurant in Crown Heights, Brooklyn recognizes. The restaurant, which is also participating in New York African Restaurant Week, styles itself as a French-Senegalese brassiere, offering standard French classics like steak au frites alongside dishes like thiebou jen, a national Senegalese dish consisting of stewed fish, vegetables, and rice.

Lamine Diagne and Nilea Alexander, the couple who founded the restaurant in 2013, wanted to use French food as a way to introduce customers in Brooklyn to Senegalese cooking. “We felt like so many people don’t know Senegalese food but they’re familair with French food,” Alexander said.

Cafe Rue Dix employs two chefs – one responsible for the Senegalese parts of the menu, and the other who handles the French. There are also combinations with other cuisines as seen in the serving of Senegalese spring rolls and grilled tiger shrimp tapas.

Even for restaurants who haven’t ventured into fusion properly, there’s an acknowledgement it could make customers feel more comfortable trying out African foods. Another participant in NYARW, Accra Restaurant in Harlem serves Ghanaian food along with dishes from Mali, Nigeria, and Cameroon. Abdul Abdullah, events manager for the restaurant, said his father, who started the restaurant in the Bronx 25 years ago, saw that he could lure African-Americans to his restaurant by serving soul food.

“African-American soul food was very hard to get in the Bronx. You’d have to come to Harlem. So my dad figured why not combine African food with soul food. It was a good marketing strategy because it gave African-Americans who wanted that soul food the opportunity to try African food,” Abdullah said. “We haven’t had the opportunity to combine them properly. But that’s something I’m interested in.”